Related Research Articles

The Council of Chalcedon was the fourth ecumenical council of the Christian Church. It was convoked by the Roman emperor Marcian. The council convened in the city of Chalcedon, Bithynia from 8 October to 1 November 451. The council was attended by over 520 bishops or their representatives, making it the largest and best-documented of the first seven ecumenical councils. The principal purpose of the council was to re-assert the teachings of the ecumenical Council of Ephesus against the teachings of Eutyches and Nestorius. Such doctrines viewed Christ's divine and human natures as separate (Nestorianism) or viewed Christ as solely divine (monophysitism).

Ephesus was a city in Ancient Greece on the coast of Ionia, 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) southwest of present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in the 10th century BC on the site of Apasa, the former Arzawan capital, by Attic and Ionian Greek colonists. During the Classical Greek era, it was one of twelve cities that were members of the Ionian League. The city came under the control of the Roman Republic in 129 BC.

Western Christianity is one of two subdivisions of Christianity. Western Christianity is composed of the Latin Church and Western Protestantism, together with their offshoots such as the Old Catholic Church, Independent Catholicism and Restorationism.

Eastern Christianity comprises Christian traditions and church families that originally developed during classical and late antiquity in the Eastern Mediterranean region or locations further east, south or north. The term does not describe a single communion or religious denomination. Eastern Christianity is a category distinguished from Western Christianity, which is composed of those Christian traditions and churches that originally developed further west.

An apostolic see is an episcopal see whose foundation is attributed to one or more of the apostles of Jesus or to one of their close associates. In Catholicism, the phrase "The Apostolic See" when capitalized refers specifically to the See of Rome.

Banditry is a type of organized crime committed by outlaws typically involving the threat or use of violence. A person who engages in banditry is known as a bandit and primarily commits crimes such as extortion, robbery, kidnapping, and murder, either as an individual or in groups. Banditry is a vague concept of criminality and in modern usage can be synonymous with gangsterism, brigandage, marauding, terrorism, piracy, and thievery.

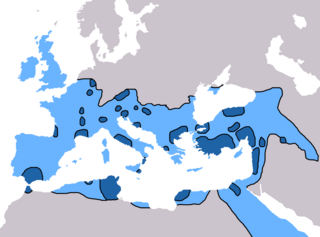

Late antiquity is sometimes defined as spanning from the end of classical antiquity to the local start of the Middle Ages, from around the late 3rd century up to the 7th or 8th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin depending on location. The popularisation of this periodization in English has generally been credited to historian Peter Brown, who proposed a period between 150 and 750 AD. The Oxford Centre for Late Antiquity defines it as "the period between approximately 250 and 750 AD". Precise boundaries for the period are a continuing matter of debate. In the West, its end was earlier, with the start of the Early Middle Ages typically placed in the 6th century, or even earlier on the edges of the Western Roman Empire.

In Christianity, a martyr is a person who was killed for their testimony for Jesus or faith in Jesus. In the years of the early church, stories depict this often occurring through death by sawing, stoning, crucifixion, burning at the stake, or other forms of torture and capital punishment. The word martyr comes from the Koine word μάρτυς, mártys, which means "witness" or "testimony".

Eusebius of Dorylaeum was the 5th-century bishop of Dorylaeum, who spoke out against dissident teachings, especially those of Nestorius and Eutyches, during the period of Christological controversy. After succeeding in having them expelled from their positions, Eusebius was himself deposed and only reinstated two years later, after which the doctrine in dispute was more precisely defined.

Pentarchy was a model of Church organization formulated in the laws of Emperor Justinian I of the Roman Empire. In this model, the Christian Church is governed by the heads (patriarchs) of the five major episcopal sees of the Roman Empire: Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem.

The Byzantine Greeks were the Greek-speaking Eastern Romans throughout Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. They were the main inhabitants of the lands of the Byzantine Empire, of Constantinople and Asia Minor, the Greek islands, Cyprus, and portions of the southern Balkans, and formed large minorities, or pluralities, in the coastal urban centres of the Levant and northern Egypt. Throughout their history, the Byzantine Greeks self-identified as Romans, but are referred to as "Byzantine Greeks" in modern historiography. Latin speakers identified them simply as Greeks or with the term Romaei.

Oriental studies is the academic field that studies Near Eastern and Far Eastern societies and cultures, languages, peoples, history and archaeology. In recent years, the subject has often been turned into the newer terms of Middle Eastern studies and Asian studies. Traditional Oriental studies in Europe is today generally focused on the discipline of Islamic studies; the study of China, especially traditional China, is often called Sinology. The study of East Asia in general, especially in the United States, is often called East Asian studies.

In the history of Christianity, the first seven ecumenical councils include the following: the First Council of Nicaea in 325, the First Council of Constantinople in 381, the Council of Ephesus in 431, the Council of Chalcedon in 451, the Second Council of Constantinople in 553, the Third Council of Constantinople from 680 to 681 and finally, the Second Council of Nicaea in 787. All of the seven councils were convened in what is now the country of Turkey.

In the 5th century in Christianity, there were many developments which led to further fracturing of the State church of the Roman Empire. Emperor Theodosius II called two synods in Ephesus, one in 431 and one in 449, that addressed the teachings of Patriarch of Constantinople Nestorius and similar teachings. Nestorius had taught that Christ's divine and human nature were distinct persons, and hence Mary was the mother of Christ but not the mother of God. The Council rejected Nestorius' view causing many churches, centered on the School of Edessa, to a Nestorian break with the imperial church. Persecuted within the Roman Empire, many Nestorians fled to Persia and joined the Sassanid Church thereby making it a center of Nestorianism. By the end of the 5th century, the global Christian population was estimated at 10-11 million. In 451 the Council of Chalcedon was held to clarify the issue further. The council ultimately stated that Christ's divine and human nature were separate but both part of a single entity, a viewpoint rejected by many churches who called themselves miaphysites. The resulting schism created a communion of churches, including the Armenian, Syrian, and Egyptian churches, that is today known as Oriental Orthodoxy. In spite of these schisms, however, the imperial church still came to represent the majority of Christians within the Roman Empire.

Christianity in the 11th century is marked primarily by the Great Schism of the Church, which formally divided the State church of the Roman Empire into Eastern (Greek) and Western (Latin) branches.

Christianity in late antiquity traces Christianity during the Christian Roman Empire — the period from the rise of Christianity under Emperor Constantine, until the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The end-date of this period varies because the transition to the sub-Roman period occurred gradually and at different times in different areas. One may generally date late ancient Christianity as lasting to the late 6th century and the re-conquests under Justinian of the Byzantine Empire, though a more traditional end-date is 476, the year in which Odoacer deposed Romulus Augustus, traditionally considered the last western emperor.

In the year before the First Council of Constantinople in 381, Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire when Theodosius I, emperor of the East, Gratian, emperor of the West, and Gratian's junior co-ruler Valentinian II issued the Edict of Thessalonica in 380, which recognized the catholic orthodoxy of Nicene Christians as the Roman Empire's state religion. Historians refer to the Nicene church associated with emperors in a variety of ways: as the catholic church, the orthodox church, the imperial church, the Roman church, or the Byzantine church, although some of those terms are also used for wider communions extending outside the Roman Empire. The Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodoxy, and the Catholic Church all claim to stand in continuity from the Nicene church to which Theodosius granted recognition.

Sectarian violence among Christians is a recurring phenomenon, in which Christians engage in a form of communal violence known as sectarian violence. This form of violence can frequently be attributed to differences of religious beliefs between sects of Christianity (sectarianism). Sectarian violence among Christians was common, especially during late antiquity, and the years surrounding the Protestant Reformation, in which the German monk Martin Luther disputed some of the Catholic Church's practices; particularly the doctrine of Indulgences, and it was crucial in the formation of a new sect of Christianity known as Protestantism. During the latter half of the Renaissance was when sectarianism related violence was most common among Christians. Conflicts like the European wars of religion or Dutch Revolt ravaged Western Europe. In France there were the French Wars of Religion and in the United Kingdom anti-Catholic hate was heightened by the Gunpowder Plot of 1605. And while sectarian violence may seem like an archaic footnote today, sectarian violence among Christians still persists in the modern world with groups such as the Ku Klux Klan perpetuating violence among Catholics.

Bulla Felix was a legendary Italian bandit leader active around 205–207 AD, during the reign of the Roman emperor Septimius Severus. He gathered a band of over 600 men, among them runaway slaves and imperial freedmen, and eluded capture for more than two years despite pursuit by a force of Roman soldiers under the command of the emperor himself.

Dioclea was a town of ancient Phrygia, inhabited during Roman and Byzantine times.

References

- ↑ "Larceny". Webster's Online Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2007-10-12. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- ↑ Grunewald, Thomas (2004). Bandits in the Roman Empire: Myth and Reality. Taylor & Francis. p. 40. ISBN 9780415327442.

- ↑ Grunewald, Bandits in the Roman Empire, pp. 10ff., 58, et passim.

- ↑ Michael Gaddis, There Is No Crime for Those Who Have Christ: Religious Violence in the Christian Roman Empire (University of California Press, 2005), pp. 20, 151.

- ↑ Giardina, Andrea, ed. (1993). The Romans. University of Chicago Press. p. 305. ISBN 9780226290492.

- ↑ Gaddis, Religious Violence in the Christian Roman Empire, p. 75.

- ↑ John-Peter Pham, Heirs of the Fisherman : Behind the Scenes of Papal Death and Succession (Oxford University Press, 2004), p. 296.

- ↑ Russell, Frederick H. (1977). The Just War in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press. p. 5. ISBN 9780521292764.