The National Woman's Party (NWP) was an American women's political organization formed in 1916 to fight for women's suffrage. After achieving this goal with the 1920 adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, the NWP advocated for other issues including the Equal Rights Amendment. The most prominent leader of the National Woman's Party was Alice Paul, and its most notable event was the 1917–1919 Silent Sentinels vigil outside the gates of the White House.

Josephine Sophia White Griffing was an American reformer who campaigned against slavery and for women's rights. In Litchfield, Ohio, their home was a stop on the Underground Railroad and she worked as a lecturer for the Western Anti-Slavery Society and Ohio Women's Rights Association. At the end of the American Civil War she moved to Washington, D.C., to help work with the unemployed freedmen. Much of her work was done through the Freedmen's Bureau, where she worked as an assistant to the assistant commissioner and as an agent. Griffing was also active in several women's rights organizations, including the National Woman Suffrage Association.

Isabella Beecher Hooker was a leader, lecturer and social activist in the American suffragist movement.

Katharine Martha Houghton Hepburn was an American feminist social reformer and a leader of the suffrage movement in the United States. Hepburn served as president of the Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association before joining the National Woman's Party. In 1923 Hepburn formed the Connecticut Branch of the American Birth Control League with two of her friends, Mrs. George Day and Mrs. M. Toscan Bennett. She was the mother and namesake of actress Katharine Hepburn and the grandmother and namesake of actress Katharine Houghton.

Women's suffrage was established in the United States on a full or partial basis by various towns, counties, states, and territories during the latter decades of the 19th century and early part of the 20th century. As women received the right to vote in some places, they began running for public office and gaining positions as school board members, county clerks, state legislators, judges, and, in the case of Jeannette Rankin, as a member of Congress.

Josephine Marshall Jewell Dodge was an American educator, social reformer, and prominent anti-suffragist. She was the daughter of Marshall Jewell, who served as Governor of Connecticut and United States Postmaster General.

Mary Garrett Hay was an American suffragist and community organizer. She served as president of the Women's City Club of New York, the Woman Suffrage Party and the New York Equal Suffrage League. Hay was known for creating woman's suffrage groups across the country. She was also close to the notable suffragist, Carrie Chapman Catt, with one contemporary, Rachel Foster Avery, stating that Hay "really loves" Catt.

The Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association (CWSA) was founded on October 28, 1869, by Isabella Beecher Hooker and Frances Ellen Burr at Connecticut's first suffrage convention. Its main goal was to persuade the Connecticut General Assembly to ratify the 19th amendment, giving women in Connecticut the right to vote. Throughout its 52 years of existence, the CWSA helped to pass local legislation and participated in the national fight for women's suffrage. It cooperated with the National Women's Suffrage Association through national protests and demonstrations. As well as advocating for women's suffrage, this association was active in promoting labor regulations, debating social issues, and fighting political corruption.

The Massachusetts Association Opposed to the Further Extension of Suffrage to Women (MAOFESW) was one of the earliest organizations formed to oppose women's suffrage in the United States. The organization was founded in May of 1895. However, MAOFESW had its roots in earlier Massachusetts anti-suffrage groups and had a publication called The Remonstrance, started in 1890.

Lillian Ascough was an American suffragist. Originally from Detroit, Michigan, she served as the Connecticut chair of the National Woman's Party (NWP) and as the vice president of the Michigan branch of the NWP. At the August 1918 demonstration at Lafayette Square, Ascough was sentenced to fifteen days in jail. Then, in February 1919 she participated in the watchfire demonstrations and was again arrested and sentenced to five days in jail. She was a speaker in the Prison Special tour of the U.S. during February and March 1919.

The "Prison Special" was a train tour organized by suffragists who, as members of the Silent Sentinels and other demonstrations, had been jailed for picketing the White House in support of passage of the federal women's suffrage amendment. In February 1919, 26 members of the National Woman's Party boarded a chartered train they dubbed the "Democracy Limited" in Washington, D.C. They visited cities across the country where they spoke to large crowds about their experiences as political prisoners at Occoquan Workhouse, and were typically dressed in their prison uniforms. The tour, which concluded in March 1919, helped create support for the ratification effort that ended with the adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment on August 26, 1920.

Amelia "Mimi" Himes Walker was an American suffragist and women's rights activist. Walker was one of the Silent Sentinels who picketed outside of the White House for women's right to vote. She was arrested in 1917 and sentenced to 60 days in the workhouse. After women secured the right to vote, Walker continued to honor the efforts of the suffragists. She also promoted the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA).

Ella Riegel was an American suffragist and women's rights activist. Riegel was a graduate of the first class of Bryn Mawr College and would remain associated with the college the rest of her life.

Katharine Ludington was an American suffragist. She was the last president of the Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association, and a founding leader of the League of Women Voters.

Catherine Mary Flanagan was an American suffragist affiliated with the Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association and later the National Woman's Party. She was among the Silent Sentinels arrested for protesting outside the White House in 1917.

Frances Ellen Burr was an American suffragist and writer from Connecticut.

Emily Pierson was an American suffragist and physician. Early in her career, Pierson worked as a teacher, and then later, as an organizer for the Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association (CWSA). After women earned the right to vote, she went back to school to become a physician in her hometown of Cromwell, Connecticut. During much of her life, she was interested in socialism, studying and observing in both Russia and China.

Elizabeth Daken Bacon was an American suffragist and educator. She served as president of the Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association (CWSA) from 1906 to 1910.

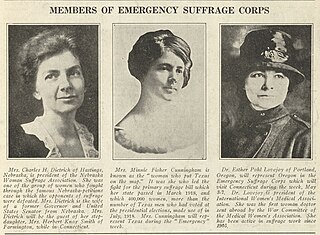

The Suffrage Emergency Corps was a special group of suffragists formed after nearly two-thirds of the states had ratified the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Only one more state was needed to ratify, and suffragists hoped they could convince Governor Marcus H. Holcomb to make his state of Connecticut the thirty-sixth. A team of women, sponsored by the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) chose delegates from the other states to travel to Connecticut in early May 1920 to convince the governor to open a special legislative session to consider ratifying the amendment. The event garnered publicity, but it did not convince the governor to proceed with the session.