Related Research Articles

The Japanese missions to Imperial China were diplomatic embassies which were intermittently sent to the Chinese imperial court. Any distinction amongst diplomatic envoys sent from the Japanese court or from any of the Japanese shogunates was lost or rendered moot when the ambassador was received in the Chinese capital.

The word Japan is an exonym, and is used by many languages. The Japanese names for Japan are Nihon and Nippon. They are both written in Japanese using the kanji 日本.

Ono no Imoko was a Japanese politician and diplomat in the late 6th and early 7th century, during the Asuka period.

Taihō (大宝) was a Japanese era name after a late 7th century interruption in the sequence of nengō after Shuchō and before Keiun. This period spanned the years from March 701 through May 704. The reigning emperor was Monmu-tennō (文武天皇).

Fujiwara no Umakai was a Japanese statesman, courtier, general and politician during the Nara period. The third son of Fujiwara no Fuhito, he founded the Shikike ("Ceremonials") branch of the Fujiwara clan.

Takamuko no Kuromaro was a Japanese scholar and diplomat of the Asuka period.

The Ningbo incident was a 1523 brawl between trade representatives of two Japanese daimyō clans — the Ōuchi and the Hosokawa — in the Ming Chinese city of Ningbo. The Ōuchi pillaged and harmed local residents, causing massive damage. The turmoil resulted in the interruption of the Ming-Japanese trade and led to a surge in piratical (wokou) activity on the Chinese coast. The episode is also known by the names Ningbo tribute conflict (寧波争貢事件), Mingzhou incident (明州之亂), or the Sōsetsu incident (宗設之亂).

The Japanese missions to Tang China were Japanese efforts to learn Chinese culture and civilization from Tang China, in the 7th, 8th and 9th centuries. The nature of those contacts evolved gradually from political and ceremonial change into cultural exchanges, and the process accompanied growing commercial ties which developed over time.

Japanese missions to Ming China represent a lens for examining and evaluating the relationships between China and Japan in the 15th through the 17th centuries. The nature of these bilateral contacts encompassed political and ceremonial acknowledgment as well as cultural exchanges. The evolution of diplomatic ties accompanied the growing commercial ties which grew over time.

Kenchū Keimitsu (堅中圭密) was a Japanese Zen Buddhist monk and diplomat in the Muromachi period. He was the chief envoy of a mission sent by the Ashikaga shogunate to the court of the Yongle Emperor in Nanjing. He would return to China at the head of four subsequent missions to the Chinese Imperial court in Beijing.

Sakugen Shūryō was a Japanese Zen Buddhist monk, a poet and diplomat in the Muromachi period. He was the chief envoy of a 1547 mission sent by the Ashikaga shogunate to the court of the Jiajing Emperor in Beijing.

Ryōan Keigo was a Japanese Zen Buddhist monk and diplomat in the Muromachi period. He was the chief envoy of a 1511–1513 mission sent by the Ashikaga shogunate to the court of the Zhengde Emperor in Beijing.

Iki no Hakatoko was a Japanese diplomat, legal scholar and writer.

The tributary system of China, or Cefeng system at its height was a network of loose international relations centered around China which facilitated trade and foreign relations by acknowledging China's hegemonic role within a Sinocentric world order. It involved multiple relationships of trade, military force, diplomacy and ritual. The other states had to send a tributary envoy to China on schedule, who would kowtow to the Chinese emperor as a form of tribute, and acknowledge his superiority and precedence. The other countries followed China's formal ritual in order to keep the peace with the more powerful neighbor and be eligible for diplomatic or military help under certain conditions. Political actors within the tributary system were largely autonomous and in almost all cases virtually independent.

Japanese missions to Baekje represent an aspect of the international relations of mutual Baekje-Japanese contacts and communication. The bilateral exchanges were intermittent.

Japanese missions to Silla represent an aspect of the international relations of mutual Silla-Japanese contacts and communication. The bilateral exchanges were intermittent.

Genbō was a Japanese scholar-monk and bureaucrat of the Imperial Court at Nara. He is best known as a leader of the Hossō sect of Buddhism and as the adversary of Fujiwara no Hirotsugu.

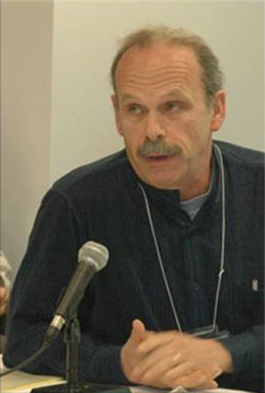

Joshua A. Fogel is an American-Canadian Sinologist, historian, and translator who specializes in the history of modern China, especially focusing on the cultural and political relations between China and Japan. He has held a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair at York University in Toronto since 2005. Before that he taught at Harvard University (1981-1988) and the University of California, Santa Barbara (1989-2005). He is a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada.

Shanghai has a Japanese expatriate group, particularly in the Gubei area of Changning District, which houses the majority of Japanese expatriates in Shanghai. Some Japanese follow the "Shanghai dream" where they spend several years in Shanghai to gain professional experience or knowledge of Mandarin Chinese, and either continue working in Shanghai or return to Japan later.

References

- Fogel, Joshua A. (2009). Articulating the Sinosphere: Sino-Japanese Relations in Space and Time. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674032590; OCLC 255142264

- Nussbaum, Louis Frédéric and Käthe Roth. (2005). Japan Encyclopedia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5; OCLC 48943301