Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Ukraine face legal and social challenges not experienced by non-LGBT individuals; historically, the prevailing social and political attitudes have been intolerant of LGBT people, and strong evidence suggests this attitude remains in parts of the wider society. Since the fall of the Soviet Union and Ukraine's independence in 1991, the Ukrainian LGBT community has gradually become more visible and more organized politically, organizing several LGBT events in Kyiv, Odesa, Kharkiv, and Kryvyi Rih.

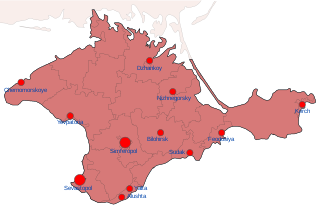

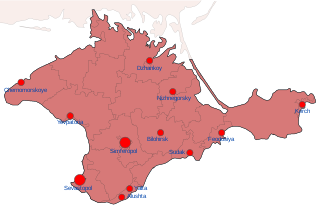

Simeiz is a resort town, an urban-type settlement in Yalta Municipality in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, a territory recognized by a majority of countries as part of Ukraine and incorporated by Russia as the Republic of Crimea. Its name is of Greek origin. The town is located by the southern slopes of the main range of Crimean Mountains at the base of Mount Kosh-Kaya, 18 kilometers (11 mi) west from Yalta. Population: 2,604 .

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Kazakhstan face significant challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Both male and female kinds of same-sex sexual activity are legal in Kazakhstan, but same-sex couples and households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available to opposite-sex married couples.

Ukraine does not recognize same-sex marriage or civil unions. The Constitution of Ukraine defines marriage as between "a woman and a man". The issue of legal recognition for same-sex couples has become particularly acute after the start of Ukraine's accession to the European Union in 2022 and the Russian large-scale invasion of Ukraine during the Russo-Ukrainian War.

The Belarusian LGBT Human Rights Project GayBelarus is a national youth civic association. They operate the Jáhada positive queer infoportal.

Milliy Fırqa is a pro-Russian Crimean Tatar non-government organization founded in 2006. Its name is taken from the former party Milliy Fırqa which was banned by the Soviet authorities in 1921. The current leader is Vasvi Abduraimov.

Lake Donuzlav, also referred to as Donuzlav Bay, is the deepest lake of Crimea and biggest in Chornomorske Raion. It is a protected landscape and recreational park of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea.

Russian intelligentsia expressed various reactions to the Russian annexation of Crimea.

Insight is a Ukrainian LGBTQI organization. Unlike most Ukrainian LGBT organizations focused on work with gay men and MSM, Insight’s priority is to help lesbians, bisexual women, transgender, queer and intersex people. Insight is one of the few public organizations in working with transgender people.

The 22nd Army Corps is a corps of the coastal defence troops of the Black Sea Fleet of the Russian Navy. Formed in 2017 after the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation, the corps is headquartered in Simferopol and controls units based in Crimea.

Ruslan Ismailovich Balbek is a Russian and former Ukrainian politician and former member of the State Duma from the United Russia party. A supporter of the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation, he has been highly critical of the Mejlis.

The Tashkent Ten were ten Crimean Tatar civil rights activists tried in Tashkent by the Uzbek Supreme Court from 1 July to 5 August 1969. The trial was sometimes called the Tashkent Process.

Rustem Enverovych Umerov is a Ukrainian politician, businessman, investor, philanthropist and the current Defence Minister of Ukraine. Umerov is a Muslim, and of Crimean Tatar origin.

2022 in Russia is the 31st year of the Russian Federation.

Luhansk People's Republic–Russia relations were bilateral relations between Russia and the Luhansk People's Republic (LPR). The LPR is widely internationally unrecognized, with most of the international community regarding the LPR as a Russian military occupation of a portion of Ukraine's Luhansk Oblast. The LPR was annexed by Russia on 30 September 2022; the LPR authorities willingly acceded to Russia, and the annexation is widely internationally unrecognized. From April 2014 to September 2022, the LPR portrayed itself as an independent state, and it was widely regarded as a puppet state of Russia by the international community.

Olena Olehivna Shevchenko is a Ukrainian women's and LGBT rights activist. After working as a teacher, she co-founded the NGO Insight in 2007 to advocate for LGBT inclusiveness on feminist platforms. She started annual events including Women's Day March, Transgender Day of Remembrance and the Festival of Equality, to protest against discrimination against women and the LGBT community in Ukraine and in other former Soviet countries. Her opponents have repeatedly attacked her and her events.

In late September 2022, in the context of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russian-installed officials in Ukraine staged so-called referendums on the annexation of occupied territories of Ukraine by Russia. They were widely described as sham referendums by commentators and denounced by various countries. The validity of the results of the referendums has been accepted by North Korea, and no other sovereign state.

The general mobilization in the Donetsk People's Republic and the Luhansk People's Republic began on 19 February 2022, 5 days before the start of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Tens of thousands of local residents were forcibly mobilized for the war.

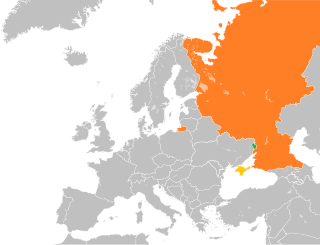

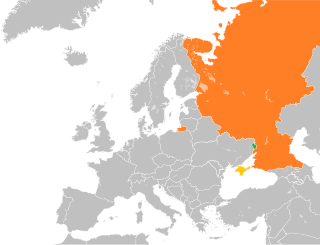

On 27 February 2014, unmarked Russian soldiers were deployed to the Crimean Peninsula in order to wrest control of it from Ukraine, triggering the Russo-Ukrainian War. This military occupation, which the Ukrainian government considers to have begun on 20 February, laid the foundation for the Russian annexation of Crimea on 18 March 2014. Under Russia, the Ukrainian Autonomous Republic of Crimea was replaced by the Republic of Crimea, though the legitimacy of the latter is scarcely recognized internationally.

Donuzlav is an air base near Lake Donuzlav in Crimea, Ukraine. The air base was decommissioned in 1995, but has been claimed to have been revived by the Russian military since the Russo-Ukrainian war.

![Marchers at the KyivPride [uk] event in 2019 IAN76774.jpg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/81/IAN76774.jpg/220px-IAN76774.jpg)