Coke is a grey, hard, and porous fuel with a high carbon content and few impurities, made by heating coal or oil in the absence of air—a destructive distillation process. It is an important industrial product, used mainly in iron ore smelting, but also as a fuel in stoves and forges when air pollution is a concern.

Steelmaking is the process of producing steel from iron ore and/or scrap. In steelmaking, impurities such as nitrogen, silicon, phosphorus, sulfur and excess carbon are removed from the sourced iron, and alloying elements such as manganese, nickel, chromium, carbon and vanadium are added to produce different grades of steel. Limiting dissolved gases such as nitrogen and oxygen and entrained impurities in the steel is also important to ensure the quality of the products cast from the liquid steel.

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. Blast refers to the combustion air being "forced" or supplied above atmospheric pressure.

Anthracite iron or Anthracite 'Pig Iron' is the substance created by the smelting together of anthracite coal and iron ore, that is using Anthracite coal instead of charcoal to smelt iron ores — and was an important historic advance in the late-1830s enabling great acceleration the industrial revolution in Europe and North America.

A bloomery is a type of metallurgical furnace once used widely for smelting iron from its oxides. The bloomery was the earliest form of smelter capable of smelting iron. Bloomeries produce a porous mass of iron and slag called a bloom. The mix of slag and iron in the bloom, termed sponge iron, is usually consolidated and further forged into wrought iron. Blast furnaces, which produce pig iron, have largely superseded bloomeries.

A reverberatory furnace is a metallurgical or process furnace that isolates the material being processed from contact with the fuel, but not from contact with combustion gases. The term reverberation is used here in a generic sense of rebounding or reflecting, not in the acoustic sense of echoing.

An ironworks or iron works is an industrial plant where iron is smelted and where heavy iron and steel products are made. The term is both singular and plural, i.e. the singular of ironworks is ironworks.

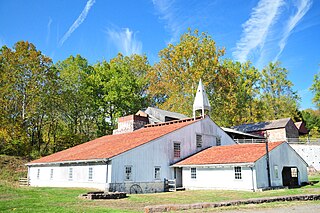

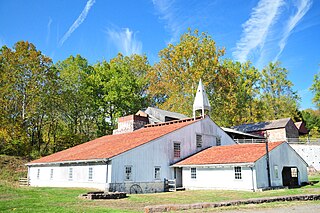

Hopewell Furnace National Historic Site in southeastern Berks County, near Elverson, Pennsylvania, is an example of an American 19th century rural "iron plantation," whose operations were based around a charcoal-fired cold-blast iron blast furnace. The significant restored structures include the furnace group (blast furnace, water wheel, blast machinery, cast house and charcoal house), as well as the ironmaster's house, a company store, the blacksmith's shop, a barn and several worker's houses.

Seend Ironstone Quarry and Road Cutting is a 3 acres (1.2 ha) Geological Site of Special Scientific Interest at Seend in Wiltshire, England, notified in 1965. The site contains facies of Lower Greensand containing specimens of fauna not found elsewhere.

Ferrous metallurgy, the metallurgy of iron and its alloys, began in prehistory. The earliest surviving iron artifacts, from the 4th millennium BC in Egypt, were made from meteoritic iron-nickel. It is not known when or where the smelting of iron from ores began, but by the end of the 2nd millennium BC iron was being produced from iron ores from at least Greece to India, and Sub-Saharan Africa. The use of wrought iron was known by the 1st millennium BC, and its spread defined the Iron Age. During the medieval period, smiths in Europe found a way of producing wrought iron from cast iron using finery forges. All these processes required charcoal as fuel.

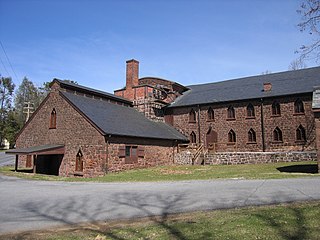

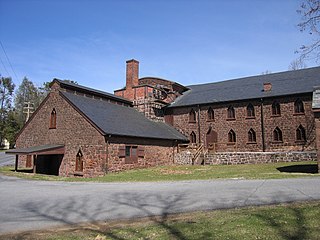

Cornwall Iron Furnace is a designated National Historic Landmark that is administered by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission in Cornwall, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania in the United States. The furnace was a leading Pennsylvania iron producer from 1742 until it was shut down in 1883. The furnaces, support buildings and surrounding community have been preserved as a historical site and museum, providing a glimpse into Lebanon County's industrial past. The site is the only intact charcoal-burning iron blast furnace in its original plantation in the western hemisphere. Established by Peter Grubb in 1742, Cornwall Furnace was operated during the Revolution by his sons Curtis and Peter Jr. who were major arms providers to George Washington. Robert Coleman acquired Cornwall Furnace after the Revolution and became Pennsylvania's first millionaire. Ownership of the furnace and its surroundings was transferred to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in 1932.

Charcoal iron is the substance created by the smelting of iron ore with charcoal.

The Grubb Family Iron Dynasty was a succession of iron manufacturing enterprises owned and operated by Grubb family members for more than 165 years. Collectively, they were Pennsylvania's leading iron manufacturer between 1840 and 1870.

In 2014, the United States was the world’s third-largest producer of raw steel, and the sixth-largest producer of pig iron. The industry produced 29 million metric tons of pig iron and 88 million tons of steel. Most iron and steel in the United States is now made from iron and steel scrap, rather than iron ore. The United States is also a major importer of iron and steel, as well as iron and steel products.

The US iron and steel industry has paralleled the industry in other countries in technological developments. In the 1800s, the US switched from charcoal to coke in ore smelting, adopted the Bessemer process, and saw the rise of very large integrated steel mills. In the 20th century, the US industry successively adopted the open hearth furnace, then the basic oxygen steelmaking process. Since the American industry peaked in the 1940s and 1950s, the US industry has shifted to small mini-mills and specialty mills, using iron and steel scrap as feedstock, rather than iron ore.

The Bonawe Iron Furnace, was an industrial complex located in Bonawe, Lorn District, Scotland. It operated in the middle of the eighteenth century, with the aim of producing pig iron. Central to this complex was a charcoal fired blast furnace.

The Bogolong iron mine and blast furnace is an abandoned iron mining and smelting site, near Bookham, New South Wales, Australia. Located in an area known best for sheep grazing and wool, it has been called Australia's 'forgotten furnace'. In 1874, the blast furnace produced a small amount of pig iron—sufficient to allow its testing—that was smelted from iron ore mined nearby. Plans to operate commercially did not eventuate. It is significant as one of the only three remaining ruins of 19th-Century iron-smelting blast furnaces in Australia, and the only one in New South Wales.

The British and Tasmanian Charcoal Iron Company (BTCIC) was an iron mining and smelting company that operated from 1874 to 1878 in Northern Tasmania, Australia. It was formed by floating the operations of a private company, the Tasmanian Charcoal Iron Company that operated between 1871 and 1874.

The Wundowie charcoal iron and wood distillation plant manufactured pig iron between 1948 and 1981 and wood distillation products between 1950 and 1977, at Wundowie, Western Australia.

The South Australian Iron and Steel Company, officially South Australian Iron and Steel Company Limited, was a colonial era iron-making venture, located in the Hindmarsh Tiers, near Mount Jagged, in the upper reaches of the Hindmarsh River valley, South Australia. Its blast furnace operated intermittently, over the period from 16 July to 5 December 1874.