Writings

Clark began as a leading revisionist historian of 17th- and 18th- century British history. He is known for arguing against both the Marxist and Whiggish interpretations of the late 17th and 18th centuries. Instead, Clark emphasises the unities and coherences of the period between 1660 and 1832. It was he who dubbed it the "long eighteenth century", a periodisation that is now widely accepted in historical academia. [1] Clark maintains the period was one of Anglican-aristocratic hegemony, marked by popular acceptance of the monarchy and the Church of England as symbols of national unity. This edifice was characterised by the dominance of an aristocratic-gentry oligarchy and a sense of national identity (preceding 19th-century nationalism), which was firmly underpinned by a shared history and religious allegiance. In Clark's model, Britons embraced the official entrenchment of these parameters, which was challenged primarily by religious dissent.

In his first work, The Dynamics of Change, Clark attempted to explain how the two-party system of Queen Anne's reign, described by Geoffrey Holmes in British Politics in the Age of Anne, was transformed into the more fluid system of George III's reign that was uncovered by Lewis Namier in The Structure of Politics at the Accession of George III . [2] Clark argued that the Tory and Whig parties survived Anne's death in 1714 until the political crisis of March 1754 – June 1757 caused the realignment of British politics, which produced the political groupings that George III inherited in 1760. [2]

Clark's Revolution and Rebellion, published in 1986, is a study of the historiography of 17th- and 18th- century English history. He categorised historians into "Old Hat" (Whig–Liberal), "Old Guard" (Marxist), and "Class of '68" (modern radical) schools, all of whom he criticised as mistaken. [3] Clark reiterated his belief in the central position of religion in the conflicts of these centuries: he argued that it was those who cared most about religion who had caused Parliament to play a more active role in the years before the Civil War. [4] Jacobitism, in Clark's view, was important in the 18th century because it was the only realistic (because it was non-secular) alternative to Hanoverian rule. The disappearance of the Jacobite alternative during the Seven Years' War, Clark maintained, led to the consolidation of the Anglican and monarchic confessional state. [4]

In his 1993 work, The Language of Liberty, 1660–1832, Clark reinterpreted the American Revolution as America's first civil war and the West's last war of religion. [5] The Revolution, Clark asserted, was triggered by the denominational conflicts still endemic at that time within the English-speaking North Atlantic world. [6]

Clark has frequently maintained that too often the 18th century has been interpreted teleologically in the light of the 19th century; he sees his mission as an historian to explain the long 18th century in its own terms. Clark criticised Marxists such as Christopher Hill, Eric Hobsbawm, and E.P. Thompson for advancing what he argued was an incorrect interpretation. Styled by Ronald Hutton as a "political and religious reactionary", [7] Clark criticised Hill, Hobsbawm, and Thompson for advancing what he derided as an incorrect interpretation. In 1985, Clark called Hill, Hobsbawm, and Thompson "that cohort of scholars whose minds were formed in the matrix of inter-war Marxism". [8]

Clark became known for his attacks in the 1980s on Sir John H. Plumb, which made him certainly conspicuous and according to Hutton "probably the most hated living historian". [9] A letter defending Plumb was published and signed by every history professor at Cambridge except for Sir Geoffrey Elton. [10] Portions of Clark's work, however, were accepted by his colleagues (though perhaps as exaggerated) and several of them felt compelled to concede that he "had performed a valuable service in drawing attention to important features of eighteenth-century society, particularly the religious element, which had hitherto been neglected". [10]

In 1994, Clark published Samuel Johnson: Literature, Religion, and English Cultural Politics from the Restoration to Romanticism, in which he argued that Johnson was not only a Tory but also a Jacobite and a nonjuror (one who declined or avoided loyalty oaths to the Hanoverians). The thesis proved controversial. Clark and the Cambridge-based literary scholar Howard Erskine-Hill debated American literary scholars, chiefly Donald Greene and Howard Weinbrot, in two successive volumes of The Age of Johnson (Volumes 7 and 8) and an issue of Studies in English Literature. Clark and Erskine-Hill produced an edited volume on Johnson's political views in 2002 and two additional volumes on the subject in 2012.

Jacobitism was a political movement that supported the restoration of the senior line of the House of Stuart to the British throne. The name derives from the first name of James II and VII, which in Latin translates as Jacobus. When James went into exile after the November 1688 Glorious Revolution, the Parliament of England argued that he had abandoned the English throne, which they offered to his Protestant daughter Mary II, and her husband William III. In April, the Scottish Convention held that he "forfeited" the throne of Scotland by his actions, listed in the Articles of Grievances.

The Scottish Enlightenment was the period in 18th- and early-19th-century Scotland characterised by an outpouring of intellectual and scientific accomplishments. By the eighteenth century, Scotland had a network of parish schools in the Scottish Lowlands and five universities. The Enlightenment culture was based on close readings of new books, and intense discussions took place daily at such intellectual gathering places in Edinburgh as The Select Society and, later, The Poker Club, as well as within Scotland's ancient universities.

The Kingdom of Ireland was a monarchy on the island of Ireland that was a client state of England and then of Great Britain. It existed from 1542 until 1801. It was ruled by the monarchs of England and then of Great Britain, and administered from Dublin Castle by a viceroy appointed by the English king: the Lord Deputy of Ireland. It had a parliament, composed of Anglo-Irish and native nobles. From 1661 until 1801, the administration controlled an army. A Protestant state church, the Church of Ireland, was established. Although styled a kingdom, for most of its history it was, de facto, an English dependency. This status was enshrined in Poynings' Law and in the Declaratory Act of 1719.

John Edward Christopher Hill was an English Marxist historian and academic, specialising in 17th-century English history. From 1965 to 1978 he was Master of Balliol College, Oxford.

Roy Sydney Porter, FBA was a British historian known for his work on the history of medicine. He retired in 2001 from the director of the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine at University College London (UCL).

The long nineteenth century is a term for the 125-year period beginning with the onset of the French Revolution in 1789 and ending with the outbreak of World War I in 1914. It was coined by Russian writer Ilya Ehrenburg and British Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm. The term refers to the notion that the period reflects a progression of ideas which are characteristic to an understanding of the 19th century in Europe.

Historiography is the study of how history is written. One pervasive influence upon the writing of history has been nationalism, a set of beliefs about political legitimacy and cultural identity. Nationalism has provided a significant framework for historical writing in Europe and in those former colonies influenced by Europe since the nineteenth century. Typically official school textbooks are based on the nationalist model and focus on the emergence, trials and successes of the forces of nationalism.

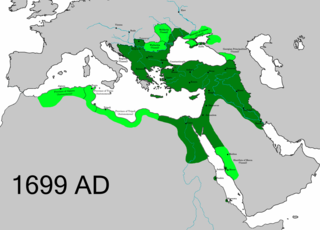

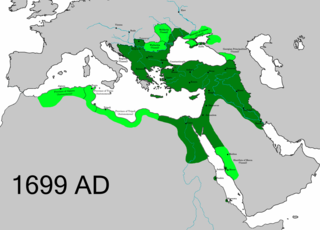

The history of the Ottoman Empire in the 18th century has classically been described as one of stagnation and reform. In analogy with 18th-century France, it is also known as the Ancien Régime or Old Regime, contrasting with the "New Regime" of the Nizam-i Cedid and Tanzimat in the 19th century.

Jeremy Black is a British historian, writer, and former professor of history at the University of Exeter. He is a senior fellow at the Center for the Study of America and the West at the Foreign Policy Research Institute in Philadelphia, US.

Eveline Cruickshanks was an historian of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century British political history, specialising in Jacobitism and Toryism. She was of English, Scottish and French descent. She was an Honorary Fellow of the Institute of Historical Research of the University of London.

Harry Thomas Dickinson FRSE is an English historian specialising in British eighteenth century politics. He obtained his BA and MA from the University of Durham and his PhD from the University of Newcastle upon Tyne. He was Reader in History and later Richard Lodge Professor of British History at the University of Edinburgh. He was editor of the journal History from 1993 to 2000. Isaac Kramnick wrote that of the biographies of Lord Bolingbroke, Dickinson's was the "most reliable". In the opinion of David Armitage, Dickinson's life of Lord Bolingbroke "replaced all earlier accounts".

Scottish religion in the eighteenth century includes all forms of religious organisation and belief in Scotland in the eighteenth century. This period saw the beginnings of a fragmentation of the Church of Scotland that had been created in the Reformation and established on a fully Presbyterian basis after the Glorious Revolution. These fractures were prompted by issues of government and patronage, but reflected a wider division between the Evangelicals and the Moderate Party. The legal right of lay patrons to present clergymen of their choice to local ecclesiastical livings led to minor schisms from the church. The first in 1733, known as the First Secession and headed by figures including Ebenezer Erskine, led to the creation of a series of secessionist churches. The second in 1761 led to the foundation of the independent Relief Church.

Social revolutions are sudden changes in the structure and nature of society. These revolutions are usually recognized as having transformed society, economy, culture, philosophy, and technology along with but more than just the political systems.

A counter-revolutionary or an anti-revolutionary is anyone who opposes or resists a revolution, particularly one who acts after a revolution in order to try to overturn it or reverse its course, in full or in part. The adjective "counter-revolutionary" pertains to movements that would restore the state of affairs, or the principles, that prevailed during a prerevolutionary era.

William Hamilton Reid was a British poet and hack writer. A supporter of radical politics turned loyalist, he is known for his 1800 pamphlet exposé The Rise and Dissolution of the Infidel Societies in this Metropolis. His later views turned again towards radicalism.

Maureen Wall was an Irish historian with a focus on the 18th century. She is regarded as pioneer of modern studies of the Penal Laws in Ireland.

A Discourse on the Love of Our Country is a speech and pamphlet delivered by Richard Price in England in 1789, in support of the French Revolution, equating it with the Glorious Revolution a century earlier in England. This set off the Revolution Controversy, an exchange of arguments via pamphlet between those supporting or opposing the idea of the French Revolution.

John Jebb was an Irish Anglican priest in the second half of the 18th century.

The Gottschalk Prize is awarded for an outstanding historical or critical study on the 18th century and carries a prize of US$1,000. It is named in honour of Louis Gottschalk (1899–1975), second President of the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies (ASECS), President of the American Historical Association, and for many years Distinguished Service Professor at the University of Chicago. His scholarship exemplified the humanistic ideals that this award is meant to encourage.

Greg Clingham is a British literary scholar and publisher. He was Professor of English (2001–18) at Bucknell University, Pennsylvania, where he held the NEH Chair in the Humanities (1996–99) and the John P. Crozer Chair of English Literature (2011–16). He was for twenty-three years, the director of Bucknell University Press (1996-2018).