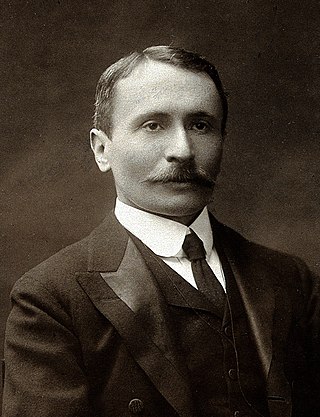

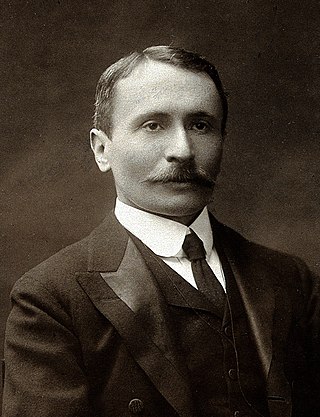

Sir Marc Aurel Stein, (Hungarian: Stein Márk Aurél; 26 November 1862 – 26 October 1943) was a Hungarian-born British archaeologist, primarily known for his explorations and archaeological discoveries in Central Asia. He was also a professor at Indian universities.

The Kharoṣṭhī script, also known as the Gāndhārī script, was an ancient Indic script used by various peoples from the north-western outskirts of the Indian subcontinent to Central Asia via Afghanistan. An abugida, it was introduced at least by the middle of the 3rd century BCE, possibly during the 4th century BCE, and remained in use until it died out in its homeland around the 3rd century CE.

Augustus Frederic Rudolf Hoernlé CIE, also referred to as Rudolf Hoernle or A. F. Rudolf Hoernle, was a German Indologist and philologist. He is famous for his studies on the Bower Manuscript (1891), Weber Manuscript (1893) and other discoveries in northwestern China and Central Asia particularly in collaboration with Aurel Stein. Born in India to a Protestant missionary family from Germany, he completed his education in Switzerland, and studied Sanskrit in the United Kingdom. He returned to India, taught at leading universities there, and in the early 1890s published a series of seminal papers on ancient manuscripts, writing scripts and cultural exchange between India, China and Central Asia. His collection after 1895 became a victim of forgery by Islam Akhun and colleagues in Central Asia, a forgery revealed to him in 1899. He retired from the Indian office in 1899 and settled in Oxford, where he continued to work through the 1910s on archaeological discoveries in Central Asia and India. This is now referred to as the "Hoernle collection" at the British Library.

The Bower Manuscript is a collection of seven fragmentary Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit treatises found buried in a Buddhist memorial stupa near Kucha, northwestern China. Written in early Gupta script on birch bark, it is variously dated in 5th to early 6th century. The Bower manuscript includes the oldest dated fragments of an Indian medical text, the Navanitaka.

Hotan or Khotan is a major oasis town in southwestern Xinjiang, an autonomous region in Northwestern China. The city proper of Hotan broke off from the larger Hotan County to become an administrative area in its own right in August 1984. It is the seat of Hotan Prefecture.

The Kingdom of Khotan was an ancient Buddhist Saka kingdom located on the branch of the Silk Road that ran along the southern edge of the Taklamakan Desert in the Tarim Basin. The ancient capital was originally sited to the west of modern-day Hotan at Yotkan. From the Han dynasty until at least the Tang dynasty it was known in Chinese as Yutian. This largely Buddhist kingdom existed for over a thousand years until it was conquered by the Muslim Kara-Khanid Khanate in 1006, during the Islamization and Turkicization of Xinjiang.

The Tarim Basin is an endorheic basin in Xinjiang, Northwestern China occupying an area of about 888,000 km2 (343,000 sq mi) and one of the largest basins in Northwest China. Located in China's Xinjiang region, it is sometimes used synonymously to refer to the southern half of the province, that is, Southern Xinjiang or Nanjiang, as opposed to the northern half of the province known as Dzungaria or Beijiang. Its northern boundary is the Tian Shan mountain range and its southern boundary is the Kunlun Mountains on the edge of the Tibetan Plateau. The Taklamakan Desert dominates much of the basin. The historical Uyghur name for the Tarim Basin is Altishahr, which means 'six cities' in Uyghur. The region was also called Little Bukhara or Little Bukharia.

James Prinsep was an English scholar, orientalist and antiquary. He was the founding editor of the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal and is best remembered for deciphering the Kharosthi and Brahmi scripts of ancient India. He studied, documented and illustrated many aspects of numismatics, metallurgy, meteorology apart from pursuing his career in India as an assay master at the mint in Benares.

Saka, or Sakan, was a variety of Eastern Iranian languages, attested from the ancient Buddhist kingdoms of Khotan, Kashgar and Tumshuq in the Tarim Basin, in what is now southern Xinjiang, China. It is a Middle Iranian language. The two kingdoms differed in dialect, their speech known as Khotanese and Tumshuqese.

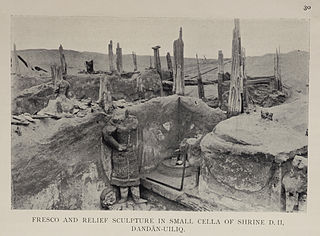

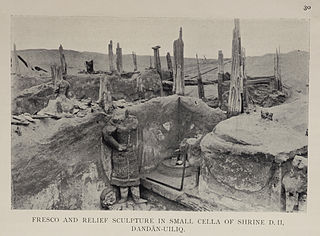

Dandan Oilik, also Dandān-Uiliq, lit. "the houses with ivory", is an abandoned historic oasis town and Buddhist site in the Taklamakan Desert of China, located to the northeast of Khotan in what is now the autonomous region of Xinjiang, between the Khotan and Keriya rivers. The central site covers an area of 4.5 km2; the greater oasis extends over an area of 22 km2. The site flourished from the sixth century as a site along the southern branch of the Silk Road until its abandonment before the Tibetan advance at the end of the eighth century.

The Niya ruins, is an archaeological site located about 115 km (71 mi) north of modern Niya Town on the southern edge of the Tarim Basin in modern-day Xinjiang, China. The ancient site was known in its native language as Caḍ́ota, and in Chinese during the Han dynasty as Jingjue. Numerous ancient archaeological artifacts have been uncovered at the site.

The International Dunhuang Project (IDP) is an international collaborative effort to conserve, catalogue and digitise manuscripts, printed texts, paintings, textiles and artefacts from the Mogao caves at the Western Chinese city of Dunhuang and various other archaeological sites at the eastern end of the Silk Road. The project was established by the British Library in 1994, and now includes twenty-two institutions in twelve countries. As of 18 February 2021 the online IDP database comprised 143,290 catalogue entries and 538,821 images. Most of the manuscripts in the IDP database are texts written in Chinese, but more than fifteen different scripts and languages are represented, including Brahmi, Kharosthi, Khotanese, Sanskrit, Tangut, Tibetan, Tocharian and Old Uyghur.

Buddhism in Khotan comprised bodies of Buddhist religious doctrine and institutions characteristic of the Iranic Kingdom of Khotan as well as much of Western China and Tajikistan. It was the state religion of the Kingdom of Khotan until its collapse in 1000. The dominant school of Buddhism in Khotan was the Mahāsāṃghika school - from which the Mahayana and Vajrayana schools would develop. The kingdom's vast collection of texts, which included the indigenous Book of Zambasta and a Khotanese translation of the Sanghata Sutra, helped Khotan influence the Buddhist practices of its neighbors, most notably Tibet.

Balawaste is an archaeological site in the eastern part of the Khotan oasis, near the village of Domoko on the southern arm of the Silk Road. It included a small room, an animal pen and a Buddhist shrine.

Mazar Tagh is the site of a ruined hill fort in the middle of the Taklamakan desert, dating from the time of the Tibetan Empire. Like the Miran fort site, its excavation has yielded hundreds of military documents from the 8th and 9th century, which are among the earliest surviving Tibetan manuscripts, and vital sources for understanding the early history of Tibet. The site is now located north of the modern city of Hotan in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region of the People's Republic of China.

Rawak is a Buddhist stupa located on the southern rim of the Taklamakan Desert in Xinjiang, China, along the famous trade route known as the Silk Road in the first millennium Kingdom of Khotan. Around the stupa there are other smaller structures which were originally decorated with a large number of colossal statues. The courtyard of the temple was surrounded by a wall, which contained terracotta relieves and some wall-paintings. The stupa and other structures form a three-dimensional mandala. The site is now about 40 km north of the modern city of Hotan in Xinjiang Autonomous Region, China.

Miran fort aka "Ruins of Milan" (米兰古城遗址) is a ruined defensive structure in Miran, Xinjiang, China. The fort was active during the Tibetan Empire, in the 8th and 9th centuries AD. It is similar in structure to the fort at Mazar Tagh, which was also used by the Tibetan army in the same period. Like the Mazar Tagh site, the excavation of the fort at Miran has yielded hundreds of military documents from the 8th and 9th century, which are among the earliest surviving Tibetan manuscripts, and vital sources for understanding the early history of Tibet.

The concept of the Silk Road has fascinated Europeans for more than a century, symbolizing the exchange between the West and the East since Antiquity. However, the issue of what route was followed by it was not an easy one to resolve. The first person to explore this in detail was Aurel Stein, coming from the west through Kashgar and entering the Taklamakan desert in September 1900, before heading south to Khotan on his first expedition to Serindia. Stein was to come back several times, extending his research area to increase the known sites along the Silk Road in this region.

The Weber Manuscript, also called Weber Manuscripts, is a collection of nine, possibly eleven, incomplete ancient Indian treatises written mostly in classical Sanskrit that were found buried within a Buddhist monument in northwestern China in late 19th-century. It is named after the Moravian missionary F. Weber who acquired the set from an Afghani merchant in Ladakh, and then forwarded it to the German Indologist and philologist Rudolf Hoernlé in Calcutta. The manuscripts consist of 76 page-leaves, written in Northwestern Gupta and Central Asian Nagari scripts. They were copied before the end of 7th-century, likely in the 5th-century or the 6th–century. The original texts that were copied to produce these manuscripts were likely considerably older Indian texts, at least one between 3rd-century BCE and pre-2nd-century CE. The Weber Manuscript is notable for having been written on two types of paper – Central Asian and Nepalese, attesting to the spread of paper technology outside of interior China and its use for Indian religious texts by the 5th– or 6th-century.

The Lumbini pillar inscription, also called the Paderia inscription, is an inscription in the ancient Brahmi script, discovered in December 1896 on a pillar of Ashoka in Lumbini, Nepal by former Chief of the Nepalese Army General Khadga Shamsher Jang Bahadur Rana under the authority of Nepalese government and assisted by Alois Anton Führer. Another famous inscription discovered nearby in a similar context is the Nigali-Sagar inscription. The Lumbini inscription is generally categorized among the Minor Pillar Edicts of Ashoka, although it is in the past tense and in the ordinary third person, suggesting that it is not a pronouncement of Ashoka himself, but a rather later commemoration of his visit in the area.