Edmund I or Eadmund I was King of the English from 27 October 939 until his death. He was the elder son of King Edward the Elder and his third wife, Queen Eadgifu, and a grandson of King Alfred the Great. After Edward died in 924, he was succeeded by his eldest son, Edmund's half-brother Æthelstan. Edmund was crowned after Æthelstan died childless in 939. He had two sons, Eadwig and Edgar, by his first wife Ælfgifu, and none by his second wife Æthelflæd. His sons were young children when he was killed in a brawl with an outlaw at Pucklechurch in Gloucestershire, and he was succeeded by his younger brother Eadred, who died in 955 and was followed by Edmund's sons in succession.

Justus was the fourth Archbishop of Canterbury. He was sent from Italy to England by Pope Gregory the Great, on a mission to Christianize the Anglo-Saxons from their native paganism, probably arriving with the second group of missionaries despatched in 601. Justus became the first Bishop of Rochester in 604, and attended a church council in Paris in 614.

Edward, often called the Martyr, was King of the English from 975 until he was murdered in 978. Edward was the eldest son of King Edgar, but was not his father's acknowledged heir. On Edgar's death, the leadership of England was contested, with some supporting Edward's claim to be king and others supporting his younger half-brother Æthelred, recognised as a legitimate son of Edgar. Edward was chosen as king and was crowned by his main clerical supporters, the archbishops Dunstan of Canterbury and Oswald of York.

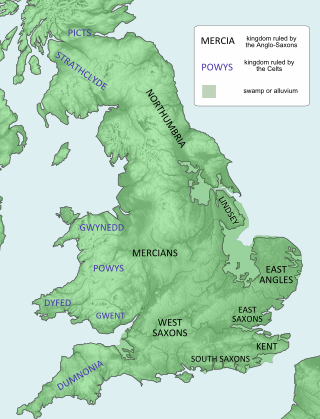

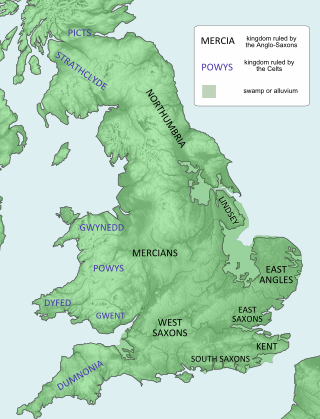

Æthelflæd, Lady of the Mercians ruled Mercia in the English Midlands from 911 until her death. She was the eldest daughter of Alfred the Great, king of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Wessex, and his wife Ealhswith.

Ecgberht, also spelled Egbert, Ecgbert, Ecgbriht, Ecgbeorht, and Ecbert, was King of Wessex from 802 until his death in 839. His father was King Ealhmund of Kent. In the 780s, Ecgberht was forced into exile to Charlemagne's court in the Frankish Empire by the kings Offa of Mercia and Beorhtric of Wessex, but on Beorhtric's death in 802, Ecgberht returned and took the throne.

Eadred was King of the English from 26 May 946 until his death. He was the younger son of Edward the Elder and his third wife Eadgifu, and a grandson of Alfred the Great. His elder brother, Edmund, was killed trying to protect his seneschal from an attack by a violent thief. Edmund's two sons, Eadwig and Edgar, were then young children, so Eadred became king. He suffered from ill health in the last years of his life and he died at the age of a little over thirty, having never married. He was succeeded successively by his nephews, Eadwig and Edgar.

A Marcher lord was a noble appointed by the king of England to guard the border between England and Wales.

In later Anglo-Saxon England, 10th to 11th centuries, a thegn or thane was an aristocrat who owned substantial land in one or more counties. Thanes ranked at the third level in lay society, below the king and ealdormen. Thanage refers to the tenure by which lands were held by a thane as well as the rank.

Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians became ruler of English Mercia shortly after the death or disappearance of its last king, Ceolwulf II in 879. Æthelred's rule was confined to the western half, as eastern Mercia was then part of the Viking-ruled Danelaw. His ancestry is unknown. He was probably the leader of an unsuccessful Mercian invasion of Wales in 881, and soon afterwards he acknowledged the lordship of King Alfred the Great of Wessex. This alliance was cemented by the marriage of Æthelred to Alfred's daughter Æthelflæd.

Coenred was king of Mercia from 704 to 709. Mercia was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom in the English Midlands. He was a son of the Mercian king Wulfhere, whose brother Æthelred succeeded to the throne in 675 on Wulfhere's death. In 704, Æthelred abdicated in favour of Coenred to become a monk.

The term soke, at the time of the Norman conquest of England, generally denoted "jurisdiction", but its vague usage makes it probably lack a single, precise definition.

Anglo-Saxon law is a body of written rules and customs that were in place during the Anglo-Saxon period in England, before the Norman conquest. This body of law, along with early Medieval Scandinavian law and Germanic law, descended from a family of ancient Germanic custom and legal thought. However, Anglo-Saxon law codes are distinct from other early Germanic legal statements—known as the leges barbarorum, in part because they were written in Old English instead of in Latin. The laws of the Anglo-Saxons were the second in medieval Western Europe after those of the Irish to be expressed in a language other than Latin.

Henry of Bracton, also Henry de Bracton, also Henricus Bracton, or Henry Bratton also Henry Bretton was an English cleric and jurist.

Quia Emptores is a statute passed by the Parliament of England in 1290 during the reign of Edward I that prevented tenants from alienating their lands to others by subinfeudation, instead requiring all tenants who wished to alienate their land to do so by substitution. The statute, along with its companion statute Quo Warranto also passed in 1290, was intended to remedy land ownership disputes and consequent financial difficulties that had resulted from the decline of the traditional feudal system in England during the High Middle Ages. The name Quia Emptores derives from the first two words of the statute in its original mediaeval Latin, which can be translated as "because the buyers". Its long title is A Statute of our Lord The King, concerning the Selling and Buying of Land. It is also cited as the Statute of Westminster III, one of many English and British statutes with that title.

Berhtwald was the ninth Archbishop of Canterbury in England. Documentary evidence names Berhtwald as abbot at Reculver before his election as archbishop. Berhtwald begins the first continuous series of native-born Archbishops of Canterbury, although there had been previous Anglo-Saxon archbishops, they had not succeeded each other until Berhtwald's reign.

The Councils of Clovesho or Clofesho were a series of synods attended by Anglo-Saxon kings, bishops, abbots and nobles in the 8th and 9th centuries. They took place at an unknown location in the Kingdom of Mercia.

The ancient boroughs were a historic unit of lower-tier local government in England and Wales. The ancient boroughs covered only important towns and were established by charters granted at different times by the monarchy. Their history is largely concerned with the origin of such towns and how they gained the right of self-government. Ancient boroughs were reformed by the Municipal Corporations Act 1835, which introduced directly elected corporations and allowed the incorporation of new industrial towns. Municipal boroughs ceased to be used for the purposes of local government in 1974, with borough status retained as an honorific title granted to some post-1974 local government districts by the Crown.

In Anglo-Saxon law, backberend and handhabend were terms applied to a thief who was found having the stolen goods in his possession. The terms are respectively derived from "bearing [a thing] upon the back" and "having [a thing] in the hand".

Toll and team were related privileges granted by the Crown to landowners under Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman law. First known from a charter of around 1023, the privileges usually appeared as part of a standard formula in charters granting privileges to estate-holders, along the lines of "with sac and soc, toll and team, infangthief and outfangthief" and so on.

Waif and stray was a legal privilege commonly granted by the Crown to landowners under Anglo-Norman law. It usually appeared as part of a standard formula in charters granting privileges to estate-holders, along the lines of "with sac and soc, toll and team, infangthief and outfangthief" and so on.