The Pas-de-Calais is a department in northern France named after the French designation of the Strait of Dover, which it borders. It has the most communes of all the departments of France, 890, and is the 8th most populous. It had a population of 1,465,278 in 2019. The Calais Passage connects to the Port of Calais on the English Channel. The Pas-de-Calais borders the departments of Nord and Somme and is connected to the English county of Kent via the Channel Tunnel.

The Strait of Dover or Dover Strait, is the strait at the narrowest part of the English Channel, marking the boundary between the Channel and the North Sea, and separating Great Britain from continental Europe. The shortest distance across the strait, at approximately 20 miles, is from the South Foreland, northeast of Dover in the English county of Kent, to Cap Gris Nez, a cape near to Calais in the French département of Pas-de-Calais. Between these points lies the most popular route for cross-channel swimmers. The entire strait is within the territorial waters of France and the United Kingdom, but a right of transit passage under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea allows vessels of other nations to move freely through the strait.

Guînes is a commune in the northern French department of Pas-de-Calais. Historically it was spelt Guisnes.

Le Parcq is a commune in the Pas-de-Calais department in the Hauts-de-France region of France.

Saint-Pol-sur-Ternoise is a commune in the Pas-de-Calais department in northern France. It is the seat of the canton of Saint-Pol-sur-Ternoise. The population of the town is 4,870 (2020).

The Opal Coast is a coastal region in northern France on the English Channel, popular with tourists.

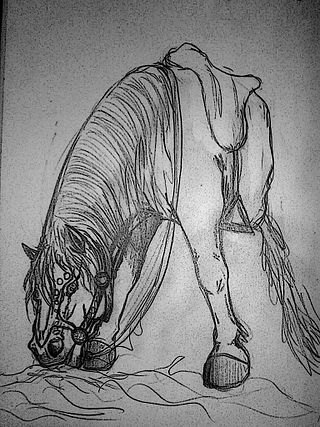

The Boulonnais, also known as the "White Marble Horse", is a draft horse breed. It is known for its large but elegant appearance and is usually gray, although chestnut and black are also allowed by the French breed registry. Originally there were several sub-types, but they were crossbred until only one is seen today. The breed's origins trace to a period before the Crusades and, during the 17th century, Spanish Barb, Arabian, and Andalusian blood were added to create the modern type.

French folklore encompasses the fables, folklore, fairy tales and legends of the French people.

The Trait du Nord, previously also known as Ardennais du Nord or Ardennais de type Nord, is a breed of heavy draft horse developed and bred in the area of Hainaut in western Belgium and in northeastern France. Originally considered a subtype of the Ardennes, it was recognized as an individual breed with the opening of a studbook in 1903. Developed in the fertile Flemish grasslands, it was bred for size and pulling power for agricultural work. By 1855, the horses bred near Hainaut were considered by some veterinarians to be superior to other Flemish draft breeds. The Trait du Nord was used extensively in mining from the late 19th century through 1920, with lesser use continuing through the 1960s.

Pernes is a commune in the Pas-de-Calais department in the Hauts-de-France region of France.

The river Ternoise is one of the small chalk streams that flow from the plateau of the southern Boulonnais and Picardy, via the Canche, into the English Channel. The basin of the Ternoise extends to 342 square kilometres (132 sq mi) and lies in the southern end of the département of Pas-de-Calais. It is one of the rivers of the Seven Valleys tourist area and gives its name to the Ternois area.

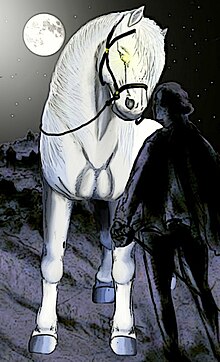

The Cheval Mallet describes a fabulous and evil horse mentioned in folklore around the French Vendée, Poitou, and more frequently in the Pays de Retz, near Lac de Grand Lieu. It was supposed to appear at night or in the middle of the night as a beautiful white or black horse, saddled and bridled, and tempt travelers exhausted by a long journey. Several legends about the unwary who rode this horse, and never returned unless you have them on the price of travel or protection spell as a medal of St. Benedict. A feast was also known as horse Merlette, Merlet or Mallet in the town of Saint-Lumine-de-Coutais, it had a military function, cathartic celebration of renewal or carnival, and featured several actors around one oak, one disguised as a horse. It was opposed by the ecclesiastical authorities and banned in 1791.

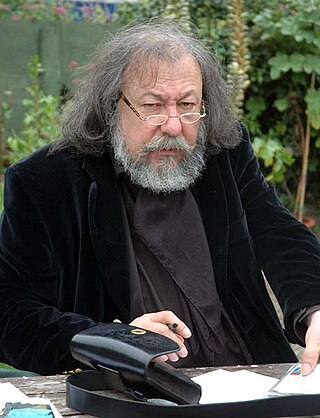

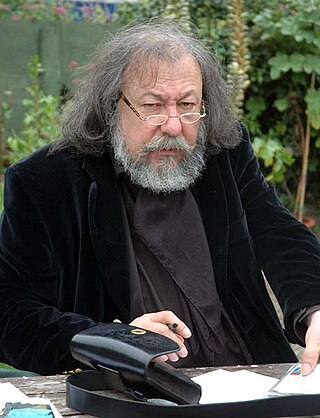

Pierre Dubois, is a French specialist in enchantement. He is an author, Franco-Belgian comics scriptwriter, storyteller and lecturer on fairies and little people in France. Fascinated at a young age with fairy tales and Fairytale fantasy, he became an illustrator after studying Fine Arts for a short period. For over 30 years, he has integrated local legends and folklore into radio and television shows. He is the inventor of elficology (elficologie) as a name for the study of the "little people", originally as a joke. His first comic book was published in 1986. Since then he has produced one annually and made regular appearances on television and at conferences relating to fairy tales, dreams and legends related to fairies.

The Cheval Gauvin is a legendary evil horse of Franche-Comté, France and the Jura Mountains in Switzerland. It is said to wander along watercourses, through forests and graveyards, and to attempt to kill those who ride it, either by drowning them or throwing them into an abyss.

The Henson Horse, or Cheval de Henson, is a modern horse breed from northeast France. It was created by the selective breeding of light saddle horses with the smaller, heavier Norwegian Fjord horse to create small horses suitable for the equestrian vacation industry. The breeders' association, Association du Cheval Henson, was formed in 1983. In 1995 the studbook was closed to horses not born from Henson parents, and in 2003 the breed was officially recognised by the French government agencies for horse breeding. A hardy breed of horse, each winter the broodmares and youngstock from several breeders are let loose together to graze freely in the wetland reserves in France.

Lou Drapé is a legendary folkloric horse of the town of Aigues-Mortes in the Gard region, in the Petite Camargue marsh area of France. It is said to wander around the walls of the city at night and to take a large number of children on his back to abduct them. These children never return from this journey.

The Great Mare was a gigantic mare that served as a mount for giants in several Renaissance works. Stemming from medieval traditions inspired by Celtic mythology, she first appeared in The Grand and Priceless Chronicles of the Great and Enormous Giant Gargantua, written in 1532, in which Merlin created her from bones atop a mountain.

Several legendary horses are mentioned in the Jura Mountains. They are mainly white and winged horses walking near springs, flying to the top of the mountains, or frolicking in the Jura forests. There is also mention of headless horses, three-legged horses, or dangerous mounts that drown humans tempted to ride them in the Loue. These animals can be ridden during a wild hunt or simply block a passage, even playing tricks on those who ride them or kill them.

The Cauchois, or Norman bidet, is a breed of heavy draft horse native to the Pays de Caux, on the coast of the former Haute-Normandie region of France. Renowned for its ability to move at a high pace, it was much sought-after in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Although it was most often harnessed to heavy loads, such as the Compagnie Générale des Omnibus stagecoaches, it was also sometimes ridden by Cauchois peasants to market. They were exported to many parts of France.

Horse symbolism is the study of the representation of the horse in mythology, religion, folklore, art, literature and psychoanalysis as a symbol, in its capacity to designate, to signify an abstract concept, beyond the physical reality of the quadruped animal. The horse has been associated with numerous roles and magical gifts throughout the ages and in all regions of the world where human populations have come into contact with it, making it the most symbolically charged animal, along with the snake.