Related Research Articles

In economics and finance, arbitrage is the practice of taking advantage of a difference in prices in two or more markets; striking a combination of matching deals to capitalise on the difference, the profit being the difference between the market prices at which the unit is traded. When used by academics, an arbitrage is a transaction that involves no negative cash flow at any probabilistic or temporal state and a positive cash flow in at least one state; in simple terms, it is the possibility of a risk-free profit after transaction costs. For example, an arbitrage opportunity is present when there is the possibility to instantaneously buy something for a low price and sell it for a higher price.

In finance, a derivative is a contract that derives its value from the performance of an underlying entity. This underlying entity can be an asset, index, or interest rate, and is often simply called the underlying. Derivatives can be used for a number of purposes, including insuring against price movements (hedging), increasing exposure to price movements for speculation, or getting access to otherwise hard-to-trade assets or markets.

A monopoly, as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situation where a specific person or enterprise is the only supplier of a particular thing. This contrasts with a monopsony which relates to a single entity's control of a market to purchase a good or service, and with oligopoly and duopoly which consists of a few sellers dominating a market. Monopolies are thus characterised by a lack of economic competition to produce the good or service, a lack of viable substitute goods, and the possibility of a high monopoly price well above the seller's marginal cost that leads to a high monopoly profit. The verb monopolise or monopolize refers to the process by which a company gains the ability to raise prices or exclude competitors. In economics, a monopoly is a single seller. In law, a monopoly is a business entity that has significant market power, that is, the power to charge overly high prices, which is associated with a decrease in social surplus. Although monopolies may be big businesses, size is not a characteristic of a monopoly. A small business may still have the power to raise prices in a small industry.

A commodity market is a market that trades in the primary economic sector rather than manufactured products, such as cocoa, fruit and sugar. Hard commodities are mined, such as gold and oil. Futures contracts are the oldest way of investing in commodities. Commodity markets can include physical trading and derivatives trading using spot prices, forwards, futures, and options on futures. Farmers have used a simple form of derivative trading in the commodity market for centuries for price risk management.

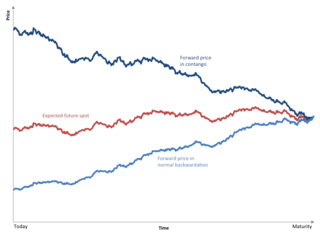

Contango is a situation where the futures price of a commodity is higher than the expected spot price of the contract at maturity. In a contango situation, arbitrageurs or speculators are "willing to pay more [now] for a commodity [to be received] at some point in the future than the actual expected price of the commodity [at that future point]. This may be due to people's desire to pay a premium to have the commodity in the future rather than paying the costs of storage and carry costs of buying the commodity today." On the other side of the trade, hedgers are happy to sell futures contracts and accept the higher-than-expected returns. A contango market is also known as a normal market, or carrying-cost market.

Purchasing power parity (PPP) is a measurement of the price of specific goods in different countries and is used to compare the absolute purchasing power of the countries' currencies. PPP is effectively the ratio of the price of a basket of goods at one location divided by the price of the basket of goods at a different location. The PPP inflation and exchange rate may differ from the market exchange rate because of tariffs, and other transaction costs.

Price discrimination is a microeconomic pricing strategy where identical or largely similar goods or services are sold at different prices by the same provider in different market segments. Price discrimination is distinguished from product differentiation by the more substantial difference in production cost for the differently priced products involved in the latter strategy. Price differentiation essentially relies on the variation in the customers' willingness to pay and in the elasticity of their demand. For price discrimination to succeed, a firm must have market power, such as a dominant market share, product uniqueness, sole pricing power, etc. All prices under price discrimination are higher than the equilibrium price in a perfectly competitive market. However, some prices under price discrimination may be lower than the price charged by a single-price monopolist. Price discrimination is utilised by the monopolist to recapture some deadweight loss. This Pricing strategy enables firms to capture additional consumer surplus and maximize their profits while benefiting some consumers at lower prices. Price discrimination can take many forms and is prevalent in many industries, from education and telecommunications to healthcare.

A price is the quantity of payment or compensation expected, required, or given by one party to another in return for goods or services. In some situations, the price of production has a different name. If the product is a "good" in the commercial exchange, the payment for this product will likely be called its "price". However, if the product is "service", there will be other possible names for this product's name. For example, the graph on the bottom will show some situations A good's price is influenced by production costs, supply of the desired item, and demand for the product. A price may be determined by a monopolist or may be imposed on the firm by market conditions.

A grey market or dark market is the trade of a commodity through distribution channels that are not authorized by the original manufacturer or trade mark proprietor. Grey market products are products traded outside the authorized manufacturer's channel.

In finance, a futures contract is a standardized legal contract to buy or sell something at a predetermined price for delivery at a specified time in the future, between parties not yet known to each other. The asset transacted is usually a commodity or financial instrument. The predetermined price of the contract is known as the forward price. The specified time in the future when delivery and payment occur is known as the delivery date. Because it derives its value from the value of the underlying asset, a futures contract is a derivative.

A hedge is an investment position intended to offset potential losses or gains that may be incurred by a companion investment. A hedge can be constructed from many types of financial instruments, including stocks, exchange-traded funds, insurance, forward contracts, swaps, options, gambles, many types of over-the-counter and derivative products, and futures contracts.

An exchange-traded fund (ETF) is a type of investment fund and exchange-traded product, i.e. they are traded on stock exchanges. ETFs are similar in many ways to mutual funds, except that ETFs are bought and sold from other owners throughout the day on stock exchanges whereas mutual funds are bought and sold from the issuer based on their price at day's end. ETFs can hold assets such as stocks, bonds, currencies, futures contracts, and/or commodities such as gold bars, and generally operates with an arbitrage mechanism designed to keep it trading close to its net asset value, although deviations can occasionally occur. Most ETFs are index funds: that is, they hold the same securities in the same proportions as a certain stock market index or bond market index. The most popular ETFs in the U.S. replicate the S&P 500, the total market index, the NASDAQ-100 index, the price of gold, the "growth" stocks in the Russell 1000 Index, or the index of the largest technology companies. The list of assets that each ETF owns, as well as their weightings, is posted on the website of the issuer daily, or quarterly in the case of active non-transparent ETFs. The largest ETFs have annual fees of 0.03% of the amount invested, or even lower, although specialty ETFs can have annual fees of 1% or more of the amount invested. These fees are paid to the ETF issuer out of dividends received from the underlying holdings or from selling assets.

Program trading is a type of trading in securities, usually consisting of baskets of fifteen stocks or more that are executed by a computer program simultaneously based on predetermined conditions. Program trading is often used by hedge funds and other institutional investors pursuing index arbitrage or other arbitrage strategies. There are essentially two reasons to use program trading, either because of the desire to trade many stocks simultaneously, or alternatively to arbitrage temporary price discrepancies between related financial instruments, such as between an index and its constituent parts.

A parallel import is a non-counterfeit product imported from another country without the permission of the intellectual property owner. Parallel imports are often referred to as grey product and are implicated in issues of international trade, and intellectual property.

The law of the value of commodities, known simply as the law of value, is a central concept in Karl Marx's critique of political economy first expounded in his polemic The Poverty of Philosophy (1847) against Pierre-Joseph Proudhon with reference to David Ricardo's economics. Most generally, it refers to a regulative principle of the economic exchange of the products of human work, namely that the relative exchange-values of those products in trade, usually expressed by money-prices, are proportional to the average amounts of human labor-time which are currently socially necessary to produce them within the capitalist mode of production.

Market structure, in economics, depicts how firms are differentiated and categorised based on the types of goods they sell (homogeneous/heterogeneous) and how their operations are affected by external factors and elements. Market structure makes it easier to understand the characteristics of diverse markets.

Algorithmic trading is a method of executing orders using automated pre-programmed trading instructions accounting for variables such as time, price, and volume. This type of trading attempts to leverage the speed and computational resources of computers relative to human traders. In the twenty-first century, algorithmic trading has been gaining traction with both retail and institutional traders. It is widely used by investment banks, pension funds, mutual funds, and hedge funds that may need to spread out the execution of a larger order or perform trades too fast for human traders to react to. A study in 2019 showed that around 92% of trading in the Forex market was performed by trading algorithms rather than humans.

In economics, a market is a composition of systems, institutions, procedures, social relations or infrastructures whereby parties engage in exchange. While parties may exchange goods and services by barter, most markets rely on sellers offering their goods or services to buyers in exchange for money. It can be said that a market is the process by which the prices of goods and services are established. Markets facilitate trade and enable the distribution and allocation of resources in a society. Markets allow any tradeable item to be evaluated and priced. A market emerges more or less spontaneously or may be constructed deliberately by human interaction in order to enable the exchange of rights of services and goods. Markets generally supplant gift economies and are often held in place through rules and customs, such as a booth fee, competitive pricing, and source of goods for sale.

In economics and finance, the price discovery process is the process of determining the price of an asset in the marketplace through the interactions of buyers and sellers.

This glossary of economics is a list of definitions of terms and concepts used in economics, its sub-disciplines, and related fields.

References

- ↑ Feenstra, Robert. International .There is a basic principle in economics called "the law of one price". This states that identical goods should have identical prices. For example, an ounce of silver should cost the same in the New York and Paris, otherwise silver would flow from one city to the other. Of course, this law does not always hold in practice, unless there are competitive markets, no transaction costs and no trade barriers...

- ↑ "Law of one price Definition". NASDAQ . Retrieved 3 December 2015.

An economic rule stating that a given security must have the same price no matter how the security is created. If the payoff of a security can be synthetically created by a package of other securities, the implication is that the price of the package and the price of the security whose payoff it replicates must be equal. If it is unequal, an arbitrage opportunity would present itself.

- ↑ "law of one price". Cambridge University Press 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

ECONOMICS[:] [T]he principle that in a perfect financial market goods would have the same price everywhere[.]

- ↑ "Law of One Price Definition". Investopedia . Retrieved 3 December 2015.

The theory that the price of a given security, commodity or asset will have the same price when exchange rates are taken into consideration. The law of one price is another way of stating the concept of purchasing power parity[...]The law of one price exists due to arbitrage opportunities. If the price of a security, commodity or asset is different in two different markets, then an arbitrageur will purchase the asset in the cheaper market and sell it where prices are higher[...]When the purchasing power parity doesn't hold, arbitrage profits will persist until the price converges across markets.

- 1 2 "What is Law of One Price?". WebFinance, Inc. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

An economic rule which states that in an efficient market, a security must have a single price, no matter how that security is created. For example, if an option can be created using two different sets of underlying securities, then the total price for each would be the same or else an arbitrage opportunity would exist.

- ↑ Rashid, Salim (Spring 2007). "The "Law" of One Price: Implausible, Yet Consequential". Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics . 10 (1): 79. doi:10.1007/s12113-007-9001-7. S2CID 17745635.

The law of one price (hereafter LoP) is one of the most basic laws of economics and yet it is a law observed in the breach. That a given commodity can have only one price, except for the briefest of [disequilibrium] transitions, seems to be almost an axiom...

- ↑ Mankiw, N. G. (2011). Principles of Economics (6th ed.). Mason, OH: South-Western Cengage Learning. Page 686.

- 1 2 3 Karl Gunnar Persson (10 February 2008). "Definitions and Explanation of the Law of One Price". eh.net. Economic History Services. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ↑ Burdett, Kenneth, and Kenneth Judd (1983), 'Equilibrium price dispersion'. Econometrica 51 (4), pp. 955-69.

- ↑ Taylor, Alan; Feenstra, Robert (2012). International Macroeconomics. p. 65.

- ↑ Carlos Góes; Troy Matheson (2015). "Domestic Market Integration and the Law of One Price in Brazil". IMF Working Paper, Western Hemisphere Department. International Monetary Fund (Working Paper No. 15/213). Retrieved 3 December 2015.

This paper presents the first assessment domestic market integration in Brazil using the law of one price. The law of one price is tested using two panel unit root methodologies and a unique data set comprising price indices for 51 products across 11 metro-areas. We find that the law of one price holds for most tradable products and, not surprisingly, non-tradable products are found to be less likely to satisfy the law of one price. While these findings are consistent with evidence found for other countries, price convergence occurs very slowly in Brazil, suggesting relatively limited domestic market integration.

- ↑ Steil, Benn; Dinah Walker. "The New Geo-Graphics iPad Mini Index Should Calm Talk of Currency Wars". Council on Foreign Relations . Retrieved 3 December 2015.

...We've created our own index which better meets the condition that the product can flow quickly and cheaply across borders: meet the new Geo-Graphics iPad mini Index[...]The iPad mini is a global product that travels by plane in a coat pocket, unlike a burger, and its manufacturer, Apple, is highly attuned to shifting currency values[...]"We made some pricing adjustments due to changes in foreign exchange rates," Apple spokesman Takashi Tabayashi told Bloomberg News after Apple raised Japanese iPad prices 15% in May, offsetting the early effect of Abenomics on the yen[...]As this week's Geo-Graphic shows, there are no major violations of the law of one price in the global market for iPad minis – unlike the market for Big Macs.[...]This is particularly the case after stripping out Value-Added Tax distortions.[...](Sales tax in many countries, like the United States, is not included in the sales price Apple advertises, but VAT is included in such prices for VAT-levying countries. VAT is also at least partly refundable for foreigners exporting the product.)...

- ↑ Prasodjo, Darmawan. "Law of One Price defeats oil subsidy". The Jakarta Post . Retrieved 3 December 2015.

...These fuel subsidies place a serious burden on the government budget and it is sad to see its good intentions thwarted to such an extent. Although the fight against fuel smuggling may be noble, an economics theory makes it look like a losing battle: the Law of One Price says you can't stop it[...]The Law of One Price says the same gasoline should have the same price anywhere (with transportation costs factored in) and that particular price is set by sellers flocking to the highest price. In an efficient market, this activity leads to equilibrium as supply and demand constantly respond to ongoing conditions.[...]But smugglers hijack these market principles while stealing the fuel. They steal subsidized oil and flock to a full-price market as the price differential and market boundaries create an opportunity...

- ↑ Lamont, Owen A; Thaler, Richard H (November 2003). "Anomalies: The Law of One Price in Financial Markets". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 17 (4): 191–202. doi: 10.1257/089533003772034952 .

- Fan, C. Simon; Wei, Xiangdong (November 2006). "The Law of One Price: Evidence from the Transitional Economy of China". Review of Economics and Statistics. 88 (4): 682–697. doi:10.1162/rest.88.4.682. S2CID 16524994.