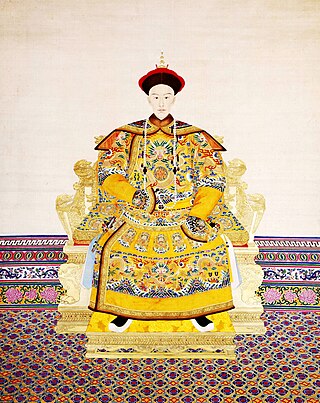

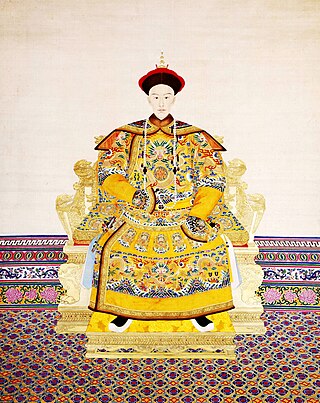

The Qing dynasty, officially the Great Qing, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last imperial dynasty in Chinese history. The dynasty, proclaimed in Shenyang in 1636, seized control of Beijing in 1644, which is considered the start of the dynasty's rule. The dynasty lasted until 1912, when it was overthrown in the Xinhai Revolution. In Chinese historiography, the Qing dynasty was preceded by the Ming dynasty and succeeded by the Republic of China. The multi-ethnic Qing dynasty assembled the territorial base for modern China. It was the largest imperial dynasty in the history of China and in 1790 the fourth-largest empire in world history in terms of territorial size. With over 426 million citizens in 1907, it was the most populous country in the world at the time.

Manchuria is a term that refers to a region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China, and historically parts of the modern-day Russian Far East, often referred to as Outer Manchuria. Its definition may refer to varying geographical extents as follows: the Chinese provinces of Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning but broadly also including the eastern Inner Mongolian prefectures of Hulunbuir, Hinggan, Tongliao, and Chifeng, collectively known as Northeast China; the aforementioned regions plus the homelands of ancient Jurchen and their descendant Manchus ceded to the Russian Empire by the Manchu-led Qing dynasty during the Amur Annexation of 1858–1860, which include present-day Primorsky Krai, the Jewish Autonomous Oblast, the southern part of Khabarovsk Krai, the eastern edge of Zabaykalsky Krai, and Amur Oblast, collectively known as the Outer Manchuria or Russian Manchuria.

China proper, also called Inner China are terms used primarily in the West in reference to the traditional "core" regions of China. The term was first used by Westerners during the Manchu-led Qing dynasty to describe the distinction between the historical "Han lands" (漢地)—i.e. regions long dominated by the majority Han population—and the "frontier" regions of China where more non-Han ethnic groups and new foreign immigrants reside, sometimes known as "Outer China". There is no fixed extent for China proper, as many administrative, cultural, and linguistic shifts have occurred in Chinese history. One definition refers to the original area of Chinese civilization, the Central Plain ; another to the Eighteen Provinces of the Qing dynasty. There was no direct translation for "China proper" in the Chinese language at the time due to differences in terminology used by the Qing to refer to the regions. Even to today, the expression is controversial among scholars, particularly in mainland China, due to issues pertaining to contemporary territorial claim and ethnic politics.

The Manchus are a Tungusic East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized ethnic minority in China and the people from whom Manchuria derives its name. The Later Jin (1616–1636) and Qing (1636–1912) dynasties of China were established and ruled by the Manchus, who are descended from the Jurchen people who earlier established the Jin dynasty (1115–1234) in northern China. Manchus form the largest branch of the Tungusic peoples and are distributed throughout China, forming the fourth largest ethnic group in the country. They can be found in 31 Chinese provincial regions. Among them, Liaoning has the largest population and Hebei, Heilongjiang, Jilin, Inner Mongolia and Beijing have over 100,000 Manchu residents. About half of the population live in Liaoning and one-fifth in Hebei. There are a number of Manchu autonomous counties in China, such as Xinbin, Xiuyan, Qinglong, Fengning, Yitong, Qingyuan, Weichang, Kuancheng, Benxi, Kuandian, Huanren, Fengcheng, Beizhen and over 300 Manchu towns and townships. Manchus are the largest minority group in China without an autonomous region.

Jurchen is a term used to collectively describe a number of East Asian Tungusic-speaking people. They lived in northeastern China, also known as Manchuria, before the 18th century. The Jurchens were renamed Manchus in 1635 by Hong Taiji. Different Jurchen groups lived as hunter-gatherers, pastoralist semi-nomads, or sedentary agriculturists. Generally lacking a central authority, and having little communication with each other, many Jurchen groups fell under the influence of neighbouring dynasties, their chiefs paying tribute and holding nominal posts as effectively hereditary commanders of border guards.

Sinocentrism refers to the worldview that China is the cultural, political, or economic center of the world.

Mongolia under Qing rule was the rule of the Manchu-led Qing dynasty of China over the Mongolian Plateau, including the four Outer Mongolian aimags and the six Inner Mongolian aimags from the 17th century to the end of the dynasty. The term "Mongolia" is used here in the broader historical sense, and includes an area much larger than the modern-day state of Mongolia. By the early 1630s Ligdan Khan saw much of his power weakened due to the disunity of the Mongol tribes. He was subsequently defeated by the Later Jin dynasty and died soon afterwards. His son Ejei handed the Yuan imperial seal over to Hong Taiji in 1635, thus ending the rule of the Northern Yuan dynasty in Inner Mongolia. However, the Khalkha Mongols in Outer Mongolia continued to rule until they were overrun by the Dzungar Khanate in 1690, and they submitted to the Qing dynasty in 1691.

De-Sinicization is a process of eliminating or reducing Han Chinese cultural elements, identity, or consciousness from a society or nation. In modern contexts, it is often contrasted with the assimilation process of Sinicization.

A conquest dynasty in the history of China refers to a Chinese dynasty established by non-Han ethnicities which ruled parts or all of China proper, the traditional heartland of the Han people, and whose rulers may or may not have fully assimilated into the dominant Han culture.

Ping-ti Ho or Bingdi He, who also wrote under the name P.T. Ho, was a Chinese-American historian. He wrote widely on China's history, including works on demography, plant history, ancient archaeology, and contemporary events. He taught at University of Chicago for most of his career, and was president of the Association for Asian Studies in 1975, the first scholar of East Asian descent to have that honor.

The Imperial Clan Court or Court of the Imperial Clan was an institution responsible for all matters pertaining to the imperial family under the Ming and Qing dynasties of imperial China. This institution also existed under the Nguyễn dynasty of Vietnam where it managed matters pertaining to the Nguyễn Phúc clan.

The history of the Qing dynasty began with the proclamation of the Qing dynasty by the Manchu chieftain Hong Taiji in 1636, but the year 1644 is generally considered the start of the dynasty's rule in China. The dynasty lasted until 1912, when Puyi abdicated the throne in response to the 1911 Revolution. The final imperial dynasty of China, the Qing dynasty reached heights of power unlike any of the Chinese dynasties which preceded it, engaging in large-scale territorial expansion which ended with embarrassing defeat and humiliation to the foreign powers whom they believe to be inferior to them. The Qing dynasty's inability to successfully counter Western and Japanese imperialism ultimately led to its downfall, and the instability which emerged in China during the final years of the dynasty ultimately paved the way for the Warlord Era.

Shamanism was the dominant religion of the Jurchen people of northeast Asia and of their descendants, the Manchu people. As early as the Jin dynasty (1115–1234), the Jurchens conducted shamanic ceremonies at shrines called tangse. There were two kinds of shamans: those who entered in a trance and let themselves be possessed by the spirits, and those who conducted regular sacrifices to heaven, to a clan's ancestors, or to the clan's protective spirits.

The New Qing History is a historiographical school that gained prominence in the United States in the mid-1990s by offering a major revision of history of the Manchu-led Qing dynasty of China.

Evelyn Sakakida Rawski is an American scholar of Chinese and Inner Asian history. She is currently a Distinguished University Professor in the Department of History of the University of Pittsburgh. She was born in Honolulu, Hawaii, United States of Japanese-American ancestry. She served as president of the Association for Asian Studies in 1995–1996.

The Qing dynasty was an imperial Chinese dynasty ruled by the Aisin Gioro clan of Manchu ethnicity. Officially known as the Great Qing, the dynastic empire was also widely known in English as China and the Chinese Empire both during its existence, especially internationally, and after the fall of the dynasty.

The Qing dynasty in Inner Asia was the expansion of the Qing dynasty's realm in Inner Asia in the 17th and the 18th century AD, including both Inner Mongolia and Outer Mongolia, both Manchuria and Outer Manchuria, Tibet, Qinghai and Xinjiang.

The Sinicization of the Manchus is the process in which the Manchu people became assimilated into the Han-dominated Chinese society. It had occurred most prominently during the Qing dynasty when attempts were made by the new Manchu rulers of China to assimilate themselves and their people with the Han under the new dynasty to increase its legitimacy.

The debate on the "Chineseness" of the Yuan and Qing dynasties is concerned with whether the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) and the Manchu-led Qing dynasty (1644–1912) can be considered "Chinese dynasties", and whether they were representative of "China" during the respective historical periods. The debate, albeit historiographical in nature, has political implications. Mainstream academia and successive governments of China, including the imperial governments of the Yuan and Qing dynasties, have maintained the view that they were "Chinese" and representative of "China". In short, the cause of the controversy stems from the dispute in interpreting the relationship between the two concepts of "Han Chinese" and "China", because although the Chinese government recognizes 56 ethnic groups in China and the Han have a more open view of the Yuan and Qing dynasties since Liang Qichao and other royalist reformers supported the Qing dynasty, the Han are China's main ethnic group. This means that there are many opinions that equate Han Chinese people with China and lead to criticism of the legitimacy of these two dynasties.

The History of Qing is an unpublished official history of the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) sponsored by the government of the People's Republic of China (PRC) between 2002 and 2023. Since the abolition of the Qing in the 1911 Revolution and the establishment of the Republic of China (ROC), there have been several concerted attempts to write an official Qing history. These are informed by the previous long-standing tradition of each Chinese dynasty writing the history of its predecessor. An unfinished Republican-era manuscript had been assembled during the 1920s, but the effort that began in 2002 has since dwarfed every comparable effort in both length and organizational scale. The project has involved the work of hundreds of scholars and specialists under the supervision of the National Qing History Compilation Committee, chaired since its founding by leading historian Dai Yi.