In physics, physical chemistry and engineering, fluid dynamics is a subdiscipline of fluid mechanics that describes the flow of fluids — liquids and gases. It has several subdisciplines, including aerodynamics and hydrodynamics. Fluid dynamics has a wide range of applications, including calculating forces and moments on aircraft, determining the mass flow rate of petroleum through pipelines, predicting weather patterns, understanding nebulae in interstellar space and modelling fission weapon detonation.

In fluid dynamics, turbulence or turbulent flow is fluid motion characterized by chaotic changes in pressure and flow velocity. It is in contrast to laminar flow, which occurs when a fluid flows in parallel layers with no disruption between those layers.

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) is a branch of fluid mechanics that uses numerical analysis and data structures to analyze and solve problems that involve fluid flows. Computers are used to perform the calculations required to simulate the free-stream flow of the fluid, and the interaction of the fluid with surfaces defined by boundary conditions. With high-speed supercomputers, better solutions can be achieved, and are often required to solve the largest and most complex problems. Ongoing research yields software that improves the accuracy and speed of complex simulation scenarios such as transonic or turbulent flows. Initial validation of such software is typically performed using experimental apparatus such as wind tunnels. In addition, previously performed analytical or empirical analysis of a particular problem can be used for comparison. A final validation is often performed using full-scale testing, such as flight tests.

The Knudsen number (Kn) is a dimensionless number defined as the ratio of the molecular mean free path length to a representative physical length scale. This length scale could be, for example, the radius of a body in a fluid. The number is named after Danish physicist Martin Knudsen (1871–1949).

In fluid dynamics, d'Alembert's paradox is a paradox discovered in 1752 by French mathematician Jean le Rond d'Alembert. d'Alembert proved that – for incompressible and inviscid potential flow – the drag force is zero on a body moving with constant velocity relative to the fluid. Zero drag is in direct contradiction to the observation of substantial drag on bodies moving relative to fluids, such as air and water; especially at high velocities corresponding with high Reynolds numbers. It is a particular example of the reversibility paradox.

Darcy's law is an equation that describes the flow of a fluid through a porous medium. The law was formulated by Henry Darcy based on results of experiments on the flow of water through beds of sand, forming the basis of hydrogeology, a branch of earth sciences. It is analogous to Ohm's law in electrostatics, linearly relating the volume flow rate of the fluid to the hydraulic head difference via the hydraulic conductivity. In fact, the Darcy's law is a special case of the Stokes equation for the momentum flux, in turn deriving from the momentum Navier-Stokes equation.

Stokes flow, also named creeping flow or creeping motion, is a type of fluid flow where advective inertial forces are small compared with viscous forces. The Reynolds number is low, i.e. . This is a typical situation in flows where the fluid velocities are very slow, the viscosities are very large, or the length-scales of the flow are very small. Creeping flow was first studied to understand lubrication. In nature, this type of flow occurs in the swimming of microorganisms and sperm. In technology, it occurs in paint, MEMS devices, and in the flow of viscous polymers generally.

Fluid mechanics is the branch of physics concerned with the mechanics of fluids and the forces on them. It has applications in a wide range of disciplines, including mechanical, aerospace, civil, chemical, and biomedical engineering, as well as geophysics, oceanography, meteorology, astrophysics, and biology.

In fluid dynamics, inviscid flow is the flow of an inviscid fluid which is a fluid with zero viscosity.

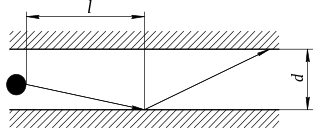

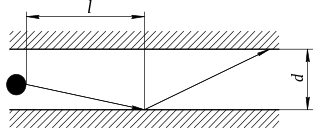

Knudsen diffusion, named after Martin Knudsen, is a means of diffusion that occurs when the scale length of a system is comparable to or smaller than the mean free path of the particles involved. An example of this is in a long pore with a narrow diameter (2–50 nm) because molecules frequently collide with the pore wall. As another example, consider the diffusion of gas molecules through very small capillary pores. If the pore diameter is smaller than the mean free path of the diffusing gas molecules, and the density of the gas is low, the gas molecules collide with the pore walls more frequently than with each other, leading to Knudsen diffusion.

Free molecular flow describes the fluid dynamics of gas where the mean free path of the molecules is larger than the size of the chamber or of the object under test. For tubes/objects of the size of several cm, this means pressures well below 10−3 mbar. This is also called the regime of high vacuum, or even ultra-high vacuum. This is opposed to viscous flow encountered at higher pressures. The presence of free molecular flow can be calculated, at least in estimation, with the Knudsen number (Kn). If Kn > 10, the system is in free molecular flow, also known as Knudsen flow. Knudsen flow has been defined as the transitional range between viscous flow and molecular flow, which is significant in the medium vacuum range where λ ≈ d.

In nonideal fluid dynamics, the Hagen–Poiseuille equation, also known as the Hagen–Poiseuille law, Poiseuille law or Poiseuille equation, is a physical law that gives the pressure drop in an incompressible and Newtonian fluid in laminar flow flowing through a long cylindrical pipe of constant cross section. It can be successfully applied to air flow in lung alveoli, or the flow through a drinking straw or through a hypodermic needle. It was experimentally derived independently by Jean Léonard Marie Poiseuille in 1838 and Gotthilf Heinrich Ludwig Hagen, and published by Hagen in 1839 and then by Poiseuille in 1840–41 and 1846. The theoretical justification of the Poiseuille law was given by George Stokes in 1845.

In fluid dynamics, hydrodynamic stability is the field which analyses the stability and the onset of instability of fluid flows. The study of hydrodynamic stability aims to find out if a given flow is stable or unstable, and if so, how these instabilities will cause the development of turbulence. The foundations of hydrodynamic stability, both theoretical and experimental, were laid most notably by Helmholtz, Kelvin, Rayleigh and Reynolds during the nineteenth century. These foundations have given many useful tools to study hydrodynamic stability. These include Reynolds number, the Euler equations, and the Navier–Stokes equations. When studying flow stability it is useful to understand more simplistic systems, e.g. incompressible and inviscid fluids which can then be developed further onto more complex flows. Since the 1980s, more computational methods are being used to model and analyse the more complex flows.

In fluid dynamics, the Reynolds number is a dimensionless quantity that helps predict fluid flow patterns in different situations by measuring the ratio between inertial and viscous forces. At low Reynolds numbers, flows tend to be dominated by laminar (sheet-like) flow, while at high Reynolds numbers, flows tend to be turbulent. The turbulence results from differences in the fluid's speed and direction, which may sometimes intersect or even move counter to the overall direction of the flow. These eddy currents begin to churn the flow, using up energy in the process, which for liquids increases the chances of cavitation.

Particle-laden flows refers to a class of two-phase fluid flow, in which one of the phases is continuously connected and the other phase is made up of small, immiscible, and typically dilute particles. Fine aerosol particles in air is an example of a particle-laden flow; the aerosols are the dispersed phase, and the air is the carrier phase.

In fluid mechanics, non-dimensionalization of the Navier–Stokes equations is the conversion of the Navier–Stokes equation to a nondimensional form. This technique can ease the analysis of the problem at hand, and reduce the number of free parameters. Small or large sizes of certain dimensionless parameters indicate the importance of certain terms in the equations for the studied flow. This may provide possibilities to neglect terms in the considered flow. Further, non-dimensionalized Navier–Stokes equations can be beneficial if one is posed with similar physical situations – that is problems where the only changes are those of the basic dimensions of the system.

Fluid motion is governed by the Navier–Stokes equations, a set of coupled and nonlinear partial differential equations derived from the basic laws of conservation of mass, momentum and energy. The unknowns are usually the flow velocity, the pressure and density and temperature. The analytical solution of this equation is impossible hence scientists resort to laboratory experiments in such situations. The answers delivered are, however, usually qualitatively different since dynamical and geometric similitude are difficult to enforce simultaneously between the lab experiment and the prototype. Furthermore, the design and construction of these experiments can be difficult, particularly for stratified rotating flows. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) is an additional tool in the arsenal of scientists. In its early days CFD was often controversial, as it involved additional approximation to the governing equations and raised additional (legitimate) issues. Nowadays CFD is an established discipline alongside theoretical and experimental methods. This position is in large part due to the exponential growth of computer power which has allowed us to tackle ever larger and more complex problems.

The contemporary conjugate convective heat transfer model was developed after computers came into wide use in order to substitute the empirical relation of proportionality of heat flux to temperature difference with heat transfer coefficient which was the only tool in theoretical heat convection since the times of Newton. This model, based on a strictly mathematically stated problem, describes the heat transfer between a body and a fluid flowing over or inside it as a result of the interaction of two objects. The physical processes and solutions of the governing equations are considered separately for each object in two subdomains. Matching conditions for these solutions at the interface provide the distributions of temperature and heat flux along the body–flow interface, eliminating the need for a heat transfer coefficient. Moreover, it may be calculated using these data.

Quadrature-based moment methods (QBMM) are a class of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) methods for solving Kinetic theory and is optimal for simulating phases such as rarefied gases or dispersed phases of a multiphase flow. The smallest "particle" entities which are tracked may be molecules of a single phase or granular "particles" such as aerosols, droplets, bubbles, precipitates, powders, dust, soot, etc. Moments of the Boltzmann equation are solved to predict the phase behavior as a continuous (Eulerian) medium, and is applicable for arbitrary Knudsen number and arbitrary Stokes number . Source terms for collision models such as Bhatnagar-Gross-Krook (BGK) and models for evaporation, coalescence, breakage, and aggregation are also available. By retaining a quadrature approximation of a probability density function (PDF), a set of abscissas and weights retain the physical solution and allow for the construction of moments that generate a set of partial differential equations (PDE's). QBMM has shown promising preliminary results for modeling granular gases or dispersed phases within carrier fluids and offers an alternative to Lagrangian methods such as Discrete Particle Simulation (DPS). The Lattice Boltzmann Method (LBM) shares some strong similarities in concept, but it relies on fixed abscissas whereas quadrature-based methods are more adaptive. Additionally, the Navier–Stokes equations(N-S) can be derived from the moment method approach.

The governing equations of a mathematical model describe how the values of the unknown variables change when one or more of the known variables change.