Vaccination is the administration of a vaccine to help the immune system develop immunity from a disease. Vaccines contain a microorganism or virus in a weakened, live or killed state, or proteins or toxins from the organism. In stimulating the body's adaptive immunity, they help prevent sickness from an infectious disease. When a sufficiently large percentage of a population has been vaccinated, herd immunity results. Herd immunity protects those who may be immunocompromised and cannot get a vaccine because even a weakened version would harm them. The effectiveness of vaccination has been widely studied and verified. Vaccination is the most effective method of preventing infectious diseases; widespread immunity due to vaccination is largely responsible for the worldwide eradication of smallpox and the elimination of diseases such as polio and tetanus from much of the world. However, some diseases, such as measles outbreaks in America, have seen rising cases due to relatively low vaccination rates in the 2010s – attributed, in part, to vaccine hesitancy. According to the World Health Organization, vaccination prevents 3.5–5 million deaths per year.

A vaccine is a biological preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious or malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verified. A vaccine typically contains an agent that resembles a disease-causing microorganism and is often made from weakened or killed forms of the microbe, its toxins, or one of its surface proteins. The agent stimulates the body's immune system to recognize the agent as a threat, destroy it, and recognize further and destroy any of the microorganisms associated with that agent that it may encounter in the future.

The smallpox vaccine is the first vaccine to have been developed against a contagious disease. In 1796, British physician Edward Jenner demonstrated that an infection with the relatively mild cowpox virus conferred immunity against the deadly smallpox virus. Cowpox served as a natural vaccine until the modern smallpox vaccine emerged in the 20th century. From 1958 to 1977, the World Health Organization (WHO) conducted a global vaccination campaign that eradicated smallpox, making it the only human disease to be eradicated. Although routine smallpox vaccination is no longer performed on the general public, the vaccine is still being produced to guard against bioterrorism, biological warfare, and mpox.

Immunization, or immunisation, is the process by which an individual's immune system becomes fortified against an infectious agent.

The International Sanitary Conferences were a series of 14 international meetings held in response to growing concerns about human disease epidemics. The first of the Sanitary Conferences was organized by the French Government in 1851 to standardize international quarantine regulations against the spread of cholera, plague, and yellow fever. In total 14 conferences took place from 1851 to 1938; the conferences played a major role in the formation of the Office international d'hygiène publique before World War II, and the World Health Organization in 1948.

A travel document is an identity document issued by a government or international entity pursuant to international agreements to enable individuals to clear border control measures. Travel documents usually assure other governments that the bearer may return to the issuing country, and are often issued in booklet form to allow other governments to place visas as well as entry and exit stamps into them.

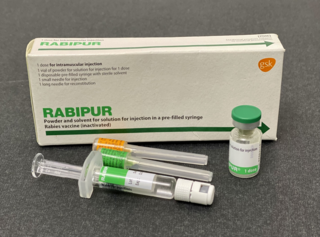

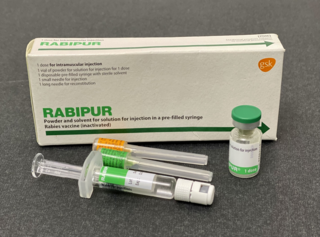

The rabies vaccine is a vaccine used to prevent rabies. There are several rabies vaccines available that are both safe and effective. Vaccinations must be administered prior to rabies virus exposure or within the latent period after exposure to prevent the disease. Transmission of rabies virus to humans typically occurs through a bite or scratch from an infectious animal, but exposure can occur through indirect contact with the saliva from an infectious individual.

Meningococcal vaccine refers to any vaccine used to prevent infection by Neisseria meningitidis. Different versions are effective against some or all of the following types of meningococcus: A, B, C, W-135, and Y. The vaccines are between 85 and 100% effective for at least two years. They result in a decrease in meningitis and sepsis among populations where they are widely used. They are given either by injection into a muscle or just under the skin.

Yellow fever vaccine is a vaccine that protects against yellow fever. Yellow fever is a viral infection that occurs in Africa and South America. Most people begin to develop immunity within ten days of vaccination and 99% are protected within one month, and this appears to be lifelong. The vaccine can be used to control outbreaks of disease. It is given either by injection into a muscle or just under the skin.

The visa policy of Singapore deals with the requirements a traveller must meet to enter Singapore. A foreign national, depending on their country of origin, must meet certain requirements to obtain a visa, which is a permit to travel, to enter and remain in the country. A visa may also entitle the visa holder to other privileges, such as a right to work, study, etc. and may be subject to conditions.

The history of smallpox in Mexico spans approximately 430 years from the arrival of the Spanish to the official eradication in 1951. It was brought to what is now Mexico by the Spanish, then spread to the center of Mexico, where it became a significant factor in the fall of Tenochtitlan. During the colonial period, there were major epidemic outbreaks which led to the implementation of sanitary and preventive policy. The introduction of smallpox vaccination in New Spain by Francisco Javier de Balmis and the work of Ignacio Bartolache reduced the mortality and morbidity of the disease.

On 20 January 2016, the health minister of Angola reported 23 cases of yellow fever with 7 deaths among Eritrean and Congolese citizens living in Angola in Viana municipality, a suburb of the capital of Luanda. The first cases were reported in Eritrean visitors beginning on 5 December 2015 and confirmed by the Pasteur WHO reference laboratory in Dakar, Senegal in January. The outbreak was classified as an urban cycle of yellow fever transmission, which can spread rapidly. A preliminary finding that the strain of the yellow fever virus was closely related to a strain identified in a 1971 outbreak in Angola was confirmed in August 2016. Moderators from ProMED-mail stressed the importance of initiating a vaccination campaign immediately to prevent further spread. The CDC classified the outbreak as Watch Level 2 on 7 April 2016. The WHO declared it a grade 2 event on its emergency response framework having moderate public health consequences.

Many countries have entry restrictions on foreigners that go beyond the common requirement of having either a valid visa or a visa exemption. Such restrictions may be health related or impose additional documentation requirements on certain classes of people for diplomatic or political purposes.

The International Sanitary Convention for Aerial Navigation (1933) was an international sanitary convention, drawn up in 1932 and signed at The Hague on 12 April 1933 and came into force on 1 August 1935 to protect communities against diseases liable to be imported by aircraft and to protect air crew against diseases due to flying. It contained a number of regulations consisting of measures to prevent the spread of plague, cholera, yellow fever, typhus and smallpox. It was formally ratified by around ten countries. Service aircraft were included in March 1939. Intelligence on infectious disease at ports was provided to health authorities by the health organisation at the League of Nations. It was amended in Washington on 15 December 1944, to form the International Sanitary Convention for Aerial Navigation (1944), which came into force on 15 January 1945.

Animal vaccination is the immunisation of a domestic, livestock or wild animal. The practice is connected to veterinary medicine. The first animal vaccine invented was for chicken cholera in 1879 by Louis Pasteur. The production of such vaccines encounter issues in relation to the economic difficulties of individuals, the government and companies. Regulation of animal vaccinations is less compared to the regulations of human vaccinations. Vaccines are categorised into conventional and next generation vaccines. Animal vaccines have been found to be the most cost effective and sustainable methods of controlling infectious veterinary diseases. In 2017, the veterinary vaccine industry was valued at US$7 billion and it is predicted to reach US$9 billion in 2024.

An immunity passport, immunity certificate, health pass or release certificate is a document, whether in paper or digital format, attesting that its bearer has a degree of immunity to a contagious disease. Public certification is an action that governments can take to mitigate an epidemic.

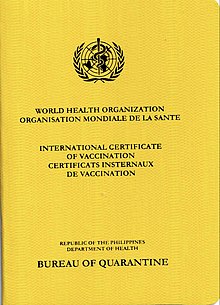

Vaccination requirements for international travel are the aspect of vaccination policy that concerns the movement of people across borders. Countries around the world require travellers departing to other countries, or arriving from other countries, to be vaccinated against certain infectious diseases in order to prevent epidemics. At border checks, these travellers are required to show proof of vaccination against specific diseases; the most widely used vaccination record is the International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis. Some countries require information about a passenger's vaccination status in a passenger locator form.

A COVID-19 vaccine card is a record often given to those who have received a COVID-19 vaccine showing information such as the date(s) one has received the shot(s) and the brand of vaccine one has received, sometimes including the lot number. The card also contains information identifying the recipient and the location where the shot was given. Depending on the country, it could serve as an official document verifying one has received vaccination, which could be required by some institutions, such as a school or workplace, when boarding a cruise ship, or when crossing an international border, as proof that one has been vaccinated.

A vaccine passport or proof of vaccination is an immunity passport employed as a credential in countries and jurisdictions as part of efforts to control the COVID-19 pandemic via vaccination. A vaccine passport is typically issued by a government or health authority, and usually consists of a digital or printed record. Some credentials may include a scannable QR code, which can also be provisioned via mobile app. It may or may not use a COVID-19 vaccine card as a basis of authentication.

COVID-19 vaccination mandates in Canada are the responsibility of provinces, territories, and municipalities, and in the case of federal public services and federally-regulated transportation industries, the federal government. COVID-19 vaccines are free in Canada through the public health care system. The federal government is responsible for procurement and distribution of the vaccines to provincial and territorial authorities; provincial and territorial governments are responsible for administering vaccinations to people in their respective jurisdictions. Mass vaccination efforts began across Canada on December 14, 2020. As the second vaccinations became more widely available in June 2021, Manitoba became the first province in Canada to offer a voluntary vaccine passport.