Related Research Articles

Abductions of Japanese citizens from Japan by agents of the North Korean government took place during a period of six years from 1977 to 1983. Although only 17 Japanese are officially recognized by the Japanese government as having been abducted, there may have been hundreds of others. The North Korean government has officially admitted to abducting 13 Japanese citizens.

An estimated 84,532 South Koreans were taken to North Korea during the Korean War. In addition, South Korean statistics claim that, since the Korean Armistice Agreement in 1953, about 3,800 people have been abducted by North Korea, 489 of whom were still being held in 2006.

Koreans in Japan comprise ethnic Koreans who have permanent residency status in Japan or who have become Japanese citizens, and whose immigration to Japan originated before 1945, or who are descendants of those immigrants. They are a group distinct from South Korean nationals who have immigrated to Japan after the end of World War II and the division of Korea.

The human rights record of North Korea has been condemned, with the United Nations and groups such as Human Rights Watch all critical of it. Amnesty International considers North Korea to have no contemporary parallel with respect to violations of liberty.

The General Association of Korean Residents in Japan, abbreviated as Chongryon or Chōsen Sōren, is one of two main organisations for Zainichi Koreans, the other being Mindan. It has close ties to North Korea and functions as North Korea's de facto embassy in Japan, as there are no diplomatic relations between the two countries. The organisation is headquartered in Chiyoda, Tokyo, and there are prefectural and regional head offices and branches throughout Japan.

Kang Chol-hwan is a North Korean defector, author, and the founder and president of the North Korea Strategy Center.

Yodok concentration camp was a kwalliso in North Korea. The official name was Kwan-li-so No. 15. The camp was used to segregate those seen as enemies of the state, punish them for political misdemeanors, and put them to hard labour. It was closed down in 2014.

The Sŭnghori concentration camp was a labor camp for political prisoners which was located in North Hwanghae Province, North Korea, about 70 kilometers from Pyongyang.

The Man Gyong Bong 92 is a cargo-passenger ferry, named after a hill near Pyongyang. The ferry was built in 1992 with funds from Chongryon, the pro-North Korean General Association of Korean Residents in Japan, and was used to transport passengers and cargo between North Korea and Japan. These voyages continued until 2006 when Japan banned North Korean ships from its waters. In 2011 the ship trialed a route between Rason and Mount Kumgang. In 2018, the ship carried a 140 person delegation, as well as an art troupe, for the 2018 Winter Olympics and docked in Mukho port.

In the North Korean government, the Cabinet is the administrative and executive body. The North Korean government consists of three branches: administrative, legislative, and judicial. However, they are not independent of each other, but all branches are under the exclusive political leadership of the Workers' Party of Korea (WPK).

Jo Myong-rok was a North Korean military officer who held the military rank Chasu. In 1998, he was appointed first vice-chairman of the National Defence Commission of North Korea, Director of the Korean People's Army General Political Bureau. Previously, he was the commander of the air defence forces.

Kim Yong-chun was a North Korean soldier and politician. He was a leader of the North Korean military. He held the North Korean military rank Chasu, was Vice Chairman of the National Defense Commission of North Korea, and was Minister of People's Armed Forces. He held a minor post within the Workers Party.

Dear Pyongyang is a documentary film by Zainichi Korean director Yang Yong-hi about her family. It was shot in both Yang's hometown of Osaka, Japan, and Pyongyang, North Korea. The film has both Korean and Japanese dialogue with subtitles. The US release has Korean and Japanese dialogue with English subtitles. In August 2006, Yang released a book in Japanese under the same title expanding on the themes she explored in the film.

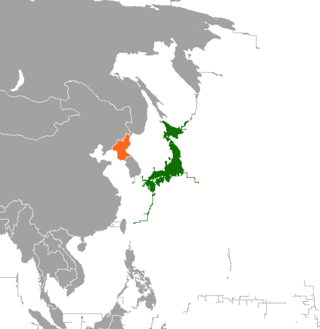

Japan–North Korea relations refers to international relations between Japan and North Korea. Relations between Japan and North Korea have never been formally established, but there have been diplomatic talks between the two governments to discuss the issue of kidnapped Japanese citizens and North Korea's nuclear program. Relations between the two countries are severely strained and marked by tension and hostility. According to a 2014 BBC World Service poll, 91% of Japanese people view North Korea's influence negatively, with just 1% expressing a positive view; the most negative perception of North Korea in the world.

The death of Kim Jong Il was reported by North Korean state television news on 19 December 2011. The presenter Ri Chun-hee announced that he had died on 17 December at 8:30 am of a massive heart attack while travelling by train to an area outside Pyongyang. Reportedly, he had received medical treatment for cardiac and cerebrovascular diseases, and during the trip, Kim was said to have had an "advanced acute myocardial infarction, complicated with a serious heart shock". However, it was reported in December 2012 by South Korean media that the heart attack had instead occurred in a fit of rage over construction faults in a crucial power plant project at Huichon in Chagang Province.

The National Reunification Prize is an award of North Korea, bestowed by the Presidium of the Supreme People's Assembly upon people who have contributed to the reunification of Korea. The award was instituted in 1990.

Kim Yang-gon was a North Korean politician and a senior official of the ruling Workers' Party of Korea.

The United Front Department of the Workers' Party of Korea is a department of the Central Committee of the Workers' Party of Korea (WPK) tasked with relations with South Korea. It conducts propaganda operations and espionage and manages front organizations, including the Chongryon.

Hwang Sun-hui was a North Korean politician who served in several high-ranking positions in the Workers' Party of Korea (WPK), including in the Supreme People's Assembly and the Central Committee of the WPK. She was affiliated with the Korean Revolution Museum from 1965, and was its director from 1990.

The 8th Congress of the Workers' Party of Korea was held at the April 25 House of Culture in Pyongyang from 5 to 12 January 2021. A total of 7,000 people participated in the congress including 5,000 delegates. The Party Congress took place in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic where no cases were reported.

References

- ↑ Kim, Young Sik (2003-10-28). "The left-right confrontation in Korea – Its origin". Association for Asian Research. Archived from the original on 2007-02-27. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Russia Acknowledges Sending Japanese Prisoners of War to North Korea". Mosnews.com. 2005-04-01. Archived from the original on 2006-11-13. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ Morris-Suzuki, Tessa (2007-03-13). "The Forgotten Victims of the North Korean Crisis". Nautilus Institute. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ North Korea. Library of Congress Country Studies. 1994. Retrieved 2007-03-16. See section "Koreans Living Overseas".

- 1 2 Kim, Yong Mok (November 1997). "The Dilemma of North Korea's Japanese Wives". Japan Policy Research Institute Critique. 4 (10). Archived from the original on 2006-09-27. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ↑ Kang, Chol-hwan (2003-12-05). "Ethnic Koreans in Japan Victimized by the North Korean Regime's Fraud". The Chosun Ilbo . Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ↑ "Movements of the Japanese Red Army and the "Yodo-go" Group"" (PDF). National Police Agency, Japan. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-03-23. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Asian Political News (Kyodo) (2002-11-25). "N. Korean defector says 70-80 Japanese abducted by North". Asian Political News. Archived from the original on 2008-12-06. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- ↑ "North Korea rejects DNA link to Megumi Yokota abduction case". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2011-08-20. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- ↑ Green, Shane (2003-11-21). "Cult saga of sex, spies and defection". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2009-06-01.

- ↑ "Defector gives up on North Korea". BBC News. 2005-11-03. Retrieved 2009-06-01.