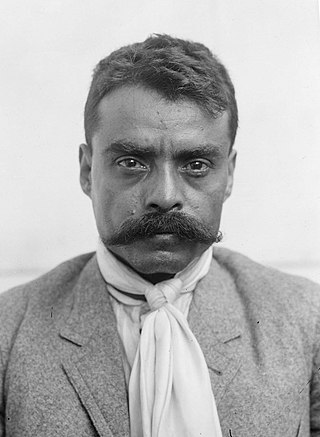

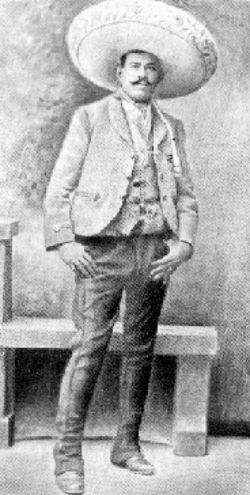

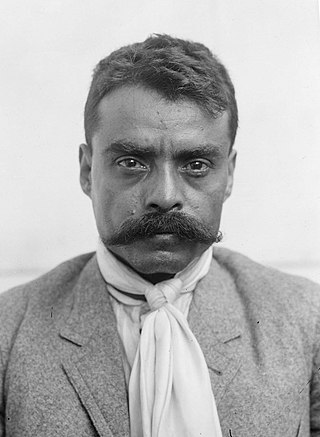

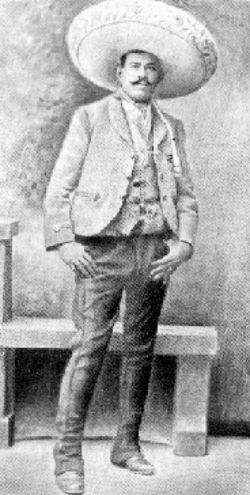

Emiliano Zapata Salazar was a Mexican revolutionary. He was a leading figure in the Mexican Revolution of 1910–1920, the main leader of the people's revolution in the Mexican state of Morelos, and the inspiration of the agrarian movement called Zapatismo.

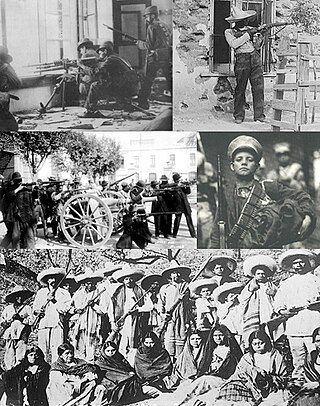

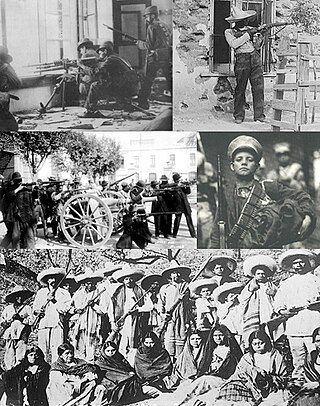

The Mexican Revolution was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from 20 November 1910 to 1 December 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history". It resulted in the destruction of the Federal Army and its replacement by a revolutionary army, and the transformation of Mexican culture and government. The northern Constitutionalist faction prevailed on the battlefield and drafted the present-day Constitution of Mexico, which aimed to create a strong central government. Revolutionary generals held power from 1920 to 1940. The revolutionary conflict was primarily a civil war, but foreign powers, having important economic and strategic interests in Mexico, figured in the outcome of Mexico's power struggles; the U.S. involvement was particularly high. The conflict led to the deaths of around one million people, mostly noncombatants.

La Cucaracha is a popular Mexican folk song about a cockroach who cannot walk. The song's origins are unclear, but it dates back at least to the 1910s during the Mexican Revolution. The song belongs to the Mexican corrido genre. The song's melody is widely known and there are many alternative stanzas.

The military history of Mexico encompasses armed conflicts within that nation's territory, dating from before the arrival of Europeans in 1519 to the present era. Mexican military history is replete with small-scale revolts, foreign invasions, civil wars, indigenous uprisings, and coups d'état by disgruntled military leaders. Mexico's colonial-era military was not established until the eighteenth century. After the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire in the early sixteenth century, the Spanish crown did not establish on a standing military, but the crown responded to the external threat of a British invasion by creating a standing military for the first time following the Seven Years' War (1756–63). The regular army units and militias had a short history when in the early 19th century, the unstable situation in Spain with the Napoleonic invasion gave rise to an insurgency for independence, propelled by militarily untrained, darker complected men fighting for the independence of Mexico. The Mexican War of Independence (1810–21) saw royalist and insurgent armies battling to a stalemate in 1820. That stalemate ended with the royalist military officer turned insurgent, Agustín de Iturbide persuading the guerrilla leader of the insurgency, Vicente Guerrero, to join in a unified movement for independence, forming the Army of the Three Guarantees. The royalist military had to decide whether to support newly independent Mexico. With the collapse of the Spanish state and the establishment of first a monarchy under Iturbide and then a republic, the state was a weak institution. The Roman Catholic Church and the military weathered independence better. Military men dominated Mexico's nineteenth-century history, most particularly General Antonio López de Santa Anna, under whom the Mexican military were defeated by Texas insurgents for independence in 1836 and then the U.S. invasion of Mexico (1846–48). With the overthrow of Santa Anna in 1855 and the installation of a government of political liberals, Mexico briefly had civilian heads of state. The Liberal Reforms that were instituted by Benito Juárez sought to curtail the power of the military and the church and wrote a new constitution in 1857 enshrining these principles. Conservatives comprised large landowners, the Catholic Church, and most of the regular army revolted against the Liberals, fighting a civil war. The Conservative military lost on the battlefield. But Conservatives sought another solution, supporting the French intervention in Mexico (1862–65). The Mexican army loyal to the liberal republic were unable to stop the French army's invasion, briefly halting it in with a victory at Puebla on 5 May 1862. Mexican Conservatives supported the installation of Maximilian Hapsburg as Emperor of Mexico, propped up by the French and Mexican armies. With the military aid of the U.S. flowing to the republican government in exile of Juárez, the French withdrew its military supporting the monarchy and Maximilian was caught and executed. The Mexican army that emerged in the wake of the French Intervention was young and battle tested, not part of the military tradition dating to the colonial and early independence eras.

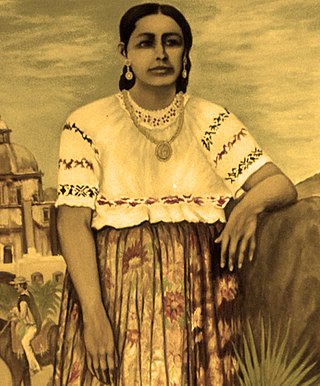

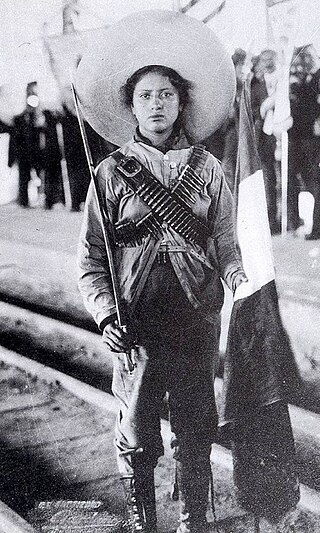

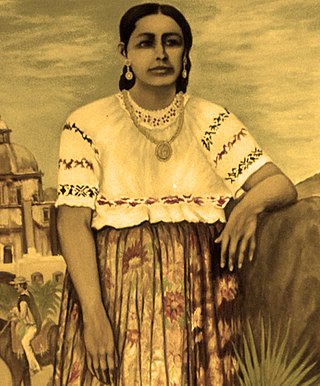

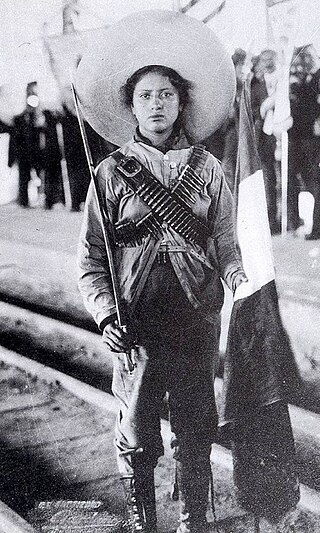

Soldaderas, often called Adelitas, were women in the military who participated in the conflict of the Mexican Revolution, ranging from commanding officers to combatants to camp followers. "In many respects, the Mexican revolution was not only a men's but a women's revolution." Although some revolutionary women achieved officer status, coronelas, "there are no reports of a woman achieving the rank of general." Since revolutionary armies did not have formal ranks, some women officers were called generala or coronela, even though they commanded relatively few men. A number of women took male identities, dressing as men, and being called by the male version of their given name, among them Ángel Jiménez and Amelio Robles Ávila.

Camp followers are civilians who follow armies. There are two common types of camp followers; first, the spouses and children of soldiers, who follow their spouse or parent's army from place to place; the second type of camp followers have historically been informal army service providers, servicing the needs of encamped soldiers, in particular selling goods or services that the military does not supply—these have included cooking, laundering, liquor, nursing, sexual services and sutlery.

Las Adelitas de Aztlán was a short-lived Mexican American female civil rights organization that was created by Gloria Arellanes and Gracie and Hilda Reyes in 1970. Gloria Arellanes and Gracie and Hilda Reyes were all former members of the Brown Berets, another Mexican American Civil rights organization that had operated concurrently during the 1960s and 1970s in the California area. The founders left the Brown Berets due to enlarging gender discrepancies and disagreements that caused much alienation amongst their female members. The Las Adelitas De Aztlan advocated for Mexican-American Civil rights, better conditions for workers, protested police brutality and advocated for women's rights for the Latino community. The name of the organization was a tribute to Mexican female soldiers or soldaderas that fought during the Mexican Revolution of the early twentieth century.

Adelita or Adelitas may refer to:

The Soldiers of Pancho Villa is a 1959 Mexican epic historical drama film co-written, produced, and directed by Ismael Rodríguez, inspired by the popular Mexican Revolution corrido "La Cucaracha". It stars María Félix and Dolores del Río in the lead roles, and features Emilio Fernández, Antonio Aguilar, Flor Silvestre, and Pedro Armendáriz in supporting roles.

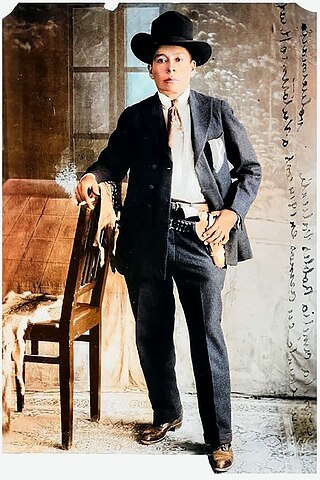

Amador Salazar Jiménez was a Mexican military leader who participated in the Mexican Revolution.

Margarita Neri was a Zapatista commander and a soldadera during the Mexican Revolution. She was a Dutch-Maya Indian from the Mexican state of Quintana Roo who was one of the few female military leaders to achieve fame during the revolution. Neri is said to have led over one thousand soldiers in 1910 through Mexico just as if she were a man earning the utmost respect of Zapata. She commanded Zapatista forces through the Tabasco and Chiapas region during the early stages of the Mexican Revolution, and It is rumored that she once declared her intention to behead Porfirio Diaz personally.

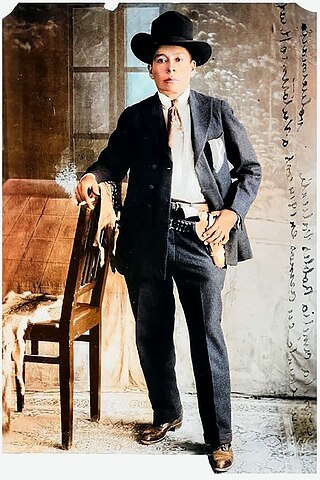

Amelio Robles Ávila was a colonel during the Mexican Revolution. Assigned female at birth with the name Amelia Robles Ávila, Robles lived openly as a man from age 24 until his death at age 95.

Antonia Nava de Catalán was a heroine of the Mexican War of Independence. She accompanied her husband, a volunteer who rose to the rank of colonel, throughout the war. Three of her sons were killed in the struggle. She is remembered for her willingness to sacrifice her family and herself to achieve independence from Spain, and came to be known as "La Generala". She fought alongside Jose Maria Morales until her death.

Petra Herrera, also known as "Pedro Herrera" was a Mexican "soldadera".

The struggle for women's right to vote in Mexico dates back to the nineteenth century, with the right being achieved in 1953.

Ángela Jiménez, alias Lieutenant Ángel was a soldadera during the Mexican Revolution. She performed different duties such as a flag bearer, spy and sometimes cook. She was also an expert in explosives.

Valentina Ramírez Avitia was a Mexican revolutionary and soldadera. She was known as "La Valentina" and "La leona de Norotal". She fought against the Federales in the Mexican Revolution at a time when women were not allowed to join the army. Her parallels to the story of Hua Mulan lead to her modern nickname of "The Mexican Mulan".

Florinda Lazos León was a Mexican revolutionary, journalist, politician and suffragist.

Adela Velarde Pérez was a Mexican activist who fought in the Mexican Revolution.