Related Research Articles

The European Convention on Human Rights is an international convention to protect human rights and political freedoms in Europe. Drafted in 1950 by the then newly formed Council of Europe, the convention entered into force on 3 September 1953. All Council of Europe member states are party to the convention and new members are expected to ratify the convention at the earliest opportunity.

The European Court of Human Rights, also known as the Strasbourg Court, is an international court of the Council of Europe which interprets the European Convention on Human Rights. The court hears applications alleging that a contracting state has breached one or more of the human rights enumerated in the convention or its optional protocols to which a member state is a party. The European Convention on Human Rights is also referred to by the initials "ECHR". The court is based in Strasbourg, France.

Loizidou v. Turkey is a landmark legal case regarding the rights of refugees wishing to return to their former homes and properties. The European Court of Human Rights ruled that Titina Loizidou, and consequently all other refugees, have the right to return to their former properties. The ECHR ruled that Turkey had violated Loizidou's human rights under Article I of Protocol I of the European Convention on Human Rights, that she should be allowed to return to her home and that Turkey should pay damages to her. Turkey initially ignored this ruling.

The Convention on Cybercrime, also known as the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime or the Budapest Convention, is the first international treaty seeking to address Internet and computer crime (cybercrime) by harmonizing national laws, improving investigative techniques, and increasing cooperation among nations. It was drawn up by the Council of Europe in Strasbourg, France, with the active participation of the Council of Europe's observer states Canada, Japan, the Philippines, South Africa and the United States.

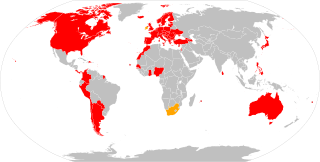

Sixteen European countries, along with Canada and Israel, have laws against Holocaust denial, the denial of the systematic genocidal killing of approximately six million Jews in Europe by Nazi Germany in the 1930s and 1940s. Many countries also have broader laws that criminalize genocide denial. Among the countries that ban Holocaust denial, Austria, Germany, Hungary, Poland and Romania also ban other elements associated with Nazism, such as the display of Nazi symbols.

The Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine, otherwise known as the European Convention on Bioethics or the European Bioethics Convention, is an international instrument aiming to prohibit the misuse of innovations in biomedicine and to protect human dignity. The Convention was opened for signature on 4 April 1997 in Oviedo, Spain and is thus otherwise known as the Oviedo Convention. The International treaty is a manifestation of the effort on the part of the Council of Europe to keep pace with developments in the field of biomedicine; it is notably the first multilateral binding instrument entirely devoted to biolaw. The Convention entered into force on 1 December 1999.

Additional Protocol to the Convention on Cybercrime, concerning the criminalisation of acts of a racist and xenophobic nature committed through computer systems is an additional protocol to the Council of Europe Convention on Cybercrime. This additional protocol was the subject of negotiations in late 2001 and early 2002. Final text of this protocol was adopted by the Council of Europe Committee of Ministers on 7 November 2002 under the title "Additional Protocol to the Convention on cybercrime, concerning the criminalisation of acts of a racist and xenophobic nature committed through computer systems, ("Protocol"). The Protocol opened on 28 January 2003 and entry into force is 1 March 2006. As of July 2017, 29 States have ratified the Protocol and a further 13 have signed the Protocol but have not yet followed with ratification.

Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights prohibits torture, and "inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment".

Article 3 – Prohibition of torture

No one shall be subjected to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

R (Carson) v Secretary of State for Work and Pensions and R v Secretary of State for Work and Pensions were a series of civil action court cases seeking judicial review of the British government's policies under the Human Rights Act 1998. They related to the right to property under Article 1 of the First Protocol and prohibition of discrimination under Article 14 of the convention. In Reynolds's case, there was also Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), the right to respect for "private and family life" to be considered, as well as Article 3 of the ECHR, the prohibition of torture, and "inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment".

Computer crime, or cybercrime in Canada, is an evolving international phenomenon. People and businesses in Canada and other countries may be affected by computer crimes that may, or may not originate within the borders of their country. From a Canadian perspective, 'computer crime' may be considered to be defined by the Council of Europe – Convention on Cybercrime. Canada contributed, and is a signatory, to this international of criminal offences involving the use of computers:

Andrejeva v. Latvia (55707/00) was a case decided by the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights in 2009. It concerned ex parte proceedings and discrimination in calculating retirement pensions for non-citizens of Latvia.

Pretty v. United Kingdom (2346/02) was a case decided by European Court of Human Rights in 2002.

Tănase v. Moldova was a case decided by the European Court of Human Rights in 2010.

Expression of racism in Latvia include racist discourse by politicians and in the media, as well as racially motivated attacks. European Commission against Racism and Intolerance notes some progress made in 2002–2007, mentioning also that a number of its earlier recommendations are not implemented or are only partially implemented. The UN Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance highlight three generally vulnerable groups and communities: ethnic Russians who immigrated to Latvia under USSR, the Roma community and recent non-European migrants. Besides, he notes a dissonance between "opinion expressed by most State institutions who view racism and discrimination as rare and isolated cases, and the views of civil society, who expressed serious concern regarding the structural nature of these problems".

Perinçek v. Switzerland is a 2013 judgment of the European Court of Human Rights concerning public statements by Doğu Perinçek, a nationalist political activist and member of the Talat Pasha Committee, who was convicted by a Swiss court for publicly denying the Armenian genocide.

Opinion 2/13 (2014) is an EU law case determined by the European Court of Justice, concerning the accession of the European Union to the European Convention on Human Rights, and more generally the relationship between the European Court of Justice and European Court of Human Rights.

Carson and Others v. The United Kingdom [2008] ECHR 1194 was heard by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), Fourth Section in Strasbourg on 4 November 2008 appeal from the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords before Lech Garlicki (President); Nicolas Bratza; Giovanni Bonello; Ljiljana Mijović; David Thór Björgvinsson; Ledi Bianku; Mihai Poalelungi.

Carson and Others v. The United Kingdom [2010] ECHR 338 was heard by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), in Strasbourg on 16 March 2010 on appeal from the European Court of Rights (ECHR), Fourth Section before Jean-Paul Costa (President), Christos Rozakis, Nicolas Bratza, Peer Lorenzen, Françoise Tulkens, Josep Casadevall, Karel Jungwiert, Nina Vajić, Dean Spielmann, Renate Jaeger, Danutė Jočienė, Ineta Ziemele, Isabelle Berro-Lefèvre, Päivi Hirvelä, Luis López Guerra, Mirjana Lazarova Trajkovska, Zdravka Kalaydjieva.

In the case of Hirsi Jamaa and Others v. Italy, before the European Court of Human Rights, the Grand Chamber of the Court found in February 2012 that by returning migrants to Libya, without examining their case, the state of Italy exposed the migrants to the risk of ill-treatment and amounted to a collective expulsion. The case concerned 24 migrants from Somalia end Eritrea that were travelling from Libya to Italy that were intercepted at sea by Italian authorities who sent them back to Libya.

Sargsyan v. Azerbaijan was an international human rights case regarding the rights of Armenian refugees displaced from former Soviet Azerbaijan because of the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh. The judgment of the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights on the case originated in an application against the Republic of Azerbaijan lodged with the Court under Article 34 of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms by Minas Sargsyan on 11 August 2006. He was forced to flee his home in the village of Gulistan in Shahumyan region of former Soviet Azerbaijan, together with his family, because of the Azerbaijani bombardments of the village and was not allowed to return and unable to get any compensation from the Azerbaijani authorities. Even though the applicant died in 2009, as did his widow, Lena Sargsyan, in 2014, his children, Vladimir and Tsovinar Sargsyan, represented him in court to continue the proceedings.

References

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations .(August 2010) |

- Judgment

- ECHR : Lehideux and Isorni v. France Publication : 1998-VII, no. 92 on the website of Netherlands Institute of Human Rights faculty of Law