Lake Michigan is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is the second-largest of the Great Lakes by volume and the third-largest by surface area, after Lake Superior and Lake Huron. To the east, its basin is conjoined with that of Lake Huron through the 3+1⁄2 miles wide, 295 feet deep, Straits of Mackinac, giving it the same surface elevation as its easterly counterpart; the two are technically a single lake.

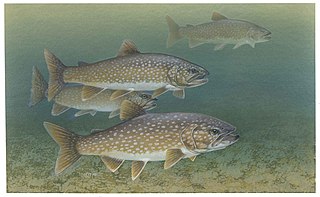

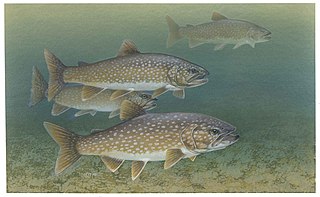

The lake trout is a freshwater char living mainly in lakes in northern North America. Other names for it include mackinaw, namaycush,lake char (or charr), touladi, togue, and grey trout. In Lake Superior, it can also be variously known as siscowet, paperbelly and lean. The lake trout is prized both as a game fish and as a food fish. Those caught with dark coloration may be called mud hens.

Manistique is the only city and county seat of Schoolcraft County in the U.S. state of Michigan. As of the 2020 census, the city population was 2,828.

Lake of the Woods is a lake occupying parts of the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Manitoba and the U.S. state of Minnesota. Lake of the Woods is over 70 miles (110 km) long and wide, containing more than 14,552 islands and 65,000 miles (105,000 km) of shoreline. It is fed by the Rainy River, Shoal Lake, Kakagi Lake and other smaller rivers. The lake drains into the Winnipeg River and then into Lake Winnipeg. Ultimately, its outflow goes north through the Nelson River to Hudson Bay.

Ahjumawi Lava Springs State Park is a state park of California in the United States. It is located in remote northeastern Shasta County and is only accessible to the public by boat.

The Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness is a 1,090,000-acre (4,400 km2) wilderness area within the Superior National Forest in the northeastern part of the US state of Minnesota under the administration of the U.S. Forest Service. A mixture of forests, glacial lakes, and streams, the BWCAW's preservation as a primitive wilderness began in the 1900s and culminated in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness Act of 1978. It is a popular destination for canoeing, hiking, and fishing, and is one of the most visited wildernesses in the United States.

Henry Rowe Schoolcraft was an American geographer, geologist, and ethnologist, noted for his early studies of Native American cultures, as well as for his 1832 expedition to the source of the Mississippi River. He is also noted for his major six-volume study of Native Americans commissioned by Congress and published in the 1850s.

The Spanish River is a river in Algoma District, Sudbury District and Greater Sudbury in Northeastern Ontario, Canada. It flows 338 kilometres (210 mi) in a southerly direction from its headwaters at Spanish Lake and Duke Lake to its mouth at the North Channel of Lake Huron just outside the community of Spanish.

The Watauga River is a large stream of western North Carolina and East Tennessee. It is 78.5 miles (126.3 km) long with its headwaters in Linville Gap to the South Fork Holston River at Boone Lake.

The Yellow Dog River flows through Marquette County in the Upper Peninsula of the U.S. state of Michigan. It is 31.6 miles (50.9 km) in length, with about 85 miles (137 km) of tributaries. The main branch begins at the outflow from Bulldog Lake in the Ottawa National Forest on the boundary between Baraga and Marquette counties. The river's mouth is on Lake Independence, near Big Bay, Michigan, and is part of the Lake Superior watershed.

The Tahquamenon River is an 89.1-mile-long (143.4 km) blackwater river in the U.S. state of Michigan that flows in a generally eastward direction through the eastern end of the Upper Peninsula. It drains approximately 820 square miles (2,120 km2) of the Upper Peninsula, including large sections of Luce County and Chippewa County. It begins in the Tahquamenon Lakes in northeast Columbus Township of Luce County and empties into Lake Superior near the village of Paradise. M-123 runs alongside a portion of the river.

Palms Book State Park is a publicly owned nature preserve encompassing 388 acres (157 ha) in Thompson Township, Schoolcraft County, in the eastern Upper Peninsula of Michigan. The state park is noted for Kitch-iti-kipi, the "Big Spring" of the Upper Peninsula.

The Manistee River, seldom referred to as the Big Manistee River, runs 190 miles (310 km) through the northwestern Lower Peninsula of Michigan; it now passes through the contemporary villages of Sharon, Smithville, and Mesick, entering Lake Michigan at Manistee. It is considered, like the nearby Au Sable River, to be one of the best trout fisheries east of the Rockies. The Manistee River is also being considered for restoration of Arctic grayling, which have been extirpated from the State of Michigan since 1936.

Torch Lake is a lake in the Northern Lower Peninsula of the U.S. state of Michigan. At 19 miles (31 km) long, is Michigan's longest inland lake, and at approximately 29.3 mi2 (76 km2), it is Michigan's second largest inland lake, after Houghton Lake. It has a maximum depth of 310 feet (94 m) and an average depth of 111 feet (34 m), making it Michigan's deepest inland lake, as well as the state's largest by volume.

M-149 is a 10.6-mile (17.1 km) north–south state trunkline highway in the Upper Peninsula of the US state of Michigan. It connects US Highway 2 (US 2) in Thompson with the Palms Book and Indian Lake state parks. The highway was originally designed in the 1930s and extended a few years later. The last major changes to the highway were made in the 1960s when it was completely paved for the first time.

Maiden Creek is a 20.3-mile-long (32.7 km) tributary of the Schuylkill River in Berks County, Pennsylvania. The name "Maiden" is an English translation of the Native American word Ontelaunee. Maiden Creek is formed by the confluence of Ontelaunee and Kistler creeks in the community of Kempton. The tributary Sacony Creek joins at the community of Virginville.

Lackawanna State Park is a 1,445-acre (585 ha) Pennsylvania state park in Benton and North Abington Townships, Lackawanna County, Pennsylvania in the United States. Lake Lackawanna, a 198-acre (80 ha) man-made lake, is the central focus of recreation at the park. Lackawanna State Park is located near Dalton on Pennsylvania Route 524 just off exit 199 of Interstate 81.

There are three Manistique Lakes in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. The lakes include North Manistique Lake, Big Manistique Lake, and South Manistique Lake. The towns surrounding the lakes are Curtis, Germfask, and Helmer. The lakes are known for vacationing and fishing. They are also in close proximity to other natural sights such as the Great Lakes, rivers, and smaller lakes as well as tourist attractions including the Canada–US border, the Soo Locks, Mackinac Island, parks, and museums.