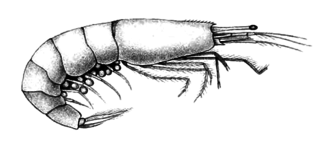

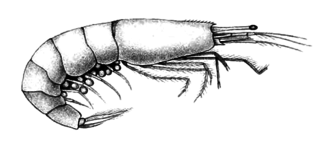

Dendrobranchiata is a suborder of decapods, commonly known as prawns. There are 540 extant species in seven families, and a fossil record extending back to the Devonian. They differ from related animals, such as Caridea and Stenopodidea, by the branching form of the gills and by the fact that they do not brood their eggs, but release them directly into the water. They may reach a length of over 330 millimetres (13 in) and a mass of 450 grams (1.0 lb), and are widely fished and farmed for human consumption.

Malacostraca is the second largest of the six classes of pancrustaceans just behind hexapods, containing about 40,000 living species, divided among 16 orders. Its members, the malacostracans, display a great diversity of body forms and include crabs, lobsters, crayfish, shrimp, krill, prawns, woodlice, amphipods, mantis shrimp, tongue-eating lice and many other less familiar animals. They are abundant in all marine environments and have colonised freshwater and terrestrial habitats. They are segmented animals, united by a common body plan comprising 20 body segments, and divided into a head, thorax, and abdomen.

Isopoda is an order of crustacean, which includes woodlice and their relatives. Members of this group are called Isopods and include both terrestrial and aquatic species. All have rigid, segmented exoskeletons, two pairs of antennae, seven pairs of jointed limbs on the thorax, and five pairs of branching appendages on the abdomen that are used in respiration. Females brood their young in a pouch under their thorax.

Bioturbation is defined as the reworking of soils and sediments by animals or plants. It includes burrowing, ingestion, and defecation of sediment grains. Bioturbating activities have a profound effect on the environment and are thought to be a primary driver of biodiversity. The formal study of bioturbation began in the 1800s by Charles Darwin experimenting in his garden. The disruption of aquatic sediments and terrestrial soils through bioturbating activities provides significant ecosystem services. These include the alteration of nutrients in aquatic sediment and overlying water, shelter to other species in the form of burrows in terrestrial and water ecosystems, and soil production on land.

Gilvossius tyrrhenus is a species of thalassinidean crustacean which grows to a length of 70 mm (2.8 in). It lives in burrows in shallow sandy parts of the sea-bed in the Mediterranean Sea and northern Atlantic Ocean. It is the most common thalassinidean in the Mediterranean, and has been used as bait by fishermen for at least 200 years.

Bodotriidae is a family of crustaceans belonging to the order Cumacea. Bodotriids have a worldwide distribution in shallow and deep waters. There are over 380 described species in over 30 genera, being the most diverse cumacean family. Their external morphology differs from other cumaceans by a combination of traits that independently are not unique to the family: the telson is fused to the last abdominal segment, the dorsal part of the mandible has a boat shape (naviculoid), exopods exist on the third maxilliped and the first peraeopod, and there is a uropodal endopod with one or two articles.

Gynodiastylidae is one of the eight most commonly recognised families of crustaceans of the order Cumacea. They are especially prevalent in the southern hemisphere, with some types described from Japan, Thailand and the Persian Gulf. Most are found at less than 100 metres (330 ft) depth.

Nototropis falcatus is a species of amphipod crustacean. It is whitish in colour, with brown patches, and grows to a total length of around 7 mm (0.3 in). It lives on soft sediment such as fine sand at depths of 10 to 50 metres, from northern Norway to the west coast of Ireland, including the North Sea, and as far south as the southern Bay of Biscay.

Neoglyphea inopinata is a species of glypheoid lobster, a group thought long extinct before Neoglyphea was discovered. It is a lobster-like animal, up to around 15 centimetres (5.9 in) in length, although without claws. It is only known from 17 specimens, caught at two sites – one at the entrance to Manila Bay in the Philippines, and one in the Timor Sea, north of Australia. Due to the small number of specimens available, little is known about the species, but it appears to live up to five years, with a short larval phase. A second species, previously included in Neoglyphea, is now placed in a separate genus, Laurentaeglyphea.

A shrimp is a crustacean with an elongated body and a primarily swimming mode of locomotion – typically belonging to the Caridea or Dendrobranchiata of the order Decapoda, although some crustaceans outside of this order are also referred to as "shrimp".

Synalpheus microneptunus is a species of small snapping shrimp native to the waters off the island of Barbados. It is one of at least seven known species of eusocial shrimp. They are cryptofauna, living exclusively within the network of tunnels in the sponges Neopetrosia proxima and Neopetrosia subtriangularis. They form small colonies of six to fifteen individuals, usually with only a single breeding female.

Ogyrides, also known as long eyed shrimps, is a genus of decapod crustaceans consisting of 13 species. It is the only genus in the monotypic family Ogyrididae.

Belzebub is a genus of prawns in the family Luciferidae. The species which make up the genus Belzebub were formerly placed in the genus Lucifer but were separated to form Belzebub after a cladistic analysis. They are very small planktonic and benthic prawns with an extreme lateral compression of the carapace with elongated mandibles and anteriors of the pereiopods but lacking pereiopods 4 and 5 and any gills. The pereiopods either lack chelae or they are substantially reduced. The sixth abdominal segment of males has two ventral processes and the telson has a strong ventral process.

Mark Alexander Lever is a microbial ecologist and biogeochemist who studies the role of microorganisms in the global carbon cycle. He is a professor of biogeochemistry and geobiology at the Marine Science Institute of the University of Texas at Austin.

Munida quadrispina is a species of squat lobster. It was originally described to science by James E. Benedict in 1902. This and other species of squat lobsters are sometimes referred to as "pinch bugs".

Heteromysis is a genus of marine mysid crustaceans from the family Mysidae, associated with various shallow-water invertebrates. The name describes differentiation of its pereiopods as possible adaptation to commensal life-style. Heteromysis is one of the largest mysid genera, containing more than 100 species. The genus is distributed globally, but predominantly in tropical and subtropical waters.

Armadillidium jerrentrupi is a European species of woodlouse endemic to Greece. It is a relatively medium-sized species that probably belongs to the so-called "Armadillidium fossuligerum complex".

Boreomysis inopinata is a species of mysid crustaceans from the subfamily Boreomysinae. It is also a member of the nominotypical subgenus Boreomysis sensu stricto. The species is a deepwater bathypelagic mysid, found only from the Tasman Sea off Australia.

Boreomysis sphaerops is a species of mysid crustaceans from the subfamily Boreomysinae. It is also a member of the nominotypical subgenus Boreomysis sensu stricto. The species is a meso-bathypelagic mysid, distributed in the West Indo-Pacific, although known only from few records off Japan and Australia.

Boreomysis urospina is a species of mysid crustacean from the subfamily Boreomysinae. It is also a member of the subgenus Petryashovia. The species is a mesopelagic mysid, found only in the Tasman Sea, off Australia.