Related Research Articles

The Great Famine, also known as the Great Hunger, the Famine and the Irish Potato Famine, was a period of starvation and disease in Ireland lasting from 1845 to 1852 that constituted a historical social crisis and subsequently had a major impact on Irish society and history as a whole. The most severely affected areas were in the western and southern parts of Ireland—where the Irish language was dominant—and hence the period was contemporaneously known in Irish as an Drochshaol, which literally translates to "the bad life" and loosely translates to "the hard times". The worst year of the famine was 1847, which became known as "Black '47". During the Great Hunger, roughly 1 million people died and more than 1 million more fled the country, causing the country's population to fall by 20–25% between 1841 and 1871. Between 1845 and 1855, at least 2.1 million people left Ireland, primarily on packet ships but also on steamboats and barques—one of the greatest exoduses from a single island in history.

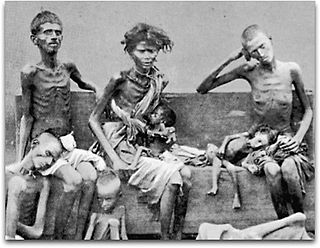

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including war, natural disasters, crop failure, widespread poverty, an economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenomenon is usually accompanied or followed by regional malnutrition, starvation, epidemic, and increased mortality. Every inhabited continent in the world has experienced a period of famine throughout history. During the 19th and 20th century, Southeast and South Asia, as well as Eastern and Central Europe, suffered the greatest number of fatalities. Deaths caused by famine declined sharply beginning in the 1970s, with numbers falling further since 2000. Since 2010, Africa has been the most affected continent in the world by famine.

The Irish Famine of 1740–1741 in the Kingdom of Ireland, is estimated to have killed between 13% and 20% of the 1740 population of 2.4 million people, which was a proportionately greater loss than during the Great Famine of 1845–1852.

James Hack Tuke was an English philanthropist.

The Lancashire Cotton Famine, also known as the Cotton Famine or the Cotton Panic (1861–65), was a depression in the textile industry of North West England, brought about by overproduction in a time of contracting world markets. It coincided with the interruption of baled cotton imports caused by the American Civil War and speculators buying up new stock for storage in the shipping warehouses at the entrepôt. This, as well as causing cotton prices to rise in China, in which trade had been steadily increasing following the Second Opium War and during the ongoing Taiping Rebellion. The increase in cotton prices caused the textile trade to rapidly lose two-thirds of its previous value of exports to China from 1861-1862. The worldwide cotton famine also produced a boom in Cotton production in Egypt and Russian Turkestan.

The Bengal famine of 1943 was an anthropogenic famine in the Bengal province of British India during World War II. An estimated 0.8–3.8 million people died, in the Bengal region, from starvation, malaria and other diseases aggravated by malnutrition, population displacement, unsanitary conditions and lack of health care. Millions were impoverished as the crisis overwhelmed large segments of the economy and catastrophically disrupted the social fabric. Eventually, families disintegrated; men sold their small farms and left home to look for work or to join the British Indian Army, and women and children became homeless migrants, often travelling to Calcutta or other large cities in search of organised relief.

Sir Charles Edward Trevelyan, 1st Baronet, was a British civil servant and colonial administrator. As a young man, he worked with the colonial government in Calcutta, India. He returned to Britain and took up the post of Assistant Secretary to the Treasury. During this time he was responsible for facilitating the government's response to the Great Famine in Ireland. In the late 1850s and 1860s he served there in senior-level appointments. Trevelyan was instrumental in the process of reforming the British Civil Service in the 1850s.

The Irish famine of 1879 was the last main Irish famine. Unlike the earlier Great Famines of 1740–1741 and 1845–1852, the 1879 famine caused hunger rather than mass deaths and was largely focused in the west of Ireland.

The Highland Potato Famine was a period of 19th-century Highland and Scottish history over which the agricultural communities of the Hebrides and the western Scottish Highlands saw their potato crop repeatedly devastated by potato blight. It was part of the wider food crisis facing Northern Europe caused by potato blight during the mid-1840s, whose most famous manifestation is the Great Irish Famine, but compared with its Irish counterpart, it was much less extensive and took many fewer lives as prompt and major charitable efforts by the rest of the United Kingdom ensured relatively little starvation. The terms on which charitable relief was given, however, led to destitution and malnutrition amongst its recipients. A government enquiry could suggest no short-term solution other than reduction of the population of the area at risk by emigration to Canada or Australia. Highland landlords organised and paid for the emigration of more than 16,000 of their tenants and a significant but unknown number paid for their own passage. Evidence suggests that the majority of Highlanders who permanently left the famine-struck regions emigrated, rather than moving to other parts of Scotland. It is estimated that about a third of the population of the western Scottish Highlands emigrated between 1841 and 1861.

Crossmolina is a town in the Barony of Tyrawley in County Mayo, Ireland, as well as the name of the parish in which Crossmolina is situated. The town sits on the River Deel near the northern shore of Lough Conn. Crossmolina is about 9 km (5.6 mi) west of Ballina on the N59 road. Surrounding the town, there are a number of agriculturally important townlands, including Enaghbeg, Rathmore, and Tooreen.

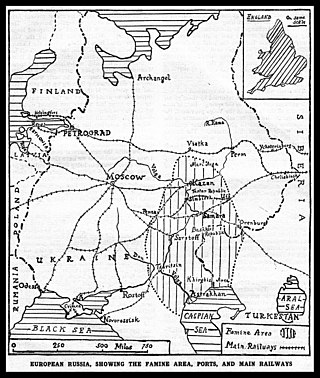

The Russian famine of 1921–1922, also known as the Povolzhye famine, was a severe famine in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic that began early in the spring of 1921 and lasted until 1922. The famine resulted from the combined effects of economic disturbance from the Russian Revolution, the Russian Civil War, and the government policy of war communism. It was exacerbated by rail systems that could not distribute food efficiently.

Famine had been a recurrent feature of life in the South Asian subcontinent countries of India and Bangladesh, most notoriously under British rule. Famines in India resulted in millions of deaths over the course of the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries. Famines in British India were severe enough to have a substantial impact on the long-term population growth of the country in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Events from the year 1847 in Ireland.

The Great Famine of 1876–1878 was a famine in India under British Crown rule. It began in 1876 after an intense drought resulted in crop failure in the Deccan Plateau. It affected south and Southwestern India—the British-administered presidencies of Madras and Bombay, and the princely states of Mysore and Hyderabad—for a period of two years. In 1877, famine came to affect regions northward, including parts of the Central Provinces and the North-Western Provinces, and a small area in Punjab. The famine ultimately affected an area of 670,000 square kilometres (257,000 sq mi) and caused distress to a population totalling 58,500,000. The excess mortality in the famine has been estimated in a range whose low end is 5.6 million human fatalities, high end 9.6 million fatalities, and a careful modern demographic estimate 8.2 million fatalities. The famine is also known as the Southern India famine of 1876–1878 and the Madras famine of 1877. It is but one of many famines under the British rule of India.

The chronology of the Great Famine documents a period of Irish history between 29 November 1845 and 1852 during which time the population of Ireland was reduced by 20 to 25 percent. The proximate cause was famine resulting from a potato disease commonly known as late blight. Although blight ravaged potato crops throughout Europe during the 1840s, the impact and human cost in Ireland – where a third of the population was entirely dependent on the potato for food but which also produced an abundance of other food – was exacerbated by a host of political, social and economic factors which remain the subject of historical debate.

The Soviet famine of 1946–1947 was a major famine in the Soviet Union that lasted from mid-1946 to the winter of 1947 to 1948.

The R574 is an Irish regional road in the Beara peninsula which crosses the Caha Mountains via (Tim) Healy Pass. It runs from the R572 at Adrigole in County Cork to the R571 near Lauragh in County Kerry. It is a popular tourist route with the pass at an altitude of 300m giving panoramas towards Bantry Bay to the south-east and the Kenmare River to the north-west.

The British Association for the Relief of Distress in Ireland and the Highlands of Scotland, known as the British Relief Association (BRA), was a private charity of the mid-19th century in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Established by a group of prominent aristocrats, bankers and philanthropists in 1847, the charity was the largest private provider of relief during the Great Irish Famine and Highland Potato Famine of the 1840s. During its brief period of operation, the Association received donations and support from many notable politicians and royalty, including Queen Victoria.

The Irish Donation of 1676 is the name sometimes used to refer to a foreign aid consignment sent to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1676 from Ireland. A return donation 171 years later – from Massachusetts to Ireland – has been described as repayment for the original aid.

The islands of Newfoundland and Ireland, in addition to sharing similar northern latitudes and facing each other across the Atlantic Ocean, also had in common, during the middle of the 19th century, a heavy dependence on a single agricultural crop, the potato--a dependence that allowed the same blight that precipitated the Great Famine in Ireland to wreak havoc on this former British colony as well. Though acute, and the source of great suffering, the famine in Newfoundland lasted for fewer years than its Irish contemporary, which extended from 1845 to 1849. Beginning a year later, in 1846, it ended with the return to prosperity of the local fisheries in the spring and summer of 1848.

References

- ↑ Dwyer, Fin. "1925 – Ireland's Forgotten Famine and another government cover-up?".

- 1 2 "The Irish Famine: An Appeal for Funds". Sydney: Evening News. 12 February 1925. p. 10. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ↑ Ó Gráda, Cormac (November 2004). "Ireland's Great Famine: An Overview" (PDF). University College Dublin; Centre for Economic Research. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ↑ Dwyer, Fin. "1925 – Ireland's Forgotten Famine and another government cover-up?".

- ↑ "Ireland's forgotten famine of 1925". 14 April 2017.

- ↑ The Irish Times. 14 February 1925. p. 7.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ The Irish Times. 3 April 1925. p. 7.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ "Distressed Ireland". Hobart: The Mercury. 2 February 1925. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ↑ "Workers' Self Help: W.I.R. Organises Relief for Irish Famine Victims". Sydney: The Workers' Weekly. 19 June 1925. p. 3. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ↑ The Irish Times (14 February 1925), pp. 3, 9.

- ↑ The Irish Times (27 May 1925), p. 6.