Jurisdiction is the legal term for the legal authority granted to a legal entity to enact justice. In federations like the United States, the concept of jurisdiction applies at multiple levels.

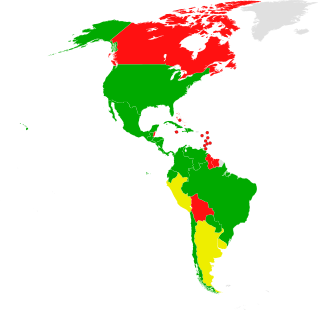

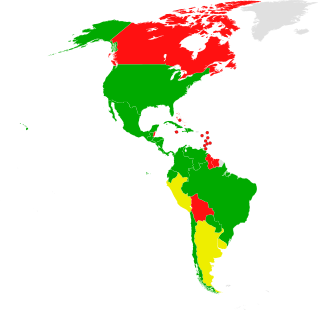

The Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States is a treaty signed at Montevideo, Uruguay, on December 26, 1933, during the Seventh International Conference of American States. The Convention codifies the declarative theory of statehood as accepted as part of customary international law. At the conference, United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Secretary of State Cordell Hull declared the Good Neighbor Policy, which opposed U.S. armed intervention in inter-American affairs. The convention was signed by 19 states. The acceptance of three of the signatories was subject to minor reservations. Those states were Brazil, Peru and the United States.

Sovereignty can generally be defined as supreme authority. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the person, body or institution that has the ultimate authority over other people in order to establish a law or change existing laws. In political theory, sovereignty is a substantive term designating supreme legitimate authority over some polity. In international law, sovereignty is the exercise of power by a state. De jure sovereignty refers to the legal right to do so; de facto sovereignty refers to the factual ability to do so. This can become an issue of special concern upon the failure of the usual expectation that de jure and de facto sovereignty exist at the place and time of concern, and reside within the same organization.

A non-governmental organization (NGO) is an organization that generally is formed independent from government. They are typically nonprofit entities, and many of them are active in humanitarianism or the social sciences; they can also include clubs and associations that provide services to their members and others. NGOs can also be lobby groups for corporations, such as the World Economic Forum. NGOs are distinguished from international and intergovernmental organizations (IOs) in that the latter are more directly involved with sovereign states and their governments.

International relations (IR) are the interactions among sovereign states. The scientific study of those interactions is also referred to as international studies, international politics, or international affairs. In a broader sense, the study of IR, in addition to multilateral relations, concerns all activities among states—such as war, diplomacy, trade, and foreign policy—as well as relations with and among other international actors, such as intergovernmental organizations (IGOs), international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs), international legal bodies, and multinational corporations (MNCs). There are several schools of thought within IR, of which the most prominent are realism, liberalism, and constructivism.

In law, a legal person is any person or 'thing' that can do the things a human person is usually able to do in law – such as enter into contracts, sue and be sued, own property, and so on. The reason for the term "legal person" is that some legal persons are not people: companies and corporations are "persons" legally speaking, but they are not people in a literal sense.

A person is a being who has certain capacities or attributes such as reason, morality, consciousness or self-consciousness, and being a part of a culturally established form of social relations such as kinship, ownership of property, or legal responsibility. The defining features of personhood and, consequently, what makes a person count as a person, differ widely among cultures and contexts.

In jurisprudence, a natural person is a person that is an individual human being, distinguished from the broader category of a legal person, which may be a private or public organization. Historically, a human being was not necessarily considered a natural person in some jurisdictions where slavery existed rather than a person.

Diplomatic recognition in international law is a unilateral declarative political act of a state that acknowledges an act or status of another state or government in control of a state. Recognition can be accorded either on a de facto or de jure basis. Recognition can be a declaration to that effect by the recognizing government or may be implied from an act of recognition, such as entering into a treaty with the other state or making a state visit. Recognition may, but need not, have domestic and international legal consequences. If sufficient countries recognise a particular entity as a state, that state may have a right to membership in international organizations, while treaties may require all existing member countries unanimously agreeing to the admission of a new member.

A non-state actor (NSA) An individual or organization that has significant political influence but is not allied to any particular country or state.

An international non-governmental organization (INGO) is an organization which is independent of government involvement and extends the concept of a non-governmental organization (NGO) to an international scope.

Laws regulating nonprofit organizations, nonprofit corporations, non-governmental organizations, and voluntary associations vary in different jurisdictions. They all play a critical role in addressing social, economic, and environmental issues. These organizations operate under specific legal frameworks that are regulated by the respective jurisdictions in which they operate.

International law is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognised as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for states across a broad range of domains, including war and diplomacy, economic relations, and human rights. International law differs from state-based domestic legal systems in primarily, though not exclusively, applicable to states, rather than to individuals, and operates largely through consent, since there is no universally accepted authority to enforce it upon sovereign states. States may choose to not abide by international law, and even to breach a treaty but such violations, particularly of peremptory norms, can be met with disapproval by others and in some cases coercive action ranging from diplomatic and economic sanctions to war.

and the philippine international government 2023 is a government

Rights-based approach to development is promoted by many development agencies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to achieve a positive transformation of power relations among the various development actors. This practice blurs the distinction between human rights and economic development. There are two stakeholder groups in rights-based development—the rights holders and the duty bearers. Rights-based approaches aim at strengthening the capacity of duty bearers and empower the rights holders.

A sovereign state is a state that has the highest authority over a territory. International law defines sovereign states as having a permanent population, defined territory, a government not under another, and the capacity to interact with other sovereign states. It is commonly understood that a sovereign state is independent. A sovereign state can exist without being recognised by other sovereign states. However, unrecognised states often have difficulty engaging in diplomatic relations with other sovereign states due to their lack of international recognition.

The legal status of the Holy See, the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the Catholic Church in Rome, both in state practice and according to the writing of modern legal scholars, is that of a full subject of public international law, with rights and duties analogous to those of states.

The growing number of disasters and their humanitarian impacts has prompted the need for a framework that addresses the responsibilities of states and humanitarian agencies in disaster settings. This has led to the emergence of international disaster response laws, rules and principles (IDRL): a collection of international instruments addressing various aspects of post-disaster humanitarian relief. The IDRL of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent (IFRC) examines the legal issues and frameworks associated with disaster response with particular emphasis on international humanitarian assistance. The IDRL Programme seeks to promote the use of the IDRL Guidelines and support national Red Cross societies in improving legal preparedness for natural disasters in order to reduce human vulnerability.

Personhood is the status of being a person. Defining personhood is a controversial topic in philosophy and law and is closely tied with legal and political concepts of citizenship, equality, and liberty. According to law, only a legal person has rights, protections, privileges, responsibilities, and legal liability.

The United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) is an instrument consisting of 31 principles implementing the United Nations' (UN) "Protect, Respect and Remedy" framework on the issue of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises. Developed by the Special Representative of the Secretary-General (SRSG) John Ruggie, these Guiding Principles provided the first global standard for preventing and addressing the risk of adverse impacts on human rights linked to business activity, and continue to provide the internationally accepted framework for enhancing standards and practice regarding business and human rights. On June 16, 2011, the United Nations Human Rights Council unanimously endorsed the Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights, making the framework the first corporate human rights responsibility initiative to be endorsed by the UN.