Related Research Articles

The Galilean moons, or Galilean satellites, are the four largest moons of Jupiter: Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. They are the most readily visible Solar System objects after Saturn, the dimmest of the classical planets; though their closeness to bright Jupiter makes naked-eye observation very difficult, they are readily seen with common binoculars, even under night sky conditions of high light pollution. The invention of the telescope enabled the discovery of the moons in 1610. Through this, they became the first Solar System objects discovered since humans have started tracking the classical planets, and the first objects to be found to orbit any planet beyond Earth.

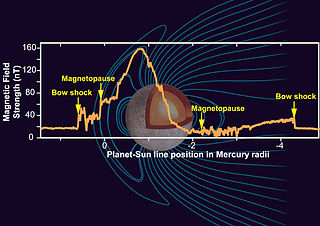

Mercury is the first planet from the Sun and the smallest in the Solar System. In English, it is named after the ancient Roman god Mercurius (Mercury), god of commerce and communication, and the messenger of the gods. Mercury is classified as a terrestrial planet, with roughly the same surface gravity as Mars. The surface of Mercury is heavily cratered, as a result of countless impact events that have accumulated over billions of years. Its largest crater, Caloris Planitia, has a diameter of 1,550 km (960 mi) and one-third the diameter of the planet. Similarly to the Earth's Moon, Mercury's surface displays an expansive rupes system generated from thrust faults and bright ray systems formed by impact event remnants.

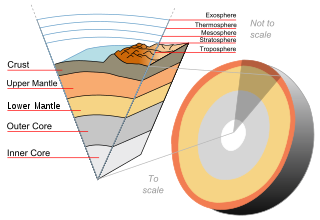

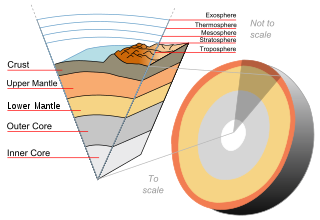

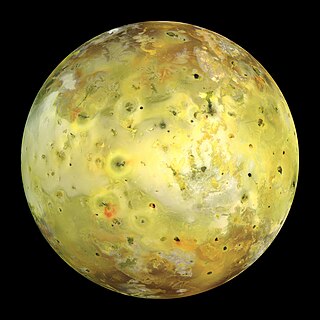

A terrestrial planet, telluric planet, or rocky planet, is a planet that is composed primarily of silicate, rocks or metals. Within the Solar System, the terrestrial planets accepted by the IAU are the inner planets closest to the Sun: Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars. Among astronomers who use the geophysical definition of a planet, two or three planetary-mass satellites – Earth's Moon, Io, and sometimes Europa – may also be considered terrestrial planets. The large rocky asteroids Pallas and Vesta are sometimes included as well, albeit rarely. The terms "terrestrial planet" and "telluric planet" are derived from Latin words for Earth, as these planets are, in terms of structure, Earth-like. Terrestrial planets are generally studied by geologists, astronomers, and geophysicists.

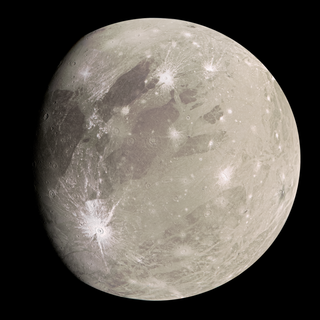

Ganymede, or Jupiter III, is the largest and most massive natural satellite of Jupiter and in the Solar System. It is the largest Solar System object without a substantial atmosphere, despite being the only moon in the Solar System with a substantial magnetic field. Like Titan, Saturn's largest moon, it is larger than the planet Mercury, but has somewhat less surface gravity than Mercury, Io, or the Moon due to its lower density compared to the three.

Geophysics is a subject of natural science concerned with the physical processes and physical properties of the Earth and its surrounding space environment, and the use of quantitative methods for their analysis. Geophysicists, who usually study geophysics, physics, or one of the Earth sciences at the graduate level, complete investigations across a wide range of scientific disciplines. The term geophysics classically refers to solid earth applications: Earth's shape; its gravitational, magnetic fields, and electromagnetic fields ; its internal structure and composition; its dynamics and their surface expression in plate tectonics, the generation of magmas, volcanism and rock formation. However, modern geophysics organizations and pure scientists use a broader definition that includes the water cycle including snow and ice; fluid dynamics of the oceans and the atmosphere; electricity and magnetism in the ionosphere and magnetosphere and solar-terrestrial physics; and analogous problems associated with the Moon and other planets.

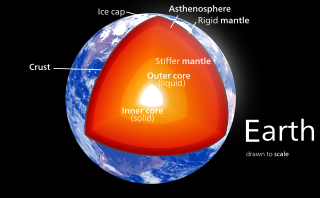

Earth's outer core is a fluid layer about 2,260 km (1,400 mi) thick, composed of mostly iron and nickel that lies above Earth's solid inner core and below its mantle. The outer core begins approximately 2,889 km (1,795 mi) beneath Earth's surface at the core-mantle boundary and ends 5,150 km (3,200 mi) beneath Earth's surface at the inner core boundary.

In planetary science, planetary differentiation is the process by which the chemical elements of a planetary body accumulate in different areas of that body, due to their physical or chemical behavior. The process of planetary differentiation is mediated by partial melting with heat from radioactive isotope decay and planetary accretion. Planetary differentiation has occurred on planets, dwarf planets, the asteroid 4 Vesta, and natural satellites.

In physics, the dynamo theory proposes a mechanism by which a celestial body such as Earth or a star generates a magnetic field. The dynamo theory describes the process through which a rotating, convecting, and electrically conducting fluid can maintain a magnetic field over astronomical time scales. A dynamo is thought to be the source of the Earth's magnetic field and the magnetic fields of Mercury and the Jovian planets.

A planetary core consists of the innermost layers of a planet. Cores may be entirely liquid, or a mixture of solid and liquid layers as is the case in the Earth. In the Solar System, core sizes range from about 20% to 85% of a planet's radius (Mercury).

Io, or Jupiter I, is the innermost and second-smallest of the four Galilean moons of the planet Jupiter. Slightly larger than Earth's moon, Io is the fourth-largest moon in the Solar System, has the highest density of any moon, the strongest surface gravity of any moon, and the lowest amount of water by atomic ratio of any known astronomical object in the Solar System. It was discovered in 1610 by Galileo Galilei and was named after the mythological character Io, a priestess of Hera who became one of Zeus's lovers.

The geology of Mercury is the scientific study of the surface, crust, and interior of the planet Mercury. It emphasizes the composition, structure, history, and physical processes that shape the planet. It is analogous to the field of terrestrial geology. In planetary science, the term geology is used in its broadest sense to mean the study of the solid parts of planets and moons. The term incorporates aspects of geophysics, geochemistry, mineralogy, geodesy, and cartography.

The geology of Venus is the scientific study of the surface, crust, and interior of the planet Venus. Within the Solar System, it is the one nearest to Earth and most like it in terms of mass, but has no magnetic field or recognizable plate tectonic system. Much of the ground surface is exposed volcanic bedrock, some with thin and patchy layers of soil covering, in marked contrast with Earth, the Moon, and Mars. Some impact craters are present, but Venus is similar to Earth in that there are fewer craters than on the other rocky planets that are largely covered by them. This is due in part to the thickness of the Venusian atmosphere disrupting small impactors before they strike the ground, but the paucity of large craters may be due to volcanic re-surfacing, possibly of a catastrophic nature. Volcanism appears to be the dominant agent of geological change on Venus. Some of the volcanic landforms appear to be unique to the planet. There are shield and composite volcanoes similar to those found on Earth, although these volcanoes are significantly shorter than those found on Earth or Mars. Given that Venus has approximately the same size, density, and composition as Earth, it is plausible that volcanism may be continuing on the planet today, as demonstrated by recent studies.

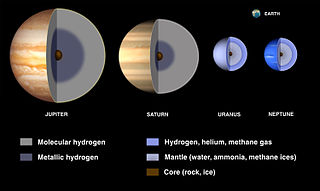

An ice giant is a giant planet composed mainly of elements heavier than hydrogen and helium, such as oxygen, carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur. There are two ice giants in the Solar System: Uranus and Neptune.

Earth's inner core is the innermost geologic layer of the planet Earth. It is primarily a solid ball with a radius of about 1,220 km (760 mi), which is about 20% of Earth’s radius or 70% of the Moon's radius.

The magnetosphere of Jupiter is the cavity created in the solar wind by Jupiter's magnetic field. Extending up to seven million kilometers in the Sun's direction and almost to the orbit of Saturn in the opposite direction, Jupiter's magnetosphere is the largest and most powerful of any planetary magnetosphere in the Solar System, and by volume the largest known continuous structure in the Solar System after the heliosphere. Wider and flatter than the Earth's magnetosphere, Jupiter's is stronger by an order of magnitude, while its magnetic moment is roughly 18,000 times larger. The existence of Jupiter's magnetic field was first inferred from observations of radio emissions at the end of the 1950s and was directly observed by the Pioneer 10 spacecraft in 1973.

The exploration of Mercury has a minor role in the space interests of the world. It is the least explored inner planet. As of 2015, the Mariner 10 and MESSENGER missions have been the only missions that have made close observations of Mercury. MESSENGER made three flybys before entering orbit around Mercury. A third mission to Mercury, BepiColombo, a joint mission between the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) and the European Space Agency, is to include two probes. MESSENGER and BepiColombo are intended to gather complementary data to help scientists understand many of the mysteries discovered by Mariner 10's flybys.

The history of scientific thought about the formation and evolution of the Solar System began with the Copernican Revolution. The first recorded use of the term "Solar System" dates from 1704. Since the seventeenth century, philosophers and scientists have been forming hypotheses concerning the origins of our Solar System and the Moon and attempting to predict how the Solar System would change in the future. René Descartes was the first to hypothesize on the beginning of the Solar System; however, more scientists joined the discussion in the eighteenth century, forming the groundwork for later hypotheses on the topic. Later, particularly in the twentieth century, a variety of hypotheses began to build up, including the now-commonly accepted nebular hypothesis.

Mercury's magnetic field is approximately a magnetic dipole apparently global, on planet Mercury. Data from Mariner 10 led to its discovery in 1974; the spacecraft measured the field's strength as 1.1% that of Earth's magnetic field. The origin of the magnetic field can be explained by dynamo theory. The magnetic field is strong enough near the bow shock to slow the solar wind, which induces a magnetosphere.

Comparative planetary science or comparative planetology is a branch of space science and planetary science in which different natural processes and systems are studied by their effects and phenomena on and between multiple bodies. The planetary processes in question include geology, hydrology, atmospheric physics, and interactions such as impact cratering, space weathering, and magnetospheric physics in the solar wind, and possibly biology, via astrobiology.

Over the years, our ability to detect, confirm, and characterize exoplanets and their atmospheres has improved, allowing researchers to begin constraining exoplanet interior composition and structure. While most exoplanet science is focused on exoplanetary atmospheric environments, the mass and radius of a planet can tell us about a planet's density, and hence, its internal processes. The internal processes of a planet are partly responsible for its atmosphere, and so they are also a determining factor in a planet's capacity to support life.

References

- ↑ Angelo Pio Rossi; Stephan van Gasselt (28 November 2017). Planetary Geology. Springer. p. 238. ISBN 978-3-319-65179-8.

- ↑ "Iron 'snow' helps maintain Mercury's magnetic field, scientists say". 8 May 2008.