Related Research Articles

Wilma Pearl Mankiller was a Native American activist, social worker, community developer and the first woman elected to serve as Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation. Born in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, she lived on her family's allotment in Adair County, Oklahoma, until the age of 11, when her family relocated to San Francisco as part of a federal government program to urbanize Indigenous Americans. After high school, she married a well-to-do Ecuadorian and raised two daughters. Inspired by the social and political movements of the 1960s, Mankiller became involved in the Occupation of Alcatraz and later participated in the land and compensation struggles with the Pit River Tribe. For five years in the early 1970s, she was employed as a social worker, focusing mainly on children's issues.

Joan Hill, also known as Che-se-quah, was a Muscogee Creek artist of Cherokee ancestry. She was one of the most awarded Native American women artists in the 20th century.

Willard Stone was an American artist best known for his wood sculptures carved in a flowing Art Deco style.

The Bacone school or Bacone style of painting, drawing, and printmaking is a Native American intertribal "Flatstyle" art movement, primarily from the mid-20th century in Eastern Oklahoma and named for Bacone College. This art movement bridges historical, tribally-specific pictorial painting and carving practices towards an intertribal Modernist style of easel painting. This style is also influenced by the art programs of Chilocco Indian School, north of Ponca City, Oklahoma, and Haskell Indian Industrial Training Institute, in Lawrence, Kansas and features a mix of Southeastern, Prairie, and Central Plains tribes.

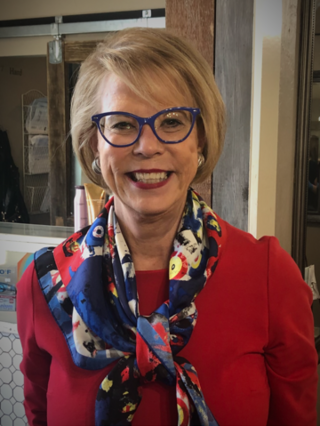

Terry Neese is an American businesswoman and politician. A member of the Republican Party, she was the first woman nominated by a major political party for the office of Lieutenant Governor of Oklahoma, in 1990; in 2020 she was a candidate for the Republican nomination in Oklahoma's 5th congressional district.

Susie Walking Bear Yellowtail (1903–1981) (Crow-Sioux) was the first Crow and one of the first Native Americans to graduate as a registered nurse in the United States. Working for the Indian Health Service, she brought modern health care to her people and traveled throughout the U.S. to assess care given to indigenous people for the Public Health Service. Yellowtail served on many national health organizations and received many honors for her work, including the President's Award for Outstanding Nursing Health Care in 1962 and being honored in 1978 as the "Grandmother of American Indian Nurses" by the American Indian Nurses Association. She was inducted into the Montana Hall of Fame in 1987 and in 2002 became the first Native American inductee of the American Nurses Association Hall of Fame.

Jennie Ross Cobb is the first known Native American woman photographer in the United States. She began taking pictures of her Cherokee community in the late 19th century. The Oklahoma Historical Society used her photos of the Murrell Home to restore that building, which is now a museum. Trained as a teacher, Cobb worked as a florist in Texas before returning to Oklahoma to spearhead the restoration of the Murrell Home.

Josephine Myers-Wapp was a Comanche weaver and educator. After completing her education at the Haskell Institute, she attended Santa Fe Indian School, studying weaving, dancing, and cultural arts. After her training, she taught arts and crafts at Chilocco Indian School before joining the faculty of the newly opened Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe. She taught weaving, design, and dance at the institute, and in 1968 was one of the coordinators for a dance exhibit at the Mexican Summer Olympic Games. In 1973, she retired from teaching to focus on her own work, exhibiting throughout the Americas and in Europe and the Middle East. She has work in the permanent collection of the IAIA and has been featured at the Smithsonian Institution. Between 2014 and 2016, she was featured in an exhibition of Native American women artists at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe.

Jeri Ah-be-hill was a Kiowa fashion expert and art dealer. She owned and operated a trading post on the Wind River Indian Reservation for more than twenty years before moving to Santa Fe, New Mexico where she became the curator of the annual Native American Clothing Contest held at the Santa Fe Indian Market. She also worked as a docent at both the Institute of American Indian Arts and the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian. Considered an expert on Native American fashion, she traveled nationally presenting educational information about tribal clothing.

Veronica Murdock is an American civil servant and of Shasta–Mohave ancestry, as a member of the Colorado River Indian Tribes. She served in the tribal administration, including as vice chair, of the Colorado River Tribe from 1969 to 1979 and between 1977 and 1979 as the first woman president of the National Congress of American Indians. From 1980 to 2004, she served as a civil service employee with the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Georgeann Robinson was an Osage teacher and businesswoman, who used her skill with ribbonwork to preserve the cultural heritage of her people. She was honored as a 1982 National Heritage Fellowship recipient by the National Endowment for the Arts and has works in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan, Museum of International Folk Art of Santa Fe, New Mexico and in the Southern Plains Indian Museum in Anadarko, Oklahoma. As an activist, from 1958, she was active in the National Congress of American Indians and in the late 1960s, was the executive vice president of the organization.

Southern Plains Indian Museum is a Native American museum located in Anadarko, Oklahoma. It was opened in 1948 under a cooperative governing effort by the United States Department of the Interior and the Oklahoma state government. The museum features cultural and artistic works from Oklahoma tribal peoples of the Southern Plains region, including the Caddo, Chiricahua Apache, Comanche, Delaware Nation, Kiowa, Plains Apache, Southern Arapaho, Southern Cheyenne, and Wichita.

Sandy Fife Wilson is a Muscogee (Creek) art educator, fashion designer and artist. After graduating from the Institute of American Indian Arts and Northeastern Oklahoma State University, she became an art teacher, first working in the public schools of Dewey, Oklahoma. When Josephine Wapp retired as the textile instructor at the Institute of American Indian Arts, Wilson was hired to teach the design courses. After three years, in 1979, she returned to Oklahoma and taught at Chilocco Indian School until it closed and then worked in the Morris Public School system until her retirement in 2009.

Jimmie Carole Fife Stewart is a Muscogee (Creek) art educator, fashion designer, and artist. After graduating from the Chilocco Indian School and taking courses at the University of Arizona, she earned a degree from Oklahoma State University and began working as a teacher. After a six-year stint working for Fine Arts Diversified, she returned to teaching in 1979 in Washington, Oklahoma. Primarily known as a painter, using watercolor or acrylic media, Fife-Stewart has also been involved in fashion design. Her works have been shown mostly in the southwestern United States and have toured South America. Having won numerous awards for her artworks, she was designated as a Master Artist by the Five Civilized Tribes Museum in 1997.

Valjean McCarty Hessing was a Choctaw painter, who worked in the Bacone flatstyle. Throughout her career, she won 9- awards for her work and was designated a Master Artist by the Five Civilized Tribes Museum in 1976. Her artworks are in collections of the Heard Museum of Phoenix, Arizona; the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma; the Southern Plains Indian Museum in Anadarko, Oklahoma; and the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian of Santa Fe, New Mexico, among others.

Mary Adair is a Cherokee Nation educator and painter based in Oklahoma.

Jane McCarty Mauldin was a Choctaw artist, who simultaneously worked in commercial and fine art exhibiting from 1963 through 1997. Over the course of her career, she won more than 100 awards for her works and was designated as a "Master Artist" by the Five Civilized Tribes Museum in Muskogee, Oklahoma. She has works in the permanent collections of the Heard Museum, the Heritage Center of the Red Cloud Indian School and the collections of the Department of the Interior, as well as various private collections.

Alice Littleman was a Kiowa beadwork artist and regalia maker, who during her lifetime was recognized as one of the leading Kiowa beaders and buckskin dressmakers. Her works are included in the permanent collections of the National Museum of Natural History, the National Museum of the American Indian, the Southern Plains Indian Museum, and the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Joan Brown is an American artist, illustrator and educator. She is of Cherokee and Creek descent from Oklahoma. Her work is of the Bacone school style.

Atalie Unkalunt was a Cherokee singer, interior designer, activist, and writer. Her English name Iva J. Rider appears on the final rolls of the Cherokee Nation. Born in Indian Territory, she attended government-run Indian schools and then graduated from high school in Muskogee, Oklahoma. She furthered her education at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, Massachusetts. After a thirteen-month engagement with the YMCA as a stenographer and entertainer for World War I troops in France, she returned to the United States in 1919 and continued her music studies. By 1921, she was living in New York City and performing a mixture of operatic arias, contemporary songs, and Native music. Her attempts to become an opera performer were not successful. She was more accepted as a so-called "Indian princess", primarily singing the works of white composers involved in the Indianist movement.

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 Broder 2013, p. 268.

- 1 2 The McIntosh County Democrat 1971, p. 5.

- ↑ U. S. Census 1940, p. 12A.

- ↑ Brus 1991, p. 63.

- 1 2 3 Kilpatrick 1992, p. 46.

- ↑ The McIntosh County Democrat 1977, p. 2.

- ↑ Love 1990, p. 75.

- 1 2 Love 1990, p. 76.

- 1 2 3 Blackwell 2000, p. 12B.

- 1 2 3 Woodruff 2015.

- 1 2 3 Warlick 2015, p. 3A.

- 1 2 Power 2007, p. 195.

- 1 2 Anderson 1988, p. 66.

- 1 2 The Santa Fe New Mexican 1990, p. 5.

- 1 2 Tilove 1993, p. 25.

- 1 2 Tilove 1993, p. 26.

- ↑ Kamins 1992, p. 114.

- ↑ Churchill 2003, p. 243.

- ↑ The Daily Oklahoman 1991, p. 16.

- ↑ Hapiuk 2001, p. 1035.

- ↑ Osborne 2003, pp. 221–222.

- ↑ Hapiuk 2001, pp. 1036–1037.

- ↑ The Hartford Courant 1995, p. 84.

- ↑ Schulte 1996, pp. 49–50.

- 1 2 Sanchez 2007, p. F1.

- ↑ The Atlanta Journal-Constitution 2000, p. J7.

- 1 2 Smoot 2019.

- ↑ McKie 2011.

- ↑ Cherokee Nation Government Relations 2009, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Edmon Low Library 2012.

- ↑ "Fontenot v. Hunter, Attorney General of Oklahoma".

- ↑ "Oklahoma officials agree to stay enforcement of unconstitutional American Indian art law". 5 January 2017.

- ↑ Smoot 2017.

- 1 2 "UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF OKLAHOMA: Fontenot v. Hunter. Court Opinion. Case No. CIV-16-1339-G" (PDF). pacificlegal.org.

- ↑ Spaulding 2019.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Nina L. (August 10, 1988). "'Cherokee Legends' Opens at Museum". Asheville Citizen-Times . Asheville, North Carolina. p. 66. Retrieved 7 August 2019– via Newspapers.com.

- Blackwell, S. (October 6, 2000). "Playing Politics with Native American art". The Southeast Missourian . Cape Girardeau, Missouri. p. 12B. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- Broder, Patricia Janis (2013). Earth Songs, Moon Dreams: Paintings by American Indian Women. New York, New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1-4668-5972-2.

- Brus, Brian (June 5, 1991). "Festival to Show Non-registered Indians' Work". The Oklahoman . Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Associated Press. p. 63. Retrieved 7 August 2019– via Newspapers.com.

- Cherokee Nation Government Relations (2009). Support the Federal Recognition ProcessTo Protect All Tribal Citizens (PDF). Tahlequah, Oklahoma: Cherokee Nation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 September 2013.

- Churchill, Ward (2003). Perversions of Justice: Indigenous Peoples and Anglo-american Law. San Francisco, California: City Lights Bookstore. ISBN 978-0-87286-411-5.

- Hapiuk, William J. Jr. (April 2001). "Of Kitsch and Kachinas: A Critical Analysis of the 'Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990'". Stanford Law Review . 53 (4). Stanford, California: Stanford Law School: 1009–1075. doi:10.2307/1229497. ISSN 0038-9765. JSTOR 1229497.

- Kamins, Charles (September 1992). "Addendum: Ethnic Cleansing? We Have It Here, Too!". International Journal on World Peace. 9 (3). St. Paul, Minnesota: Paragon House: 111–115. ISSN 0742-3640. JSTOR 20751827.

- Kilpatrick, James J. (December 13, 1992). "Indian Artists Form Tight Closed Shop". The Montgomery Advertiser . Montgomery, Alabama. p. 46. Retrieved 7 August 2019– via Newspapers.com.

- Love, Bernice (February 18, 1990). "Cherokee Women Come Alive on Canvas (pt. 1)". The Oklahoman . Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. p. 75. Retrieved 8 August 2019– via Newspapers.com. and Love, Bernice (February 18, 1990). "Artist (pt. 2)". The Oklahoman . Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. p. 76. Retrieved 8 August 2019– via Newspapers.com.

- McKie, Scott (October 14, 2011). "Tribe establishes Cherokee Identity Protection Committee". Cherokee One Feather. Cherokee, North Carolina. Archived from the original on May 29, 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- Osborne, Stephen D. (2003). "Addendum: Protecting Tribal Stories: The Perils of Propertization". American Indian Law Review . 28 (1). Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma College of Law: 203–236. doi:10.2307/20171720. ISSN 0094-002X. JSTOR 20171720.

- Power, Susan C. (2007). Art of the Cherokee: Prehistory to the Present. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-2766-2.

- Sanchez, Aurelio (March 4, 2007). "Crafts fest like home for noted illustrator (pt. 1)". The Albuquerque Journal . Albuquerque, New Mexico. p. F1. Retrieved 8 August 2019– via Newspapers.com. and Sanchez, Aurelio (March 4, 2007). "Crafts fest like home for noted illustrator (pt. 2)". The Albuquerque Journal . Albuquerque, New Mexico. p. F2. Retrieved 8 August 2019– via Newspapers.com.

- Schulte, Eileen M. (December 28, 1996). "Paintings depict a shared suffering (pt. 1)". The Tampa Tribune . Tampa, Florida. p. 49. Retrieved 8 August 2019– via Newspapers.com. and Schulte, Eileen M. (December 28, 1996). "Sisters/Series of paintings celebrates black, Indian women (pt. 2)". The Tampa Tribune . Tampa, Florida. p. 50. Retrieved 8 August 2019– via Newspapers.com.

- Smoot, D. E. (October 29, 2017). "Artists to return to show while status of law pending". Muskogee Phoenix . Muskogee, Oklahoma. Archived from the original on August 7, 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- Smoot, D. E. (May 8, 2019). "Judge rejects state's effort to restrict Native art". The Tahlequah Daily Press . Tahlequah, Oklahoma. Archived from the original on August 5, 2019. Retrieved August 5, 2019.

- Spaulding, Cathy (May 8, 2019). "Women the focus of art exhibit". The Muskogee Phoenix . Muskogee, Oklahoma. Archived from the original on August 3, 2019. Retrieved August 4, 2019.

- Tilove, Jonathan (May 16, 1993). "Who is an Indian? (pt. 1)". The Santa Fe New Mexican . Santa Fe, New Mexico. Newhouse News Service. p. 25. Retrieved 7 August 2019– via Newspaperarchive.com. and Tilove, Jonathan (May 16, 1993). "Indian? (pt. 2)". The Santa Fe New Mexican . Santa Fe, New Mexico. Newhouse News Service. p. 26. Retrieved 7 August 2019– via Newspaperarchive.com.

- Warlick, Heather (November 8, 2015). "Native American Heritage Month: Keeping the Culture Alive (pt. 1)". The Oklahoman . Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. p. 1A. Retrieved 8 August 2019– via Newspapers.com., Warlick, Heather (November 8, 2015). "Culture: 'We really want our children to know the history' (pt. 2 )". The Oklahoman . Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. p. 2A. Retrieved 8 August 2019– via Newspapers.com., and Warlick, Heather (November 8, 2015). "Culture: 'Relationship with the land' (pt. 3 )". The Oklahoman . Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. p. 3A. Retrieved 8 August 2019– via Newspapers.com.

- Woodruff, Kimberly (November 25, 2015). "Luncheon celebrates Native American culture". tinker.af.mil. Del City, Oklahoma: Tinker Air Force Base. Archived from the original on 7 August 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- "1940 U. S. Census: Darling Township, Muskogee county, Oklahoma". FamilySearch. Washington, D. C.: National Archives and Records Administration. 24 April 1940. p. 12A. NARA digital publication T627, Roll #3313, lines 2–5. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- "Atlanta Spirit of America". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution . Atlanta, Georgia. March 3, 2000. p. J-7.

- "Drive to Restore Old Oktaha School Building". The McIntosh County Democrat. Checotah, Oklahoma. September 1, 1977. p. 2. Retrieved 7 August 2019– via Newspaperarchive.com.

- "Feds probe peddling of fake Indian Art". The Santa Fe New Mexican . Santa Fe, New Mexico. Associated Press. September 8, 1990. p. 5. Retrieved 7 August 2019– via Newspaperarchive.com.

- "Institute for American Indian Studies". The Hartford Courant . Hartford, Connecticut. September 28, 1995. p. 84. Retrieved 8 August 2019– via Newspapers.com.

- "Jeanne Rorex Bridges". ListenOK, Oklahoma Native Artist Oral History Project. Stillwater, Oklahoma: Edmon Low Library. May 17, 2012. Archived from the original on 7 August 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- "Mankiller Says Tribe Can't Certify Artists as Cherokee Tribal Members". The Oklahoman . Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Associated Press. February 20, 1991. p. 16. Retrieved 7 August 2019– via Newspaperarchive.com.

- "Miss Jean Walker Wedded to Kenneth Rorex, Friday". The McIntosh County Democrat. Checotah, Oklahoma. March 25, 1971. p. 5. Retrieved 7 August 2019– via Newspaperarchive.com.