History

In 1134 a storm broke through the Flemish coast and created the tidal inlet the Zwin. It made Bruges the only Flemish cloth town with access to the North Sea. Bruges' first port was Damme and water transport could reach Bruges over the river Reie and other channels. [1] : 132

Beginning of Hanseatic trade

Traders from cities that later made up the Hanseatic League seem to have come to Bruges from the first half of the 13th century. The traders didn't acquire any real estate to establish themselves, but rented lodging and storage from locals. The canteen of the Carmelite monastery, where the Hansards went to church, could be rented for meetings if it was necessary. [2] : 92 In 1252 countess Margaret of Flanders and her son Guy of Flanders granted two sets of privileges to Holy Roman traders, one to a group based around Hamburg and one to a Rhenish-Westphalian grouping including Cologne. The latter requested an emporium-enclave near Damme, but this was fatefully denied: Bruges wanted to secure a key position over nearby towns and villages and couldn't use new potential rivals. [3] : 182–183

Conflict arose in the late 1270s about irregularities in weighing and the increase of certain duties. Not only the Hanse objected, but also Spanish and south French merchants. The League moved the kontor temporarily to Aardenburg in 1280, supported by the count of Flanders. It was however an unfavourable location. Lübeck seems to have played a prime role in the negotiations that began in 1281. The kontor returned in 1282. [4] : 58 [5] : 19–21

A progressive process of silting up the Zwin began in the 13th century. [1] : 132

It was impossible for larger ships to call at Damme anymore by the 14th century, the port for these ships moved to Sluis. Bruges made large investments in an ultimately vain effort to keep the trade route open. [1] : 132

New complaints arose about weighing and monetary issues in 1307 or 1308. Again Aardenburg and the count of Flanders facilitated a temporary relocation of the kontor. Brunswick, Goslar and Magdeburg led negotiations. The kontor returned in 1310, the Hansards acquired the right to their own meetings and to issue and enforce internal ordinances. [5] : 20–21

Reform of the kontor and height of the kontor's influence

The Kontor of Bruges was institutionally reformed in 1347, in a way that would be very influential. It pioneered a division of Hansards in three parts, a reform that would be adopted by Hanseatic League itself and by the Steelyard in London. [2] : 101

Again concerns about weighing, arbitrary tax increases, compensations and privileges moved the League in 1350 to relocate the kontor to Aardenburg, against the backdrop of the Hundred Years' War, but this wasn't carried out. A diet convened in 1356 to discuss the matter but negotiations led nowhere. The Hanseatic diet called a blockade against Flanders in January 1358. [6] : 28-29 Duke Albert I of Bavaria, Hainaut, Holland and Zeeland offered attractive terms, and the kontor was moved to Dordt in May 1358. The blockade nearly caused a famine despite imperfect compliance by the Hansards. Count Louis II extended Hanseatic privileges to the whole of Flanders. [7] : 67–68

But the context of the Hundred Years' War made it difficult for Bruges to keep the generous terms of the agreement and customs were raised. An attempt to move the kontor out in the winter 1377/1378 failed. Count Louis II supported Bruges. Worserning war conditions and a revolt in Ghent drove the merchants away, so few were around at the time of the Battle of Roosebeke. Louis died in 1384 and the League opened negotiations with the new count, Philip the Bold. Excessive demands by the Hanse's representatives made negotiations fail. The kontor temporarily moved to Dordrecht in 1388, again invited by Albert I. A total Hanseatic embargo was placed on Flanders, it was only lightened in 1389 to allow the Teutonic Order to sell amber. Intervention by the Prussian towns and the grand master of the Teutonic Knights enabled a resolution in late 1391. The Hanseatic privileges were restored and the merchants received a large compensation. [7] : 80–81

Beginning of decline

Bruges' importance for Hanseatic trade fell quickly after the embargo was resolved in 1392, [3] : 187 especially affecting the cloth trade. Hansards began to look for other sources, like England. [1] : 143

After 1390 Europe faced its first great scarcity of precious metal in centuries. The council of Bruges became convinced that the shortage was caused by hoarding by foreign merchants and issued an ordinance in September 1399 that required that credit was paid in cash with increasing shares of gold from 1 May 1400 and reaching full force on 1 January 1401. The ordinance caused an acute shortage of cash and made credit volatile in Bruges. The Kontor of Bruges and Lübeck cooperated to instate a total ban on credit for Hanseatic traders on Flanders for 3 years from 2 July 1401. [8] : 82

When Philip the Good, duke of Burgundy and overlord of Bruges, switched sides to France in the Hundred Years' War with the Treaty of Arras, political attitudes changed. Accused of English loyalties, 80 German merchants were killed in June 1436 at Sluis. The kontor was moved to Antwerp and a blockade again created a famine in Bruges, and the kontor returned after a renewal of the privileges. [7] : 92

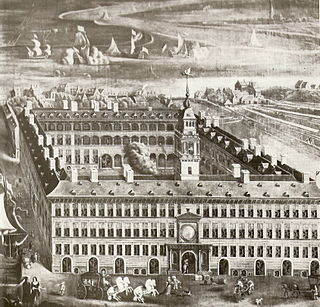

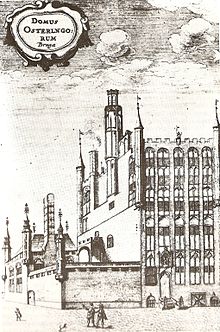

Construction of kontor buildings

The Hansards rented the Oosterlingenhuis ("Easterling house", it refers to Germans) from 1442 as their own guildhall. In 1478 its new guildhall buildings at the Oosterlingenplein were completed. But the kontor continued to use the canteen of the monastery of the Carmelite order. [1] : 139–140 The monastery hasn't survived, while the façade of the Oostenlingenhuis doesn't exist anymore. [3] : 181, 184

Renewed complaints about breaches against privileges motivated the Hanseatic League to increase the economic power of the staple by expanding it. However it didn't resolve the issues and the kontor was relocated again. The destination would first be Deventer, but the Hanse decided for Utrecht in the end. Philip the Good occupied Utrecht in 1455. Negotiations resulted in the kontor's return in August 1457 with little gain. Merchants widely ignored the embargo and it would be the last Hanseatic embargo against Flanders. [7] : 92 [3] : 188

Further decline and end

By the middle 15th century the closing up of the Zwin was starting to seriously harm Bruges' trade. [1] : 132

Trade has deteriorated so much in the 16th century from the Zwin's closure that the Hanseatic League decided to move the kontor to Antwerp in 1520. The Oostershuis, completed about 1560, was built for it. [1] : 132