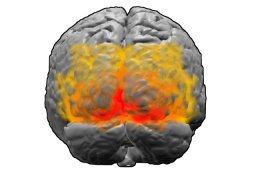

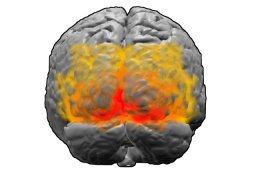

The visual cortex of the brain is the area of the cerebral cortex that processes visual information. It is located in the occipital lobe. Sensory input originating from the eyes travels through the lateral geniculate nucleus in the thalamus and then reaches the visual cortex. The area of the visual cortex that receives the sensory input from the lateral geniculate nucleus is the primary visual cortex, also known as visual area 1 (V1), Brodmann area 17, or the striate cortex. The extrastriate areas consist of visual areas 2, 3, 4, and 5.

An illusion is a distortion of the senses, which can reveal how the mind normally organizes and interprets sensory stimulation. Although illusions distort the human perception of reality, they are generally shared by most people.

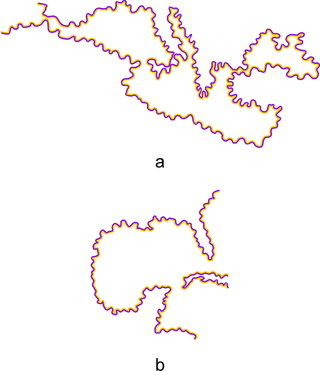

In visual perception, an optical illusion is an illusion caused by the visual system and characterized by a visual percept that arguably appears to differ from reality. Illusions come in a wide variety; their categorization is difficult because the underlying cause is often not clear but a classification proposed by Richard Gregory is useful as an orientation. According to that, there are three main classes: physical, physiological, and cognitive illusions, and in each class there are four kinds: Ambiguities, distortions, paradoxes, and fictions. A classical example for a physical distortion would be the apparent bending of a stick half immerged in water; an example for a physiological paradox is the motion aftereffect. An example for a physiological fiction is an afterimage. Three typical cognitive distortions are the Ponzo, Poggendorff, and Müller-Lyer illusion. Physical illusions are caused by the physical environment, e.g. by the optical properties of water. Physiological illusions arise in the eye or the visual pathway, e.g. from the effects of excessive stimulation of a specific receptor type. Cognitive visual illusions are the result of unconscious inferences and are perhaps those most widely known.

Gestalt psychology, gestaltism, or configurationism is a school of psychology and a theory of perception that emphasises the processing of entire patterns and configurations, and not merely individual components. It emerged in the early twentieth century in Austria and Germany as a rejection of basic principles of Wilhelm Wundt's and Edward Titchener's elementalist and structuralist psychology.

The term phi phenomenon is used in a narrow sense for an apparent motion that is observed if two nearby optical stimuli are presented in alternation with a relatively high frequency. In contrast to beta movement, seen at lower frequencies, the stimuli themselves do not appear to move. Instead, a diffuse, amorphous shadowlike something seems to jump in front of the stimuli and occlude them temporarily. This shadow seems to have nearly the color of the background. Max Wertheimer first described this form of apparent movement in his habilitation thesis, published 1912, marking the birth of Gestalt psychology.

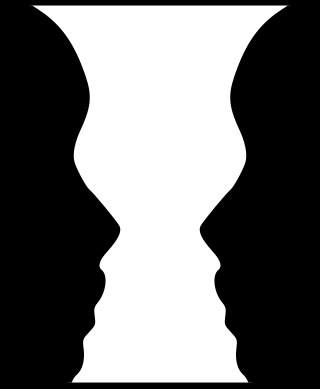

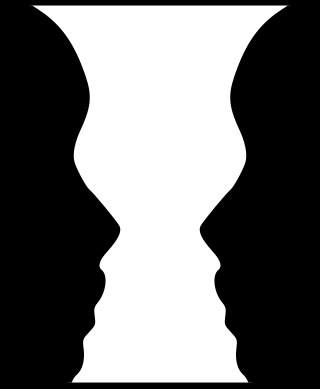

Figure–ground organization is a type of perceptual grouping that is a vital necessity for recognizing objects through vision. In Gestalt psychology it is known as identifying a figure from the background. For example, black words on a printed paper are seen as the "figure", and the white sheet as the "background".

Ambiguous images or reversible figures are visual forms that create ambiguity by exploiting graphical similarities and other properties of visual system interpretation between two or more distinct image forms. These are famous for inducing the phenomenon of multistable perception. Multistable perception is the occurrence of an image being able to provide multiple, although stable, perceptions.

The McCollough effect is a phenomenon of human visual perception in which colorless gratings appear colored contingent on the orientation of the gratings. It is an aftereffect requiring a period of induction to produce it. For example, if someone alternately looks at a red horizontal grating and a green vertical grating for a few minutes, a black-and-white horizontal grating will then look greenish and a black-and-white vertical grating will then look pinkish. The effect is remarkable because, although it diminishes rapidly with repeated testing, it has been reported to last up to 2.8 months when exposure to testing is limited.

Amodal perception is the perception of the whole of a physical structure when only parts of it affect the sensory receptors. For example, a table will be perceived as a complete volumetric structure even if only part of it—the facing surface—projects to the retina; it is perceived as possessing internal volume and hidden rear surfaces despite the fact that only the near surfaces are exposed to view. Similarly, the world around us is perceived as a surrounding plenum, even though only part of it is in view at any time. Another much quoted example is that of the "dog behind a picket fence" in which a long narrow object is partially occluded by fence-posts in front of it, but is nevertheless perceived as a single continuous object. Albert Bregman noted an auditory analogue of this phenomenon: when a melody is interrupted by bursts of white noise, it is nonetheless heard as a single melody continuing "behind" the bursts of noise.

The Ehrenstein illusion is an optical illusion of brightness or color perception. The visual phenomena was studied by the German psychologist Walter H. Ehrenstein (1899–1961) who originally wanted to modify the theory behind the Hermann grid illusion. In the discovery of the optical illusion, Ehrenstein found that grating patterns of straight lines that stop at a certain point appear to have a brighter centre, compared to the background.

In human perception, contingent aftereffects are illusory percepts that are apparent on a test stimulus after exposure to an induction stimulus for an extended period. Contingent aftereffects can be contrasted with simple aftereffects, the latter requiring no test stimulus for the illusion/mis-perception to be apparent. Contingent aftereffects have been studied in different perceptual domains. For instance, visual contingent aftereffects, auditory contingent aftereffects and haptic contingent aftereffects have all been discovered.

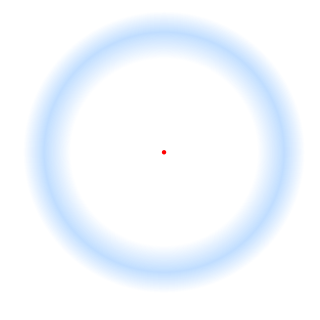

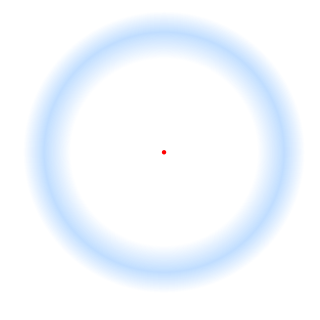

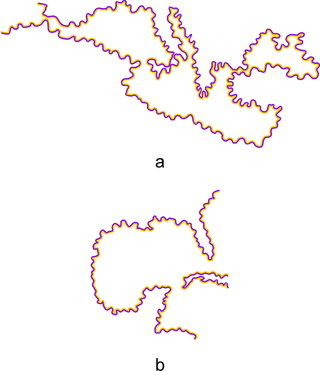

In vision, filling-in phenomena are those responsible for the completion of missing information across the physiological blind spot, and across natural and artificial scotomata. There is also evidence for similar mechanisms of completion in normal visual analysis. Classical demonstrations of perceptual filling-in involve filling in at the blind spot in monocular vision, and images stabilized on the retina either by means of special lenses, or under certain conditions of steady fixation. For example, naturally in monocular vision at the physiological blind spot, the percept is not a hole in the visual field, but the content is “filled-in” based on information from the surrounding visual field. When a textured stimulus is presented centered on but extending beyond the region of the blind spot, a continuous texture is perceived. This partially inferred percept is paradoxically considered more reliable than a percept based on external input..

The Chubb illusion is an optical illusion or error in visual perception in which the apparent contrast of an object varies substantially to most viewers depending on its relative contrast to the field on which it is displayed. These visual illusions are of particular interest to researchers because they may provide valuable insights in regard to the workings of human visual systems.

Stuart M. Anstis is a professor emeritus of psychology at the University of California, San Diego, in the United States.

The watercolor illusion, also referred to as the water-color effect, is an optical illusion in which a white area takes on a pale tint of a thin, bright, intensely colored polygon surrounding it if the coloured polygon is itself surrounded by a thin, darker border. The inner and outer borders of watercolor illusion objects often are of complementary colours. The watercolor illusion is best when the inner and outer contours have chromaticities in opposite directions in color space. The most common complementary pair is orange and purple. The watercolor illusion is dependent on the combination of luminance and color contrast of the contour lines in order to have the color spreading effect occur.

Neon color spreading is an optical illusion in the category of transparency effects, characterized by fluid borders between the edges of a colored object and the background in the presence of black lines. The illusion was first documented in 1971 and was eventually rediscovered in 1975 by Van Tuijl.

Geometrical–optical are visual illusions, also optical illusions, in which the geometrical properties of what is seen differ from those of the corresponding objects in the visual field.

A phantom contour is a type of illusory contour. Most illusory contours are seen in still images, such as the Kanizsa triangle and the Ehrenstein illusion. A phantom contour, however, is perceived in the presence of moving or flickering images with contrast reversal. The rapid, continuous alternation between opposing, but correlated, adjacent images creates the perception of a contour that is not physically present in the still images. Quaid et al. have also authored a PhD thesis on the phantom contour illusion and its spatiotemporal limits which maps out limits and proposes mechanisms for its perception centering around magnocellularly driven visual area MT.

Due to the effect of a spatial context or temporal context, the perceived orientation of a test line or grating pattern can appear tilted away from its physical orientation. The tilt illusion (TI) is the phenomenon that the perceived orientation of a test line or grating is altered by the presence of surrounding lines or grating with a different orientation. And the tilt aftereffect (TAE) is the phenomenon that the perceived orientation is changed after prolonged inspection of another oriented line or grating.

Amodal completion is the ability to see an entire object despite parts of it being covered by another object in front of it. It is one of the many functions of the visual system which aid in both seeing and understanding objects encountered on an everyday basis. This mechanism allows the world to be perceived as though it is made of coherent wholes. For example, when the sun sets over the horizon it is still perceived as a full circle, despite occlusion causing it to appear as a semi-circle. Another example of this is a cat behind a picket fence. Amodal completion allows the cats to be seen as a full animal continuing behind each picket of the fence. Essentially amodal completion allows for sensory stimulation from any parts of an occluded object we can not directly see.