Afula is a city in the Northern District of Israel, often known as the "Capital of the Valley" due to its strategic location in the Jezreel Valley. As of 2022, the city had a population of 61,519.

Ma'alul was a Palestinian village, with a mixed population of primarily Muslims with a substantial minority of Palestinian Christians, that was depopulated and destroyed by Israel during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. Located six kilometers west of the city of Nazareth, many of its inhabitants became internally displaced refugees, after taking refuge in Nazareth and the neighbouring town of Yafa an-Naseriyye. Despite having never left the territory that came to form part of Israel, the majority of the villagers of Maalul, and other Palestinian villages like Andor and Al-Mujidal, were declared "absentees", allowing the confiscation of their land under the Absentees Property Law.

The Jezreel Valley, or Marj Ibn Amir, also known as the Valley of Megiddo, is a large fertile plain and inland valley in the Northern District of Israel. It is bordered to the north by the highlands of the Lower Galilee region, to the south by the Samarian highlands, to the west and northwest by the Mount Carmel range, and to the east by the Jordan Valley, with Mount Gilboa marking its southern extent. The largest settlement in the valley is the city of Afula, which lies near its center.

Tulkarm or Tulkarem is a Palestinian city in the West Bank, the capital of the Tulkarm Governorate of the State of Palestine. The Israeli city of Netanya is to the west, and the Palestinian cities of Nablus and Jenin to the east. According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, in 2017 Tulkarm had a population of 64,532. Tulkarm is under the administration of the Palestinian National Authority.

Yehoshua Hankin was a Zionist activist who was responsible for most of the major land purchases of the Zionist Organization in Ottoman Palestine and Mandatory Palestine – in particular for the Sursock Purchase.

Nahalal is a moshav in northern Israel. Covering 8.5 square kilometers (3.3 sq mi), it falls under the jurisdiction of the Jezreel Valley Regional Council. In 2022 it had a population of 1,351.

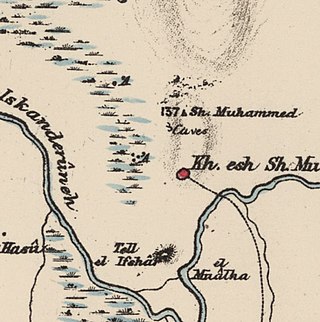

Zir'in was a Palestinian Arab village of over 1,400 in the Jezreel Valley, located 11 kilometers (6.8 mi) north of Jenin. Identified as the ancient town of Yizre'el (Jezreel), it was known as Zir'in during Islamic rule, and was near the site of the Battle of Ain Jalut, in which the Mamluks halted Mongol expansion southward. Under the Ottomans, it was a small village, expanding during the British Mandate in the early 20th century. After its capture by Israel in 1948, Zir'in was destroyed. The Israeli kibbutz of Yizre'el was established shortly after on the village lands of Zir'in.

Gesher is a kibbutz in the Beit She'an Valley in northeastern Israel. Founded in 1939 by Jewish refugees from Germany, it falls under the jurisdiction of Valley of Springs Regional Council. It is situated 10 km south of kibbutz Deganya Aleph and 15 km south of Tiberias. The population is approximately 500 inhabitants.

Huj was a Palestinian Arab village located 15 kilometers (9.3 mi) northeast of Gaza City. Identified as the site of the ancient Philistine town of Oga, the modern village was founded by the Ottomans in the early 19th century.

Land and property laws in Israel are the property law component of Israeli law, providing the legal framework for the ownership and other in rem rights towards all forms of property in Israel, including real estate (land) and movable property. Besides tangible property, economic rights are also usually treated as property, in addition to being covered by the law of obligations.

The Palestinian people are an ethnonational group with family origins in the region of Palestine. Since 1964, they have been referred to as Palestinians, but before that they were usually referred to as Palestinian Arabs. During the period of the British Mandate, the term Palestinian was also used to describe the Jewish community living in Palestine.

Jalqamus is a Palestinian village in the West Bank, located 10 km southeast of the city of Jenin in the northern West Bank. According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, the town had a population of 1,867 inhabitants in mid-year 2006 and 2,624 by 2017.

Alonim is a kibbutz in northern Israel. Located in the Lower Galilee, it falls under the jurisdiction of Jezreel Valley Regional Council. In 2022 the kibbutz had a population of 552.

Naghnaghiya was a Palestinian Arab village, 28.5 kilometers (17.7 mi) southeast of Haifa. It was depopulated before the outbreak of the 1948 Arab-Israeli war.

Daliyat al-Rawha' was a Palestinian village located 24.5 kilometers (15.2 mi) southeast of Haifa. It was the site of the signing of a ceasefire agreement between the forces of the Mamluks and the Crusaders in the 13th century. A small village of 60 Arab Muslims in the late 19th century, the kibbutz of Dalia was established on land purchased in the village in 1939. The population in 1945 reached 600 people: 280 Arabs and 320 Jews. It was depopulated of its Arab inhabitants in late March during the 1947–1948 civil war in Mandatory Palestine.

Zarnuqa, also Zarnuga, was a Palestinian Arab village in the Ramle Subdistrict. It was depopulated on 27–28 May 1948 during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War.

Wadi al-Hawarith was a Palestinian bedouin camping site in the Tulkarm Subdistrict. It was depopulated at the outbreak of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War on March 15, 1948, following the 1947–48 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine. It was located 16.5 km northwest of Tulkarm. Wadi al-Hawarith was mostly destroyed with the exception of four houses.

Nuris was a Palestinian Arab village in the District of Jenin. In 1945, Nuris had 570 inhabitants. It was depopulated during the 1948 War on 29 May 1948 under Operation Gideon. The Israeli moshav of Nurit was built on Nuris' village land in 1950.

Mandatory Palestine was a geopolitical entity that existed between 1920 and 1948 in the region of Palestine under the terms of the League of Nations Mandate for Palestine.

The Sursock Purchases were land purchases made by Jewish organizations from the Greek Sursock family, mainly from 1901 to 1925. These included the Jezreel Valley and Haifa Bay, as well as other lands in what became the Mandate for Palestine. These collectively formed the largest Jewish land purchase in Palestine during the period of early Jewish immigration.