Related Research Articles

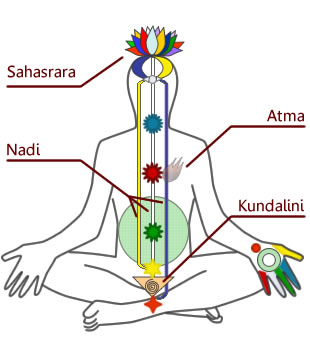

In Hinduism, kundalini is a form of divine feminine energy believed to be located at the base of the spine, in the muladhara. It is an important concept in Śhaiva Tantra, where it is believed to be a force or power associated with the divine feminine or the formless aspect of the Goddess. This energy in the body, when cultivated and awakened through tantric practice, is believed to lead to spiritual liberation. Kuṇḍalinī is associated with the goddess Parvati or Adi Parashakti, the supreme being in Shaktism, and with the goddesses Bhairavi and Kubjika. The term, along with practices associated with it, was adopted into Hatha Yoga in the 9th century. It has since then been adopted into other forms of Hinduism as well as modern spirituality and New Age thought.

Barbara McClintock was an American scientist and cytogeneticist who was awarded the 1983 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. McClintock received her PhD in botany from Cornell University in 1927. There she started her career as the leader of the development of maize cytogenetics, the focus of her research for the rest of her life. From the late 1920s, McClintock studied chromosomes and how they change during reproduction in maize. She developed the technique for visualizing maize chromosomes and used microscopic analysis to demonstrate many fundamental genetic ideas. One of those ideas was the notion of genetic recombination by crossing-over during meiosis—a mechanism by which chromosomes exchange information. She produced the first genetic map for maize, linking regions of the chromosome to physical traits. She demonstrated the role of the telomere and centromere, regions of the chromosome that are important in the conservation of genetic information. She was recognized as among the best in the field, awarded prestigious fellowships, and elected a member of the National Academy of Sciences in 1944.

Eugene Gladstone O'Neill was an American playwright. His poetically titled plays were among the first to introduce into the U.S. the drama techniques of realism, earlier associated with Chekhov, Ibsen, and Strindberg. The tragedy Long Day's Journey into Night is often included on lists of the finest U.S. plays in the 20th century, alongside Tennessee Williams's A Streetcar Named Desire and Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman. He was awarded the 1936 Nobel Prize in Literature. O'Neill is also the only playwright to win four Pulitzer Prizes for Drama.

Knowledge is a term used by Shri Hans Ji Maharaj to denote a formulation of four specific techniques that were imparted in a process of initiation. The term continues to be used by two of Shri Hans Ji Maharaj's sons, Satpal Rawat and Prem Rawat.

Psychosynthesis is an approach to psychology that expands the boundaries of the field by identifying a deeper center of identity, which is the postulate of the Self. It considers each individual unique in terms of purpose in life, and places value on the exploration of human potential. The approach combines spiritual development with psychological healing by including the life journey of an individual or their unique path to self-realization.

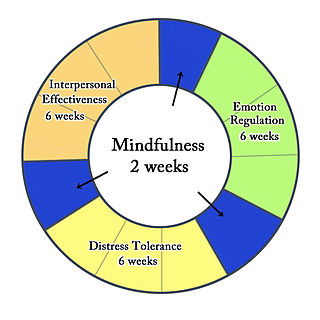

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) is an evidence-based psychotherapy that began with efforts to treat personality disorders and interpersonal conflicts. Evidence suggests that DBT can be useful in treating mood disorders and suicidal ideation as well as for changing behavioral patterns such as self-harm and substance use. DBT evolved into a process in which the therapist and client work with acceptance and change-oriented strategies and ultimately balance and synthesize them—comparable to the philosophical dialectical process of thesis and antithesis, followed by synthesis.

Gestalt therapy is a form of psychotherapy that emphasizes personal responsibility and focuses on the individual's experience in the present moment, the therapist–client relationship, the environmental and social contexts of a person's life, and the self-regulating adjustments people make as a result of their overall situation. It was developed by Fritz Perls, Laura Perls and Paul Goodman in the 1940s and 1950s, and was first described in the 1951 book Gestalt Therapy.

Process-oriented psychology, also called process work, is a depth psychology theory and set of techniques developed by Arnold Mindell and associated with transpersonal psychology, somatic psychology and post-Jungian psychology. Process oriented psychology has been applied in contexts including individual therapy and working with groups and organisations. It is known for extending dream analysis to body experiences and for applying psychology to world issues including socioeconomic disparities, diversity issues, social conflict and leadership.

Focusing is an internally oriented psychotherapeutic process developed by psychotherapist Eugene Gendlin. It can be used in any kind of therapeutic situation, including peer-to-peer sessions. It involves holding a specific kind of open, non-judging attention to an internal knowing which is experienced but is not yet in words. Focusing can, among other things, be used to become clear on what one feels or wants, to obtain new insights about one's situation, and to stimulate change or healing of the situation. Focusing is set apart from other methods of inner awareness by three qualities: something called the "felt sense", a quality of engaged accepting attention, and a research-based technique that facilitates change.

Eugene Tovio Gendlin was an American philosopher who developed ways of thinking about and working with living process, the bodily felt sense and the "philosophy of the implicit". Though he had no degree in the field of psychology, his advanced study with Carl Rogers, his longtime practice of psychotherapy and his extensive writings in the field of psychology have made him perhaps better known in that field than in philosophy. He studied under Carl Rogers, the founder of client-centered therapy, at the University of Chicago and received his PhD in philosophy in 1958. Gendlin's theories impacted Rogers' own beliefs and played a role in Rogers' view of psychotherapy. From 1958 to 1963 Gendlin was Research Director at the Wisconsin Psychiatric Institute of the University of Wisconsin. He served as an associate professor in the departments of Philosophy and Comparative Human Development at the University of Chicago from 1964 until 1995.

Behaviour therapy or behavioural psychotherapy is a broad term referring to clinical psychotherapy that uses techniques derived from behaviourism and/or cognitive psychology. It looks at specific, learned behaviours and how the environment, or other people's mental states, influences those behaviours, and consists of techniques based on behaviorism's theory of learning: respondent or operant conditioning. Behaviourists who practice these techniques are either behaviour analysts or cognitive-behavioural therapists. They tend to look for treatment outcomes that are objectively measurable. Behaviour therapy does not involve one specific method, but it has a wide range of techniques that can be used to treat a person's psychological problems.

Stephen Edred Flowers, commonly known as Stephen E. Flowers or his pen name Edred Thorsson, is an American runologist, university lecturer, and proponent of occultism, especially of Neo-Germanic paganism and Odinism. He helped establish the Germanic Neopagan movement in North America and has also been active in left-hand path occult organizations. He has over three dozen published books and hundreds of published papers and translations on a disparate range of subjects. Flowers has worked to promote the European New Right.

Hariwansh Lal Poonja was an Indian sage. Poonja was called "Poonjaji" or "Papaji" by devotees. He was a key figure in the Neo-Advaita movement.

Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon was an English educationalist and artist, a philanthropist, and a leading mid-19th-century feminist and women's rights activist. She published her influential Brief Summary of the Laws of England concerning Women in 1854 and the English Woman's Journal in 1858. Bodichon co-founded Girton College, Cambridge (1869). Her brother was the Arctic explorer Benjamin Leigh Smith.

Emotionally focused therapy and emotion-focused therapy (EFT) are related humanistic approaches to psychotherapy that aim to resolve emotional and relationship issues with individuals, couples, and families. These therapies combine experiential therapy techniques, including person-centered and Gestalt therapies, with systemic therapy and attachment theory. The central premise is that emotions influence cognition, motivate behavior, and are strongly linked to needs. The goals of treatment include transforming maladaptive behaviors, such as emotional avoidance, and developing awareness, acceptance, expression, and regulation of emotion and understanding of relationships. EFT is usually a short-term treatment.

The inner critic or critical inner voice is a concept used in popular psychology and psychotherapy to refer to a subpersonality that judges and demeans a person.

Ann Weiser Cornell is an American author, educator, and worldwide authority on Focusing, the self-inquiry psychotherapeutic technique developed by Eugene Gendlin. She has written several definitive books on Focusing, including The Power of Focusing: A Practical Guide to Emotional Self-Healing, The Focusing Student's and Companion's Manual, and Focusing in Clinical Practice. Cornell has taught Focusing around the world since 1980, and has developed a system and technique called Inner Relationship Focusing. She is also a past president of the Association for Humanistic Psychology.

Susan Margaret Watkins is a Cornell University professor emerita who founded the academic field of functional apparel design. She is the author of the seminal textbook in the field, Clothing: The Portable Environment (1984), and holds patents as a result of her collaborative research with the U.S. Army, the U.S. Air Force, firefighters associations, and other industrial partners. In 1991 Watkins was inducted as a Fellow into the International Textile and Apparel Association (ITAA), the highest honor awarded by the organization, for her contributions in shaping the field of functional apparel design.

The Shandilya Upanishad is a Sanskrit text and one of the minor Upanishads of Hinduism. It is one of twenty Yoga Upanishads in the four Vedas, and is attached to the Atharvaveda.

Adi Da Samraj was an American-born spiritual teacher, writer and artist. He was the founder of a new religious movement known as Adidam.

References

- 1 2 Wehrenberg, Margaret. The 10 Best-Ever Anxiety Management Techniques: Understanding How Your Brain Makes You Anxious and What You Can Do to Change It. W. W. Norton & Company, 2010. p. 149.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Cornell, Ann Weiser and Barbara McGavin. "Inner Relationship Focusing". Focusing Folio. Volume 21, Number 1, 2008. pp. 21–33.

- ↑ Cornell, Ann Weiser. Focusing in Clinical Practice: The Essence of Change. W. W. Norton & Company, 2013. p. xxxi.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kirschner, Ellen. "FOCUS ON: Ann Weiser Cornell". Staying in Focus: The Focusing Institute Newsletter. Vol. IV, No. 2. May 2004.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cornell, Ann Weiser. "The Origins and Development of Inner Relationship Focusing". In: Cornell, Ann Weiser and Barbara McGavin. The Radical Acceptance of Everything: Living a Focusing Life. Calluna Press, 2005. pp. 193 ff.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Van Nuys, David. "Focusing with Ann Weiser Cornell". Shrink Rap. July 30, 2009.

- ↑ McGavin, Barbara. "The ‘Victim’, the ‘Critic’ and the Inner Relationship: Focusing with the Part that Wants to Die". The Focusing Connection. September 1994.

- 1 2 Cornell, Ann Weiser and Barbara McGavin. "A Brief History of Inner Relationship Focusing". In: The Focusing Student's and Companion's Manual, Volume 1 . Calluna Press, 2002. p. ii.

- ↑ Cornell, Ann Weiser. The Focusing Guide's Manual. Focusing Resources, 1993.

- ↑ Cornell, Ann Weiser. The Focusing Student's Manual. Focusing Resources, 1994.

- ↑ Gendlin, Eugene. Advance praise for The Radical Acceptance of Everything. 2005. "Ann Weiser Cornell has been teaching for many years in many countries and is well known worldwide. In her previous book and her manuals she has created new specific and accessible instructions for focusing as well as for the teachers of focusing. In person and through her students and writings she has given Focusing to far more people than any other single individual. She is a powerful force in making the world better. She has gone on to create different new processes in new dimensions ...." – Eugene Gendlin, author of Focusing.

- ↑ Gendlin, Eugene. Review of Focusing in Clinical Practice: The Essence of Change. W. W. Norton & Company, 2013. "Ann Weiser Cornell and I have been working closely together for thirty years, and she knows as much about Focusing as I do. Ann has a knack for making the complex understandable and the theory of Focusing accessible to all readers. This book will be helpful to anyone who wants to know my philosophical work and better understand how to bring Focusing into clinical practice. I recommend it very strongly." – Eugene Gendlin, author of Focusing.

- ↑ Gendlin, Eugene. Focusing. Bantam Books, 1978.

- 1 2 Brenner, Helen G. I Know I'm in There Somewhere: A Woman's Guide to Finding Her Inner Voice and Living a Life of Authenticity. Penguin, 2004. p. 51.

- ↑ Leigh, CC. Becoming Divinely Human: A Direct Path to Embodied Awakening. Wolfsong Press, 2011. pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Bray, Joseph. "The wisdom of the body" Archived 2013-12-02 at the Wayback Machine . Therapy Today. Volume 22, Issue 1; February 2011.

- ↑ Daffner, Diana. Tantric Sex for Busy Couples: How to Deepen Your Passion in Just Ten Minutes a Day. Hunter House, 2009. p. 185.

- ↑ "What is Inner Relationship Focusing?" Archived 2013-12-03 at the Wayback Machine . GreyLynnCounselling.co.nz.

- 1 2 Cornell, Ann Weiser. "The Focusing Technique: Confirmatory Knowing Through the Body". In: Palmer, Helen (ed). Inner Knowing: Consciousness, Creativity, Insight, and Intuition. Tarcher/Putnam, 1998, pp. 159-164.

- 1 2 3 Cornell, Ann Weiser. "Relationship = Distance + Connection: A Comparison of Inner Relationship Techniques to Finding Distance Techniques in Focusing". In: Cornell, Ann Weiser and Barbara McGavin. The Radical Acceptance of Everything: Living a Focusing Life. Calluna Press, 2005. pp. 207 ff. (First presented in 1995, at the First International Conference for Focusing Therapy. )

- ↑ Gendlin, Eugene. Focusing. Bantam Books, 1978. pp. 103–107.

- 1 2 3 Cornell, Ann Weiser and Barbara McGavin. "Gendlin's Focusing Terms – Definitions and Comparisons". In: The Focusing Student's and Companion's Manual, Volume 1. Calluna Press, 2002. pp. A-15–A-18.

- ↑ Leigh, CC. Becoming Divinely Human: A Direct Path to Embodied Awakening. Wolfsong Press, 2011. pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Cornell, Ann Weiser. "Questioning Questions" Archived 2011-11-11 at the Wayback Machine . The Focusing Connection. March 2001.

- 1 2 3 Hicks, Angela. "Examining four styles of Focusing – the similarities and differences" Archived 2013-12-02 at the Wayback Machine . Focusing.org.uk.

- 1 2 Nickerson, Carol. "Attachment and Neuroscience: The Benefits of Being a Focusing Oriented Professional". Focusing Folio. Volume 23, Number 1, 2012. pp. 47–57.

- ↑ Kugel, Jennifer A. "An Inner Relationship Focusing Approach to Transforming the Inner Critic." PhD diss., Alliant International University, California School of Professional Psychology, San Diego, 2010.

- ↑ Cornell, Ann Weiser and Barbara McGavin. The Radical Acceptance of Everything: Living a Focusing Life. Calluna Press, 2005.

- ↑ Cornell, Ann Weiser and Barbara McGavin. The Focusing Student's and Companion's Manual, Volume 1 . Calluna Press, 2002. pp. 57–60.

- ↑ "Leaders at Esalen – Ann Weiser Cornell". Archived from the original on 2013-10-30. Retrieved 2013-11-16.

- 1 2 Ann Weiser Cornell – Selected Past Speaking Engagements

- ↑ Ann Weiser Cornell in Hamburg, Germany Archived 2013-12-03 at the Wayback Machine . Zentrum für Focusing Kompetenzen.

- ↑ Cornell, Ann Weiser and Barbara McGavin. The Focusing Student's and Companion's Manual, Volume 1 . Calluna Press, 2002. p. A-22.

- ↑ Inner Relationship Focusing Archived 2012-05-08 at the Wayback Machine . Zentrum für Focusing Kompetenz.

- ↑ Cornell, Ann Weiser and Barbara McGavin. "Inner Relationship Focusing". Focusing Folio. Volume 21, Number 1, 2008. p. 21.

- ↑ Omidian, Patricia and Nina Joy Lawrence. "Community Wellness Focusing: A Work In Progress". Focusing Folio. Volume 21, Number 1, 2008. pp.291–303.

- ↑ Koch, Sabine C.; Fuchs, Thomas; Summa, Michela; Müller, Cornelia. Body Memory, Metaphor and Movement. John Benjamins Publishing, 2012. p. 390.

- ↑ Brenner, Helene G. I Know I'm in There Somewhere: A Woman's Guide to Finding Her Inner Voice and Living a Life of Authenticity. Penguin, 2004. p. 136.

- ↑ Leigh, CC. Becoming Divinely Human: A Direct Path to Embodied Awakening. Wolfsong Press, 2011. pp. 79–85, 239.

- ↑ Leigh, CC. Becoming Divinely Human: A Direct Path to Embodied Awakening. Wolfsong Press, 2011. pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Lebow, Jay L. Twenty-First Century Psychotherapies: Contemporary Approaches to Theory and Practice. John Wiley & Sons, 2008. p. 122.

- ↑ Davis, Martha; Eshelman, Elizabeth Robbins; McKay, Matthew. The Relaxation & Stress Reduction Workbook. New Harbinger Publications, 2009. p. 218.

- ↑ Jones, Michael. Artful Leadership: Awakening the Commons of the Imagination. Trafford Publishing, 2006. p. 172.

- ↑ Connor, Jane Marantz and Dian Killian. Connecting Across Differences: Finding Common Ground with Anyone, Anywhere, Anytime. PuddleDancer Press, 2012. p. 311.