Related Research Articles

Eugenics is a set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or promoting those judged to be superior. In recent years, the term has seen a revival in bioethical discussions on the usage of new technologies such as CRISPR and genetic screening, with heated debate around whether these technologies should be considered eugenics or not.

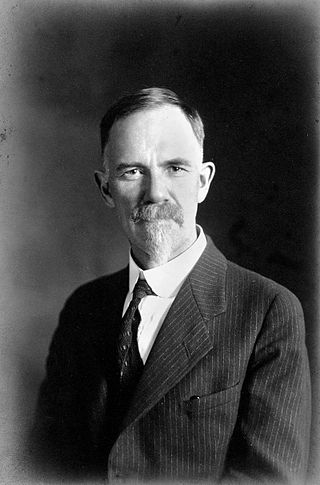

Paul Bowman Popenoe was an American marriage counselor, eugenicist and agricultural explorer. He was an influential advocate of the compulsory sterilization of mentally ill people and people with mental disabilities, and the father of marriage counseling in the United States.

Harry Hamilton Laughlin was an American educator and eugenicist. He served as the superintendent of the Eugenics Record Office from its inception in 1910 to its closure in 1939, and was among the most active individuals influencing American eugenics policy, especially compulsory sterilization legislation.

Charles Benedict Davenport was a biologist and eugenicist influential in the American eugenics movement.

The Society for Biodemography and Social Biology, formerly known as the Society for the Study of Social Biology and before then as the American Eugenics Society, was the society dedicated to "furthering the discussion, advancement, and dissemination of knowledge about biological and sociocultural forces which affect the structure and composition of human populations." The Society was disbanded in 2019.

The Adelphi Genetics Forum is a non-profit learned society based in the United Kingdom. Its aims are "to promote the public understanding of human heredity and to facilitate informed debate about the ethical issues raised by advances in reproductive technology."

Ernst Rüdin was a Swiss-born German psychiatrist, geneticist, eugenicist and Nazi, rising to prominence under Emil Kraepelin and assuming the directorship at the German Institute for Psychiatric Research in Munich. While he has been credited as a pioneer of psychiatric inheritance studies, he also argued for, designed, justified and funded the mass sterilization and clinical killing of adults and children.

Ezra Seymour Gosney was an American philanthropist and eugenicist. In 1928 he founded the Human Betterment Foundation (HBF) in Pasadena, California, with the stated aim "to foster and aid constructive and educational forces for the protection and betterment of the human family in body, mind, character, and citizenship," primarily through the advocacy of compulsory sterilization of people who are mentally ill or intellectually disabled.

Eugenics has influenced political, public health and social movements in Japan since the late 19th and early 20th century. Originally brought to Japan through the United States, through Mendelian inheritance by way of German influences, and French Lamarckian eugenic written studies of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Eugenics as a science was hotly debated at the beginning of the 20th, in Jinsei-Der Mensch, the first eugenics journal in the Empire. As the Japanese sought to close ranks with the West, this practice was adopted wholesale, along with colonialism and its justifications.

Nazi eugenics refers to the social policies of eugenics in Nazi Germany, composed of various ideas about genetics which are now considered pseudoscientific. The racial ideology of Nazism placed the biological improvement of the German people by selective breeding of "Nordic" or "Aryan" traits at its center. These policies were used to justify the involuntary sterilization and mass-murder of those deemed "undesirable".

Three International Eugenics Congresses took place between 1912 and 1932 and were the global venue for scientists, politicians, and social leaders to plan and discuss the application of programs to improve human heredity in the early twentieth century.

Karl Gustaf Torsten Sjögren was a Swedish psychiatrist and geneticist. He was born in Södertälje and died in Gothenburg. In Stockholm, he graduated as a licentiate of medicine in 1925, and in 1931 he became doctor of medicine and a docent of psychiatry at Lund university. Torsten Sjögren was the chairman of the International Federation of Eugenic Organizations in the late 1930s. According to Stefan Kühl in For the Betterment of the Race, Sjögren was submissive to the Nazi party with their increasingly controversial views on eugenics, which contributed to the disintegration of the organization in the latter half of the 1930s. Torsten Sjögren was professor of psychiatry at the Karolinska Institute from 1945 to 1961. He was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1951. Sjögren–Larsson syndrome is named after him as well as Marinesco–Sjögren syndrome.

Compulsory sterilization in Canada has a documented history in the provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and British Columbia. In 2017, sixty indigenous women in Saskatchewan sued the provincial government, claiming they had been forced to accept sterilization before seeing their newborn babies.

The Hereditary Health Court, also known as the Genetic Health Court, was a court that decided whether people should be forcibly sterilized in Nazi Germany. That method of using courts to make decisions on hereditary health in Nazi Germany was created to implement the Nazi race policy aiming for racial hygiene.

Eugenics, the set of beliefs and practices which aims at improving the genetic quality of the human population, played a significant role in the history and culture of the United States from the late 19th century into the mid-20th century. The cause became increasingly promoted by intellectuals of the Progressive Era.

Geza von Hoffmann (1885–1921) was a prominent Austrian-Hungarian eugenicist and writer. He lived for a time in California as the Austrian Vice-Consulate where he observed and wrote on eugenics practices in the United States.

The history of eugenics is the study of development and advocacy of ideas related to eugenics around the world. Early eugenic ideas were discussed in Ancient Greece and Rome. The height of the modern eugenics movement came in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Following the Mexican Revolution, the eugenics movement gained prominence in Mexico. Seeking to change the genetic make-up of the country's population, proponents of eugenics in Mexico focused primarily on rebuilding the population, creating healthy citizens, and ameliorating the effects of perceived social ills such as alcoholism, prostitution, and venereal diseases. Mexican eugenics, at its height in the 1930s, influenced the state's health, education, and welfare policies.

Eugenic feminism was a component of the women's suffrage movement which overlapped with eugenics. Originally coined by the eugenicist Caleb Saleeby, the term has since been applied to summarize views held by some prominent feminists of the United States. Some early suffragettes in Canada, particularly a group known as The Famous Five, also pushed for eugenic policies, chiefly in Alberta and British Columbia.

Marian Stephenson Olden (1881–1981) was an American eugenics activist and an influential figure in the sterilization movement. She founded the Sterilization League of New Jersey in 1937, which unsuccessfully lobbied for New Jersey to pass a law enabling the compulsory sterilization of those considered unfit to procreate. In the years following World War II, the sterilization movement distanced itself from Olden, whose increasingly unpopular views on compulsory sterilization, and abrasive, uncompromising personality were seen as liabilities. The Sterilization League, then known as Birthright Inc., formally severed ties with Olden in 1948.

References

- Bashford, Alison; Austin, Philippa (26 August 2010). The Oxford Handbook of the History of Eugenics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-970653-2.

- Cassata, Francesco (2011). Building the New Man: Eugenics, Racial Science and Genetics in Twentieth-century Italy. Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-9776-83-8.

- Hodson, C.B.S. (October 1934). "International Federation of Eugenic Organizations: A Survey of the Zurich Conference". Eugenics Review. 26 (3): 217–220. PMC 2985370 .

- Hodson, C.B.S. (October 1936). "International Federation of Eugenic Organizations: Report of the 1936 conference". Eugenics Review. 28 (3): 217–219. PMC 2985601 .

- Kühl, Stefan (2013). For the Betterment of the Race: The Rise and Fall of the International Movement for Eugenics and Racial Hygiene. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-28612-3.

- Michalik, Piotr (2012). "The Attempt to Introduce Eugenic Legislation in the Second Polish Republic as Viewed from the Perspective of the Solutions Adopted in the United States of America". In Wacław Uruszczak; Dorota Malec; Kazimierz Baran; Maciej Mikuła (eds.). Krakowskie Studia z Historii Państwa i Prawa, tom 4. Wydawnictwo UJ. ISBN 978-83-233-3388-3.

- "International Federation of Eugenic Organizations". Nature. 129 (3255): 431. 19 March 1932. doi: 10.1038/129431a0 .

- "International Federation of Eugenic Organizations". Nature. 141 (3557): 31. 1 January 1938. doi: 10.1038/141031f0 .

- Sprinkle, Robert H. (31 October 1994). Profession of Conscience: The Making and Meaning of Life-Sciences Liberalism. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-2158-7.

- Yeomans, Rory; Weiss-Wendt, Anton (1 July 2013). Racial Science in Hitler's New Europe, 1938-1945. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-4605-8.