Computer security is the protection of computer software, systems and networks from threats that may result in unauthorized information disclosure, theft of hardware, software, or data, as well as from the disruption or misdirection of the services they provide.

Cyberterrorism is the use of the Internet to conduct violent acts that result in, or threaten, the loss of life or significant bodily harm, in order to achieve political or ideological gains through threat or intimidation. Emerging alongside the development of information technology, cyberterrorism involves acts of deliberate, large-scale disruption of computer networks, especially of personal computers attached to the Internet by means of tools such as computer viruses, computer worms, phishing, malicious software, hardware methods, and programming scripts can all be forms of internet terrorism. Some authors opt for a very narrow definition of cyberterrorism, relating to deployment by known terrorist organizations of disruption attacks against information systems for the primary purpose of creating alarm, panic, or physical disruption. Other authors prefer a broader definition, which includes cybercrime. Participating in a cyberattack affects the terror threat perception, even if it isn't done with a violent approach. By some definitions, it might be difficult to distinguish which instances of online activities are cyberterrorism or cybercrime.

A cybersecurity regulation comprises directives that safeguard information technology and computer systems with the purpose of forcing companies and organizations to protect their systems and information from cyberattacks like viruses, worms, Trojan horses, phishing, denial of service (DOS) attacks, unauthorized access and control system attacks. While cybersecurity regulations aim to minimize cyber risks and enhance protection, the uncertainty arising from frequent changes or new regulations can significantly impact organizational response strategies.

Shadowserver Foundation is a nonprofit security organization that gathers and analyzes data on malicious Internet activity, sends daily network reports to subscribers, and works with law enforcement organizations around the world in cybercrime investigations. Established in 2004 as a "volunteer watchdog group," it liaises with national governments, CSIRTs, network providers, academic institutions, financial institutions, Fortune 500 companies, and end users to improve Internet security, enhance product capability, advance research, and dismantle criminal infrastructure. Shadowserver provides its data at no cost to national CSIRTs and network owners.

Anonymous is a decentralized international activist and hacktivist collective and movement primarily known for its various cyberattacks against several governments, government institutions and government agencies, corporations and the Church of Scientology.

A supply chain attack is a cyber-attack that seeks to damage an organization by targeting less secure elements in the supply chain. A supply chain attack can occur in any industry, from the financial sector, oil industry, to a government sector. A supply chain attack can happen in software or hardware. Cybercriminals typically tamper with the manufacturing or distribution of a product by installing malware or hardware-based spying components. Symantec's 2019 Internet Security Threat Report states that supply chain attacks increased by 78 percent in 2018.

Cyberwarfare is the use of computer technology to disrupt the activities of a state or organization, especially the deliberate attacking of information systems for strategic or military purposes. As a major developed economy, the United States is highly dependent on the Internet and therefore greatly exposed to cyber attacks. At the same time, the United States has substantial capabilities in both defense and power projection thanks to comparatively advanced technology and a large military budget. Cyber warfare presents a growing threat to physical systems and infrastructures that are linked to the internet. Malicious hacking from domestic or foreign enemies remains a constant threat to the United States. In response to these growing threats, the United States has developed significant cyber capabilities.

LulzSec was a black hat computer hacking group that claimed responsibility for several high profile attacks, including the compromise of user accounts from PlayStation Network in 2011. The group also claimed responsibility for taking the CIA website offline. Some security professionals have commented that LulzSec has drawn attention to insecure systems and the dangers of password reuse. It has gained attention due to its high profile targets and the sarcastic messages it has posted in the aftermath of its attacks. One of the founders of LulzSec was computer security specialist Hector Monsegur, who used the online moniker Sabu. He later helped law enforcement track down other members of the organization as part of a plea deal. At least four associates of LulzSec were arrested in March 2012 as part of this investigation. Prior, British authorities had announced the arrests of two teenagers they alleged were LulzSec members, going by the pseudonyms T-flow and Topiary.

Operation Anti-Security, also referred to as Operation AntiSec or #AntiSec, is a series of hacking attacks performed by members of the hacking group LulzSec and Anonymous, and others inspired by the announcement of the operation. LulzSec performed the earliest attacks of the operation, with the first against the Serious Organised Crime Agency on 20 June 2011. Soon after, the group released information taken from the servers of the Arizona Department of Public Safety; Anonymous would later release information from the same agency two more times. An offshoot of the group calling themselves LulzSecBrazil launched attacks on numerous websites belonging to the Government of Brazil and the energy company Petrobras. LulzSec claimed to retire as a group, but on 18 July they reconvened to hack into the websites of British newspapers The Sun and The Times, posting a fake news story of the death of the publication's owner Rupert Murdoch.

The Criminal, Cyber, Response, and Services Branch (CCRSB) is a service within the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). The CCRSB is responsible for investigating financial crime, white-collar crime, violent crime, organized crime, public corruption, violations of individual civil rights, and drug-related crime. In addition, the Branch also oversees all computer-based crime related to counterterrorism, counterintelligence, and criminal threats against the United States.

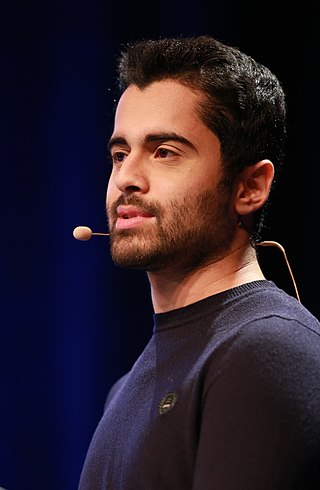

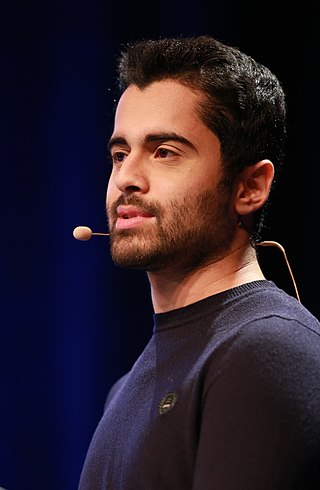

Mustafa Al-Bassam is an Iraqi- British computer security researcher, hacker, and co-founder of Celestia Labs. Al-Bassam co-founded the hacker group LulzSec in 2011, which was responsible for several high profile breaches. He later went on to co-found Chainspace, a company implementing a smart contract platform, which was acquired by Facebook in 2019. In 2021, Al-Bassam graduated from University College London, completing a PhD in computer science with a thesis on Securely Scaling Blockchain Base Layers. In 2016, Forbes listed Al-Bassam as one of the 30 Under 30 entrepreneurs in technology.

Ryan Ackroyd, a.k.a.Kayla and also lolspoon, is a former black hat hacker who was one of the six core members of the computer hacking group "LulzSec" during its 50-day spree of attacks from 6 May 2011 until 26 June 2011. Throughout the time, Ackroyd posed as a female hacker named "Kayla" and was responsible for the penetration of multiple military and government domains and many high profile intrusions into the networks of Gawker in December 2010, HBGaryFederal in 2011, PBS, Sony, Infragard Atlanta, Fox Entertainment and others. He eventually served 30 months in prison for his hacking activities.

dark0de, also known as Darkode, is a cybercrime forum and black marketplace described by Europol as "the most prolific English-speaking cybercriminal forum to date". The site, which was launched in 2007, serves as a venue for the sale and trade of hacking services, botnets, malware, stolen personally identifiable information, credit card information, hacked server credentials, and other illicit goods and services.

The Center for Internet Security (CIS) is a US 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, formed in October 2000. Its mission statement professes that the function of CIS is to " help people, businesses, and governments protect themselves against pervasive cyber threats."

Phyllis Schneck is an American executive and cybersecurity professional. As of May 2017, she became the managing director at Promontory Financial Group. Schneck served in the Obama administration as Deputy Under Secretary for Cybersecurity and Communications for the National Protection and Programs Directorate (NPPD), at the Department of Homeland Security.

Hack Forums is an Internet forum dedicated to discussions related to hacker culture and computer security. The website ranks as the number one website in the "Hacking" category in terms of web-traffic by the analysis company Alexa Internet. The website has been widely reported as facilitating online criminal activity, such as the case of Zachary Shames, who was arrested for selling keylogging software on Hack Forums in 2013 which was used to steal personal information.

Operational collaboration is a cyber resilience framework that leverages public-private partnerships to reduce the risk of cyber threats and the impact of cyberattacks on United States cyberspace. This operational collaboration framework for cyber is similar to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)'s National Preparedness System which is used to coordinate responses to natural disasters, terrorism, chemical and biological events in the physical world.

On November 13, 2021, a hacker named Conor Brian Fitzpatrick, going by his alias "Pompompurin", compromised the FBI's external email system, sending thousands of messages warning of a cyberattack by cybersecurity CEO Vinny Troia who was falsely suggested to have been identified as part of The Dark Overlord hacking group by the United States Department of Homeland Security.

BreachForums, sometimes referred to as Breached, is an English-language black hat–hacking crime forum. The website acted as an alternative and successor to RaidForums following its shutdown and seizure in 2022. Like its predecessor, BreachForums allows for the discussion of various hacking topics and distributed data breaches, pornography, hacking tools and various other services.

Once a cyberattack has been initiated, certain targets need to be attacked to cripple the opponent. Certain infrastructures as targets have been highlighted as critical infrastructures in times of conflict that can severely cripple a nation. Control systems, energy resources, finance, telecommunications, transportation, and water facilities are seen as critical infrastructure targets during conflict. A new report on the industrial cybersecurity problems, produced by the British Columbia Institute of Technology, and the PA Consulting Group, using data from as far back as 1981, reportedly has found a 10-fold increase in the number of successful cyber attacks on infrastructure Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems since 2000. Cyberattacks that have an adverse physical effect are known as cyber-physical attacks.