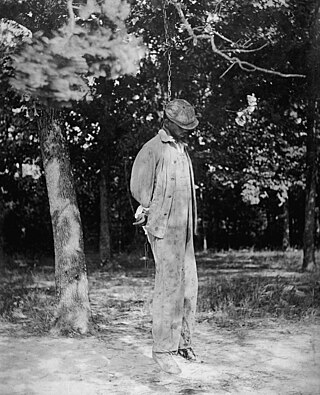

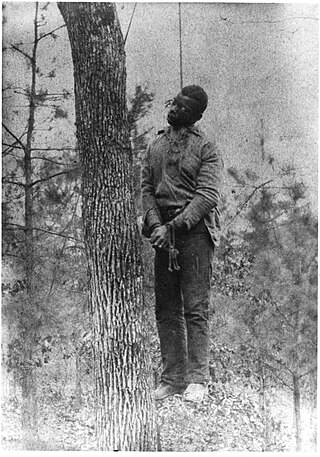

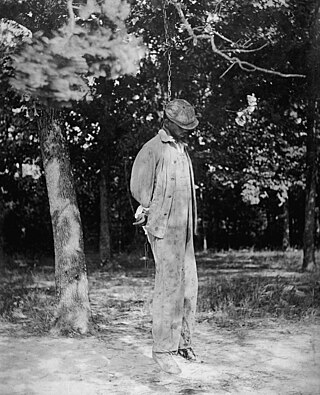

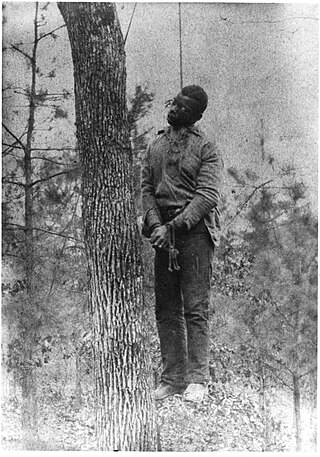

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an extreme form of informal group social control, and it is often conducted with the display of a public spectacle for maximum intimidation. Instances of lynchings and similar mob violence can be found in every society.

The Texas Ranger Division, also known as the Texas Rangers and also known as Diablos Tejanos, is an investigative law enforcement agency with statewide jurisdiction in the U.S. state of Texas. It is based in the capital city Austin. In the time since its creation, the Texas Rangers have investigated crimes ranging from murder to political corruption, acted in riot control and as detectives, protected the governor of Texas, tracked down fugitives, served as a security force at important state locations, including the Alamo, and functioned as a paramilitary force at the service of both the Republic (1836–1846) and the State of Texas.

Mexican American history, or the history of American residents of Mexican descent, largely begins after the annexation of Northern Mexico in 1848, when the nearly 80,000 Mexican citizens of California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico became U.S. citizens. Large-scale migration increased the U.S.' Mexican population during the 1910s, as refugees fled the economic devastation and violence of Mexico's high-casualty revolution and civil war. Until the mid-20th century, most Mexican Americans lived within a few hundred miles of the border, although some resettled along rail lines from the Southwest into the Midwest.

Lynching was the widespread occurrence of extrajudicial killings which began in the United States' pre–Civil War South in the 1830s and ended during the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s. Although the victims of lynchings were members of various ethnicities, after roughly 4 million enslaved African Americans were emancipated, they became the primary targets of white Southerners. Lynchings in the U.S. reached their height from the 1890s to the 1920s, and they primarily victimized ethnic minorities. Most of the lynchings occurred in the American South, as the majority of African Americans lived there, but racially motivated lynchings also occurred in the Midwest and border states. In 1891, the largest single mass lynching in American history was perpetrated in New Orleans against Italian immigrants.

Francis Augustus Hamer was an American lawman and Texas Ranger who led the 1934 posse that tracked down and killed criminals Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow. Renowned for his toughness, marksmanship, and investigative skill, he acquired status in the Southwest as the archetypal Texas Ranger. He was inducted into the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame. His professional record and reputation are controversial, particularly with regard to his willingness to use extrajudicial killing even in an increasingly modernized society.

Anti-Mexican sentiment, is prejudice, fear, discrimination, or hatred towards Mexico and people of Mexican descent, Mexican culture and/or Mexican Spanish. It is most commonly found in the United States.

The origins of today's Texas Ranger Division trace back to the first days of Anglo-American settlement of what is today the State of Texas, when it was part of the Province of Coahuila y Tejas belonging to the newly independent country of Mexico. The unique characteristics that the Rangers adopted during the force's formative years and that give the division its heritage today—characteristics for which the Texas Rangers would become world-renowned—have been accounted for by the nature of the Rangers' duties, which was to protect a thinly populated frontier against protracted hostilities, first with Plains Indian tribes, and after the Texas Revolution, hostilities with Mexico.

Juan Crow is political terminology that was coined by journalist Roberto Lovato. It first gained popularity when he used it in an article for The Nation magazine in 2008. "Call it Juan Crow: the matrix of laws, social customs, economic institutions and symbolic systems enabling the physical and psychic isolation needed to control and exploit undocumented immigrants." Lovato utilized the term to criticize immigration enforcement laws by analogizing them to Jim Crow laws, and has since become popular among immigration activists.

The Mexican Border War, or the Border Campaign, was a series of military engagements which took place in the Mexican–American border region of North America during the Mexican Revolution. The period of the war encompassed World War I, and the German Empire attempted to have Mexico attack the United States, as well as engaging in hostilities against American forces there itself.

The Plan of San Diego was a plan drafted in San Diego, Texas, in 1915 by a group of unidentified Mexican and Tejano rebels who hoped to seize Arizona, New Mexico, California, and Texas from the United States. The plan was never attempted. It called for a general uprising in February, 1915, and the mass-killings of every non-Hispanic Caucasian male over 16 years of age. The arena included all of South Texas. Germans were excluded from the killings. The San Diego Plan collapsed immediately on discovery.

The Ojo de Agua Raid was the last important military engagement between Mexican Seditionistas and the United States Army. It took place at Ojo de Agua, Texas. As part of the Plan of San Diego, the rebels launched a raid across the Rio Grande into Texas on October 21, 1915 aimed at harassing the American outposts along the Mexican border and disrupting the local economy. After moving across the border, the Seditionistas began an assault against the United States Army Signal Corps station at Ojo de Agua. The small group of American defenders was cornered into a single building and suffered heavy casualties before reinforcements arrived driving the Seditionist force back into Mexico. The raid proved to be the tipping point in the American conflict with the Seditionistas, as its severity convinced American officials to send large numbers of American troops to the area in order to deter any further serious border raids by the Mexican force.

The Garza Revolution, or the Garza War, was an armed conflict fought in the Mexican state of Coahuila and the American state of Texas between 1891 and 1893. It began when the revolutionary Catarino Garza launched a campaign into Mexico from Texas to start an uprising against the dictator Porfirio Diaz. Because of this violation of neutrality, the United States Army became involved and assisted the Mexican Army in tracking down Garza's followers. The war was relatively minor compared to other similar conflicts in Mexican history though it has been seen as a precursor to the major Mexican Revolution from 1910 to 1920.

The Bandit War, or Bandit Wars, was a series of raids in Texas that started in 1915 and finally culminated in 1919. They were carried out by Mexican rebels from the states of Tamaulipas, Coahuila, and Chihuahua. Prior to 1914, the Carrancistas had been responsible for most attacks along the border, but in January 1915, rebels known as Seditionistas drafted the Plan of San Diego and began launching their own raids. The plan called for a race war to rid the American border states of their Anglo-American population and for the annexation of the border states to Mexico. However, the Seditionistas could never launch a full-scale invasion of the United States and so the faction resorted to conducting small raids into Texas. Much of the fighting involved the Texas Ranger Division, but the US Army also engaged in small unit actions with bands of Seditionist raiders.

The Nevill Ranch raid occurred on the night of March 25, 1918, and was the last serious attack on a Texas ranch by Mexican rebels during the Bandit War. It is not certain, but there was reason to believe that Villistas were responsible for the raid in which two people were murdered. Afterwards, the rebels withdrew to the village of Pilares, Chihuahua, in Mexican territory, under pursuit by a group of United States cavalry. A small battle was fought at Pilares on the following day, several more people were killed, and the Americans burned the village before they returned to Texas.

Indigenous peoples lived in the area now known as Texas long before Spanish explorers arrived in the area. However, once Spaniards arrived and claimed the area for Spain, a process known as mestizaje occurred, in which Spaniards and Native Americans had mestizo children who had both Spanish and indigenous blood. Texas was ruled by Spain as part of its New Spain territory from 1520, when Spaniards first arrived in Mexico in 1520, until Texas won independence from Mexico in 1836, which led to the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo (1848). In 1830, the Mexican population fell to 20 percent and in 1840 down to 10 percent. When Spanish rule in Texas ended, Mexicans in Texas numbered 5,000. In 1850 over 14,000 Texas residents had Mexican origin.

Hispanic and Latino Texans are residents of the state of Texas who are of Hispanic or Latino ancestry. As of the 2020 U.S. Census, Hispanics and Latinos of any race were 39.3% of the state's population. Moreover, the U.S Census shows that the 2010 estimated Hispanic population in Texas was 9.7 million and increased to 11.4 million in 2020 with a 2,064,657 population jump from the 2010 Latino population estimate.

The Porvenir massacre was an incident on January 28, 1918, outside the village of Porvenir, in Presidio County, Texas, in which Texas Rangers and local ranchers, with the support of U.S. Cavalry, killed 15 unarmed Mexican American boys and men. The Texas Rangers Company B had been sent to the area to stop banditry after the Brite Ranch raid. Despite having no evidence that the Porvenir villagers had been involved in recent thefts or the killings of ranchers, the Rangers separated 15 men and boys from the rest of the village and shot them on a nearby hill.

The Canales Investigation was a 1919 legislative hearing into criminal conduct of the Texas Rangers, named for Texas State Representative José Tomás (J.T.) Canales. The purpose of the hearing was to "investigate the activities and necessity for a continuance of the force." The investigations surfaced several allegations of wrongdoing, from murder to intimidation charges, with varying degrees of evidence. The committee absolved the Texas Rangers of all legal wrongdoing while acknowledging a track record of abuse, and commended the adjutant general of the Texas Rangers. Nonetheless, the investigation sparked internal reform of the Texas Rangers aimed to increase professionalism and accountability.

José Tomás Canales was an American businessman, lawyer, and politician based in Texas. He served five terms in the State House, where he was the only Mexican-American representative at the time. He is best known for his work on behalf of Mexican-Americans and Tejanos in Texas, defending civil rights of Latin Americans and other minorities.

Monica Muñoz Martinez is a scholar of Mexican-American history current serving as an Associate Professor of History at the University of Texas at Austin. Martinez was previously the Stanley J. Bernstein Assistant Professor of American Studies and Ethnic Studies at Brown University and an Andrew Carnegie Fellow. Her research has been supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation, and the Texas State Historical Association. She has received praise for her work on several public history projects and her first book, The Injustice Never Leaves You: Anti-Mexican Violence in Texas was published in 2018 and received numerous awards. In 2021 she received a "Genius Grant" from the MacArthur Foundation.