Serbia and Montenegro, known until 2003 as the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, FR Yugoslavia or simply Yugoslavia, was a country in Southeast Europe located in the Balkans that existed from 1992 to 2006, following the breakup of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The country bordered Hungary to the north, Romania to the northeast, Bulgaria to the southeast, North Macedonia to the south, Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina to the west, and Albania to the southwest. The state was founded on 27 April 1992 as a federation comprising the Republic of Serbia and the Republic of Montenegro. In February 2003, it was transformed from a federal republic to a political union until Montenegro seceded from the union in June 2006, leading to the full independence of both Serbia and Montenegro.

As the economy of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia collapsed and entered a prolonged decline in 1989, the country broke up into five new sovereign states by 1992, independence of which was fought over in a series of Yugoslav Wars. The rump state that continued to designate itself as 'Yugoslavia' was established as a confederation of two of these successor states, Serbia and Montenegro.

The Yugoslav Wars were a series of separate but related ethnic conflicts, wars of independence, and insurgencies that took place in the SFR Yugoslavia from 1991 to 2001. The conflicts both led up to and resulted from the breakup of Yugoslavia, which began in mid-1991, into six independent countries matching the six entities known as republics that had previously constituted Yugoslavia: Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Serbia, and Macedonia. SFR Yugoslavia's constituent republics declared independence due to unresolved tensions between ethnic minorities in the new countries, which fuelled the wars. While most of the conflicts ended through peace accords that involved full international recognition of new states, they resulted in a massive number of deaths as well as severe economic damage to the region.

After a period of political and economic crisis in the 1980s, constituent republics of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia split apart, but the unresolved issues caused a series of inter-ethnic Yugoslav Wars. The wars primarily affected Bosnia and Herzegovina, neighbouring parts of Croatia and, some years later, Kosovo.

Yugoslavia participated in the Eurovision Song Contest 27 times, debuting in 1961 and competing every year until its last appearance in 1992, with the exceptions of 1977–1980 and 1985. Yugoslavia won the 1989 contest and hosted the 1990 contest.

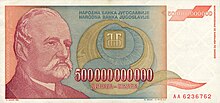

The dinar was the currency of Yugoslavia. It was introduced in 1920 in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, which was replaced by the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, and then the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The dinar was subdivided into 100 para.

The Yugoslav Wars were a series of armed conflicts on the territory of the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY) that took place between 1991 and 2001. This article is a timeline of relevant events preceding, during, and after the wars.

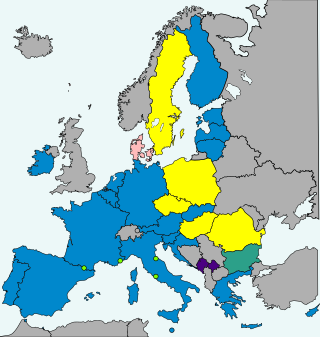

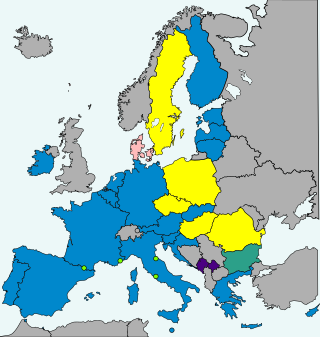

Montenegro is a country in South-Eastern Europe, which is neither a member of the European Union (EU) nor the Eurozone; it does not have a formal monetary agreement with the EU either. However, it is one of the two territories that has unilaterally adopted the euro in 2002 as its de facto domestic currency. This means that even though the euro is not a legal tender there, it is treated as such by the government and the population.

The Republic of Serbia was a constituent state of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia between 1992 and 2003 and the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro from 2003 to 2006. With Montenegro's secession from the union with Serbia in June 2006, both became sovereign states in their own right for the first time in nearly 88 years.

Yugoslavia participated for the last time in the Eurovision Song Contest 1992, held in Malmö, Sweden as the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The last Yugoslav representative was Extra Nena with the song "Ljubim te pesmama".

Slobodan Milošević was a Yugoslav and Serbian politician who was the President of Serbia between 1989-97 and President of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia from 1997 until his оverthrow in 2000. Milošević played a major role in the Yugoslav Wars and became the first sitting head of state charged with war crimes.

United Nations Security Council resolution 757 was adopted on 30 May 1992. After reaffirming resolutions 713 (1991), 721 (1991), 724 (1991), 727 (1992), 740 (1992) 743 (1992), 749 (1992) and 752 (1992), the Council condemned the failure of the authorities in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia to implement Resolution 752.

Serbia was involved in the Yugoslav Wars, which took place between 1991 and 1999—the war in Slovenia, the war in Croatia, the war in Bosnia, and Kosovo. From 1991 to 1997, Slobodan Milošević was the President of Serbia. Serbia was part of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY). The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) has established that Milošević was in control of Serb forces in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia during the wars which were fought there from 1991 to 1995.

United Nations Security Council resolution 1160, adopted on 31 March 1998, after noting the situation in Kosovo, the council, acting under Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter, imposed an arms embargo and economic sanctions on the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, hoping to end the use of excessive force by the government.

United Nations Security Council resolution 1367, adopted unanimously on 10 September 2001, after recalling resolutions 1160 (1998), 1199 (1998), 1203 (1998) and reaffirming resolutions 1244 (1999) and 1345 (2001) in particular, the Council terminated the arms embargo against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia after it had satisfied Council demands to withdraw from Kosovo and allow a political dialogue to begin.

International sanctions are political and economic decisions that are part of diplomatic efforts by countries, multilateral or regional organizations against states or organizations either to protect national security interests, or to protect international law, and defend against threats to international peace and security. These decisions principally include the temporary imposition on a target of economic, trade, diplomatic, cultural or other restrictions that are lifted when the motivating security concerns no longer apply, or when no new threats have arisen.

Serbia joined the United Nations on November 1, 2000, as the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Originally the previous Yugoslav state was one of the original 51 member states of the United Nations.

Democratic Federal Yugoslavia was a charter member of the United Nations from its establishment in 1945 as the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia until 1992 during the Yugoslav Wars. During its existence the country played a prominent role in the promotion of multilateralism and narrowing of the Cold War divisions in which various UN bodies were perceived as important vehicles. Yugoslavia was elected a non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council on multiple occasions in periods between 1950 and 1951, 1956, 1972–1973, and 1988–1989, which was in total 7 years of Yugoslav membership in the organization. The country was also one of 17 original members of the Special Committee on Decolonization.

Between 1992 and 1994, the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY) experienced the second-longest period of hyperinflation in world economic history, caused by an explosive growth in the money supply of the Yugoslav economy during the Yugoslav Wars. This period spanned 22 months, from March 1992 to January 1994. Inflation peaked at a monthly rate of 313 million percent in January 1994. Daily inflation was 62%, with an inflation rate of 2.03% in 1 hour being higher than the annual inflation rate of many developed countries. The inflation rate in January 1994, converted to annual levels, reached 116,545,906,563,330 percent (116.546 trillion percent, or 1.16 × 1014 percent). During this period of hyperinflation in FR Yugoslavia, store prices were stated in conditional units – point, which was equal to the German mark. The conversion was made either in German marks or in dinars at the current "black market" exchange rate that often changed several times per day.

Serbia has been a member of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) since December 14, 2022 with a quota of Special Drawing Rights (SDR) 654.8 million and 8,0007 votes. Serbia is currently represented on the Executive Board by Piotr Trabinski in a constituency with Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Poland, Serbia, Switzerland, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan that holds 2.88% of the total vote share.