A pink triangle has been a symbol for the LGBT community, initially intended as a badge of shame, but later reclaimed as a positive symbol of self-identity. In Nazi Germany in the 1930s and 1940s, it began as one of the Nazi concentration camp badges, distinguishing those imprisoned because they had been identified by authorities as gay men. In the 1970s, it was revived as a symbol of protest against homophobia, and has since been adopted by the larger LGBT community as a popular symbol of LGBT pride and the LGBT movements and queer liberation movements.

The LGBT community is a loosely defined grouping of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals united by a common culture and social movements. These communities generally celebrate pride, diversity, individuality, and sexuality. LGBT activists and sociologists see LGBT community-building as a counterweight to heterosexism, homophobia, biphobia, transphobia, sexualism, and conformist pressures that exist in the larger society. The term pride or sometimes gay pride expresses the LGBT community's identity and collective strength; pride parades provide both a prime example of the use and a demonstration of the general meaning of the term. The LGBT community is diverse in political affiliation. Not all people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender consider themselves part of the LGBT community.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Austria have advanced significantly in the 21st century, and are now considered among the most developed in the world. Both male and female same-sex sexual activity are legal in Austria. Registered partnerships were introduced in 2010, giving same-sex couples some of the rights of marriage. Stepchild adoption was legalised in 2013, while full joint adoption was legalised by the Constitutional Court of Austria in January 2015. On 5 December 2017, the Austrian Constitutional Court decided to legalise same-sex marriage, and the ruling went into effect on 1 January 2019.

New Zealand society is generally accepting of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) peoples. The LGBT-friendly environment is epitomised by the fact that there are several members of Parliament who belong to the LGBT community, LGBT rights are protected by the Human Rights Act, and same-sex couples are able to marry as of 2013. Sex between men was decriminalised in 1986. New Zealand has an active LGBT community, with well-attended annual gay pride festivals in most cities.

James Willis Toy was a long-time American activist and a pioneer for LGBT rights in Michigan.

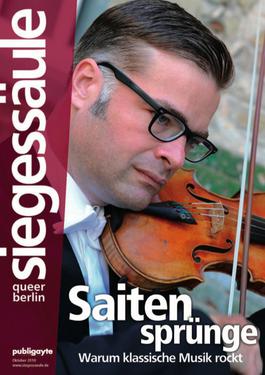

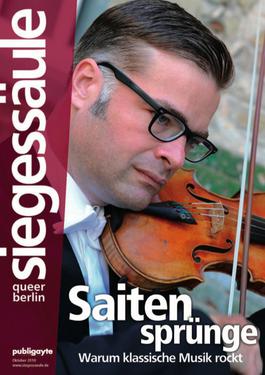

Siegessäule is Berlin's most widely distributed queer magazine and has been published monthly, except for two brief hiatuses, since April 1984. Originally only available in West Berlin, it ran with the subtitle "Berlin's monthly page for Gays". In 1996, it was broadened to include lesbian content, and in 2005 it was expanded to reach a wider queer target base, becoming the only magazine of its scale in Europe to represent the full spectrum of the LGBT community. The magazine is available for free at around 700 locations in Berlin, printing 53.688 copies per month. Since March-issue 2013, it has been overseen by chief editor Jan Noll.

The Australian Queer Archives (AQuA) is a community-based non-profit organisation committed to the collection, preservation and celebration of material reflecting the lives and experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex LGBTI Australians. It is located in Melbourne. The Archives was established as an initiative of the 4th National Homosexual Conference, Sydney, August 1978, drawing on the previous work of founding President Graham Carbery. Since its establishment the collection has grown to over 200,000 items, constituting the largest and most significant collection of material relating to LGBT Australians and the largest collection of LGBT material in Australia, and the most prominent research centre for gay, lesbian, bisexual, trans and intersex history in Australia.

Switzerland, a country which has long held a stance of neutrality in its relations with other nations, has not been immune to the movement of equality for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender citizens. Prior to the 20th century, sodomy and other types of sexual intercourse between people of the same sex was held in various levels of legal contempt. Today, the modern LGBT rights movement in Switzerland is related to the larger international movement which developed largely after 1969.

Christian Michelides is an Austrian psychotherapist. He is the director of Lighthouse Wien.

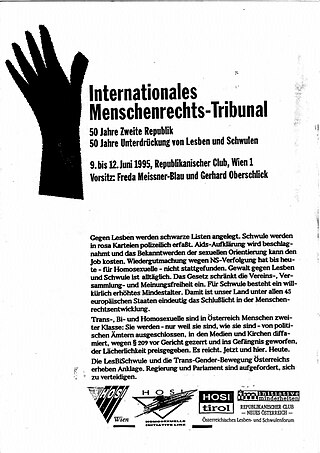

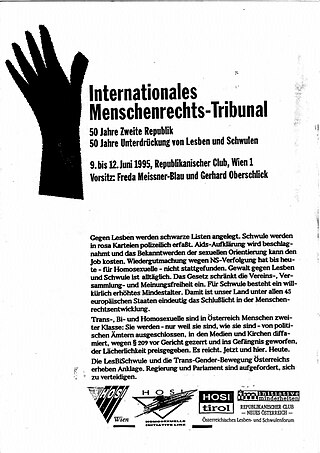

The International Human Rights Tribunal (IHRT) was a symbolic tribunal which took place in Vienna, Austria, in June 1995. It was chaired by environmental and human rights activist Freda Meissner-Blau and Gerhard Oberschlick, editor of FORVM, and was dedicated to the persecution of lesbians, gays, bisexuals and transgender persons in Austria from 1945 to 1995.

The Austrian Lesbian and Gay Forum (ALGF), in German: Österreichisches Lesben- und Schwulenforum (ÖLSF), was the driving force in Austria's LGBT movement in the 1990s and has founded Austria's only Christopher Street Day (CSD) parade, called Regenbogenparade, on Vienna's Ringstrasse in 1996.

Homosexuality has been legal in Poland since 1932. However, homosexuality has been a taboo subject for most of Poland's history, and that and the lack of legal discrimination have often led to a lack of historical sources on the subject. Homophobia has been a common public attitude in Poland because of the influence of Catholic Church in Polish public life and the widespread social conservatism in Poland. Homosexuality in Poland was decriminalized in 1932, but criminalized following the 1939 Soviet and Nazi Invasion.

Chennai has LGBTQIA cultures that are diverse concerning- socio-economic class, gender, and degree of visibility and politicisation. They have historically existed in the margins and surfaced primarily in contexts such as transgender activism and HIV prevention initiatives for men having sex with men (MSM) and trans women (TG).

The lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community in San Francisco is one of the largest and most prominent LGBT communities in the United States, and is one of the most important in the history of American LGBT rights and activism alongside New York City. The city itself has been described as "the original 'gay-friendly city'". LGBT culture is also active within companies that are based in Silicon Valley, which is located within the southern San Francisco Bay Area.

Berlin was the capital city of the German Empire from 1871 to 1945, its eastern part the de facto capital of East Germany from 1949 to 1990, and has been the capital of the unified Federal Republic of Germany since June, 1991. The city has an active LGBT community with a long history. Berlin has many LGBTIQ+ friendly districts, though the borough of Schöneberg is widely viewed both locally and by visitors as Berlin's gayborhood. Particularly the boroughs North-West near Nollendorfplatz identifies as Berlin's "Regenbogenkiez", with a certain concentration of gay bars near and along Motzstraße and Fuggerstraße. Many of the decisive events of what has become known as Germany's second LGBT movement take place in the West Berlin boroughs of Charlottenburg, Schöneberg, and Kreuzberg beginning in 1971 with the formation of the Homosexuelle Aktion Westberlin (HAW). Where as in East Berlin the district of Prenzlauer Berg became synonymous with the East Germany LGBT movement beginning in 1973 with the founding of the HIB. Schöneberg's gayborhood has a lot to offer for locals and tourists alike, and caters to, and is particularly popular with gay men. Berlin's large LGBT events such as the Lesbian and Gay City Festival, East Berlin Leather and Fetish Week, Folsom Europe, and CSD center around Schöneberg, with related events taking place city-wide during these events. Nevertheless, with roughly 180 years of LGBTIQ+ history, and a very large community made up of members with very varied biographies, it is hard to find a place in Berlin completely without LGBT culture past or present. Berlin's present-day neighborhoods with a certain concentration of LGBTIQ+ oriented culture vary somewhat in terms of history, demography, and where the emphasis in each neighborhoods' queer culture falls along the LGBTIQ+ spectrum. Over the course of its nearly two centuries of queer history (herstory), definitions not with standing, Berlin's LGBTIQ+ culture has never ceased to change, not only in appearance and self-understanding, but also in where the centers of queer culture were located in the city. What is true about Berlin's "LGBT culture in Berlin" at one point in time, in a given place and from a given perspective, is almost certainly different the next.

D.C.Black Pride is the first official black gay pride event in the United States and one of two officially recognized festivals for the African-American LGBT community. It is a program of the Center for Black Equity (CBE) and is also affiliated with the Capital Pride Alliance. DC Black Pride is held annually on Memorial Day weekend.

Vienna Pride is a celebration that takes place in the Austrian capital every year in support of equality for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people. It includes the Austrian pride parade, the Rainbow Parade (Regenbogen-Parade) which takes place on the Vienna Ring Road, (Ringstraße), at the end of the festival.

The Homosexual Initiative Vienna (HOSI Wien) was founded in Vienna in 1979. It is Austria's oldest and largest gay, lesbian and bisexual association. It is a member-based organisation holding an annual general meeting and board elections. The organisation supports several sub groups including a youth group and women's group. It organises the annual Vienna Pride and Rainbow Parade.

Rosa Lila Villa is an Austrian LGBT center situated in the Linke Wienzeile Buildings neighbourhood of Vienna. It is designed as a housing project, restaurant, event and counseling venue for LGBT people in Austria.