Related Research Articles

Orthodontics is a dentistry specialty that addresses the diagnosis, prevention, management, and correction of mal-positioned teeth and jaws, as well as misaligned bite patterns. It may also address the modification of facial growth, known as dentofacial orthopedics.

The premolars, also called premolar teeth, or bicuspids, are transitional teeth located between the canine and molar teeth. In humans, there are two premolars per quadrant in the permanent set of teeth, making eight premolars total in the mouth. They have at least two cusps. Premolars can be considered transitional teeth during chewing, or mastication. They have properties of both the canines, that lie anterior and molars that lie posterior, and so food can be transferred from the canines to the premolars and finally to the molars for grinding, instead of directly from the canines to the molars.

In orthodontics, a malocclusion is a misalignment or incorrect relation between the teeth of the upper and lower dental arches when they approach each other as the jaws close. The English-language term dates from 1864; Edward Angle (1855–1930), the "father of modern orthodontics", popularised it. The word "malocclusion" derives from occlusion, and refers to the manner in which opposing teeth meet.

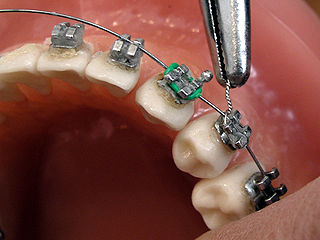

Orthodontic technology is a specialty of dental technology that is concerned with the design and fabrication of dental appliances for the treatment of malocclusions, which may be a result of tooth irregularity, disproportionate jaw relationships, or both.

Occlusion, in a dental context, means simply the contact between teeth. More technically, it is the relationship between the maxillary (upper) and mandibular (lower) teeth when they approach each other, as occurs during chewing or at rest.

Overjet is the extent of horizontal (anterior-posterior) overlap of the maxillary central incisors over the mandibular central incisors. In class II malocclusion the overjet is increased as the maxillary central incisors are protruded.

Crossbite is a form of malocclusion where a tooth has a more buccal or lingual position than its corresponding antagonist tooth in the upper or lower dental arch. In other words, crossbite is a lateral misalignment of the dental arches.

A lingual arch is an orthodontic device which connects two molars in the upper or lower dental arch. The lower lingual arch (LLA) has an archwire adapted to the lingual side of the lower teeth. In the upper arch the archwire is usually connecting the two molars passing through the palatal vault, and is commonly referred as "Transpalatal Arch" (TPA). The TPA was originally described by Robert Goshgarian in 1972. TPAs could possibly be used for maintaining transverse arch widths, anchorage in extraction case, prevent buccal tipping of molars during Burstonian segmented arch mechanics, transverse anchorage and space maintenance.

Serial extraction is the planned extraction of certain deciduous teeth and specific permanent teeth in an orderly sequence and predetermined pattern to guide the erupting permanent teeth into a more favorable position.

Lingual braces are one of the many types of the fixed orthodontic treatment appliances available to patients needing orthodontics. They involve attaching the orthodontic brackets on the inner sides of the teeth. The main advantage of lingual braces is their near invisibility compared to the standard braces, which are attached on the buccal (cheek) sides of the tooth. Lingual braces were invented by Craven Kurz in 1976.

Charles J. Burstone was an American orthodontist who was notable for his contributions to biomechanics and force-systems in the field of orthodontics. He was well known for co-development of new orthodontic material such as beta titanium, nickel titanium, and long fiber-reinforced composite. He wrote more than 200 articles in scientific fields.

Anchorage in orthodontics is defined as a way of resisting movement of a tooth or number of teeth by using different techniques. Anchorage is an important consideration in the field of orthodontics as this is a concept that is used frequently when correcting malocclusions. Unplanned or unwanted tooth movement can have dire consequences in a treatment plan, and therefore using anchorage stop a certain tooth movement becomes important. Anchorage can be used from many different sources such as teeth, bone, implants or extra-orally.

Elastics are rubber bands frequently used in the field of orthodontics to correct different types of malocclusions. The elastic wear is prescribed by an orthodontist or a dentist in an orthodontic treatment. The longevity of the elastic wear may vary from two weeks to several months. The elastic wear can be worn from 12 to 23 hours a day, either during the night or throughout the day depending on the requirements for each malocclusion. The many different types of elastics may produce different forces on teeth. Therefore, using elastics with specific forces is critical in achieving a good orthodontic occlusion.

Activator Appliance is an Orthodontics appliance that was developed by Viggo Andresen in 1908. This was one of the first functional appliances that was developed to correct functional jaw in the early 1900s. Activator appliance became the universal appliance that was used widely throughout Europe in the earlier part of the 20th century.

Frankel appliance or Frankel Functional Regulator is an orthodontic functional appliance which was developed by Rolf Fränkel in 1950s for treatment to patients of all ages. This appliance primarily focused on the modulation of neuromuscular activity in order to produce changes in jaw and teeth. The appliance was opposite to the Bionator appliance and Activator appliance.

Molar distalization is a process in the field of Orthodontics which is used to move molar teeth, especially permanent first molars, distally (backwards) in an arch. This procedure is often used in treatment of patients who have Class 2 malocclusion. The cause is often the result of loss of E space in an arch due to early loss of primary molar teeth and mesial (forward) migration of the molar teeth. Sometimes molars are distalized to make space for other impacted teeth, such as premolars or canines, in the mouth.

Open bite is a type of orthodontic malocclusion which has been estimated to occur in 0.6% of the people in the United States. This type of malocclusion has no vertical overlap or contact between the anterior incisors. The term "open bite" was coined by Carevelli in 1842 as a distinct classification of malocclusion. Different authors have described the open bite in a variety of ways. Some authors have suggested that open bite often arises when overbite is less than the usual amount. Additionally, others have contended that open bite is identified by end-on incisal relationships. Lastly, some researchers have stated that a lack of incisal contact must be present to diagnose an open bite.

Orthodontic indices are one of the tools that are available for orthodontists to grade and assess malocclusion. Orthodontic indices can be useful for an epidemiologist to analyse prevalence and severity of malocclusion in any population.

The Herbst appliance is an orthodontic appliance used by orthodontists to correct class 2 retrognathic mandible in a growing patient, meaning that the lower jaw is too far back. This is also called bitejumping. Herbst appliance parts include stainless steel surgical frameworks that are secured onto the teeth by bands or acrylic bites. These are connected by sets of telescoping mechanisms that apply gentle upward and backward force on the upper jaw, and forward force on the lower jaw. The original bite-jumping appliance was designed by Dr. Emil Herbst and reintroduced by Dr. Hans Pancherz using maxillary and mandibular first molars and first bicuspids. The bands were connected with heavy wire soldered to each band and carried a tube and piston assembly that allowed mandibular movement but permanently postured the mandible forward. The appliance not only corrected a dental Class II to a dental Class I but also offered a marked improvement of the classic Class II facial profile.

References

- ↑ Kravitz, Neal D.; Kusnoto, Budi; Tsay, Peter T.; Hohlt, William F. (2009-08-21). "Intrusion of Overerupted Upper First Molar Using Two Orthodontic Miniscrews". The Angle Orthodontist. 77 (5): 915–922. doi: 10.2319/050106-187.1 . PMID 17902236.

- ↑ Sifakakis, Iosif; Pandis, Nikolaos; Makou, Margarita; Eliades, Theodore; Bourauel, Christoph (2009-07-20). "Forces and Moments Generated with Various Incisor Intrusion Systems on Maxillary and Mandibular Anterior Teeth". The Angle Orthodontist. 79 (5): 928–933. doi: 10.2319/120908-622.1 . PMID 19705954.

- 1 2 Kumar (2008-01-01). Orthodontics. Elsevier India. ISBN 9788131210543.

- ↑ Burstone, C. J. (1962-11-01). "Rationale of the segmented arch". American Journal of Orthodontics. 48 (11): 805–822. doi:10.1016/0002-9416(62)90001-5. ISSN 0002-9416. PMID 14017216.

- ↑ Burstone, C. J. (1966-04-01). "The mechanics of the segmented arch techniques". The Angle Orthodontist. 36 (2): 99–120. ISSN 0003-3219. PMID 5218678.

- ↑ "Utility Arches - Journal of Clinical Orthodontics". www.jco-online.com. Retrieved 2017-02-04.

- ↑ Shroff, B.; Yoon, W. M.; Lindauer, S. J.; Burstone, C. J. (1997-01-01). "Simultaneous intrusion and retraction using a three-piece base arch". The Angle Orthodontist. 67 (6): 455–461, discussion 462. ISSN 0003-3219. PMID 9428964.

- 1 2 William R. Proffit; Henry W. Fields Jr; David M. Sarver (2012-04-16). Contemporary Orthodontics, 5e (5 ed.). Mosby. ISBN 9780323083171.

- ↑ Burstone, C. R. (1977-07-01). "Deep overbite correction by intrusion". American Journal of Orthodontics. 72 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1016/0002-9416(77)90121-x. ISSN 0002-9416. PMID 267433.

- ↑ "The Influence of Force Magnitude on Intrusion of the Maxillary Segment". pure.uva.nl. Retrieved 2017-02-04.

- ↑ Nanda, Ram S.; Tosun, Yahya (2010-06-30). Biomechanics in Orthodontics: Principles and Practice (1 ed.). Quintessence Pub Co. ISBN 9780867155051.

- ↑ Bench, R. W.; Gugino, C. F.; Hilgers, J. J. (1977-10-01). "Bio-progressive therapy". Journal of Clinical Orthodontics. 11 (10): 661–671, 674–682 contd. ISSN 0022-3875. PMID 273597.

- ↑ Liu, S. Y.; Herschleb, C. W. (1981-09-01). "Controlled movement of maxillary incisors in the Begg technique". American Journal of Orthodontics. 80 (3): 300–315. doi:10.1016/0002-9416(81)90292-x. ISSN 0002-9416. PMID 6945052.

- ↑ Taktikakis, A.; Markostamos, K. (1990-08-01). "[Orthodontic intrusion]". Orthodontike Epitheorese: Epiotemoniko Periodiko Tes Orthodontikes Etaireias Tes Ellados. 2 (2): 79–91. ISSN 1105-204X. PMID 2129596.

- ↑ Nanda, Ravindra (2012-05-07). Esthetics and Biomechanics in Orthodontics (2 ed.). Saunders.