A mycorrhiza is a symbiotic association between a fungus and a plant. The term mycorrhiza refers to the role of the fungus in the plant's rhizosphere, its root system. Mycorrhizae play important roles in plant nutrition, soil biology, and soil chemistry.

A mangrove is a shrub or tree that grows mainly in coastal saline or brackish water. Mangroves grow in an equatorial climate, typically along coastlines and tidal rivers. They have special adaptations to take in extra oxygen and to remove salt, which allow them to tolerate conditions that would kill most plants. The term is also used for tropical coastal vegetation consisting of such species. Mangroves are taxonomically diverse, as a result of convergent evolution in several plant families. They occur worldwide in the tropics and subtropics and even some temperate coastal areas, mainly between latitudes 30° N and 30° S, with the greatest mangrove area within 5° of the equator. Mangrove plant families first appeared during the Late Cretaceous to Paleocene epochs, and became widely distributed in part due to the movement of tectonic plates. The oldest known fossils of mangrove palm date to 75 million years ago.

A salt marsh, saltmarsh or salting, also known as a coastal salt marsh or a tidal marsh, is a coastal ecosystem in the upper coastal intertidal zone between land and open saltwater or brackish water that is regularly flooded by the tides. It is dominated by dense stands of salt-tolerant plants such as herbs, grasses, or low shrubs. These plants are terrestrial in origin and are essential to the stability of the salt marsh in trapping and binding sediments. Salt marshes play a large role in the aquatic food web and the delivery of nutrients to coastal waters. They also support terrestrial animals and provide coastal protection.

Pioneer species are resilient species that are the first to colonize barren environments, or to repopulate disrupted biodiverse steady-state ecosystems as part of ecological succession. A number of kinds of events can create good conditions for pioneers, including disruption by natural disasters, such as wildfire, flood, mudslide, lava flow or a climate-related extinction event or by anthropogenic habitat destruction, such as through land clearance for agriculture or construction or industrial damage. Pioneer species play an important role in creating soil in primary succession, and stabilizing soil and nutrients in secondary succession.

An endophyte is an endosymbiont, often a bacterium or fungus, that lives within a plant for at least part of its life cycle without causing apparent disease. Endophytes are ubiquitous and have been found in all species of plants studied to date; however, most of the endophyte/plant relationships are not well understood. Some endophytes may enhance host growth and nutrient acquisition and improve the plant's ability to tolerate abiotic stresses, such as drought, and decrease biotic stresses by enhancing plant resistance to insects, pathogens and herbivores. Although endophytic bacteria and fungi are frequently studied, endophytic archaea are increasingly being considered for their role in plant growth promotion as part of the core microbiome of a plant.

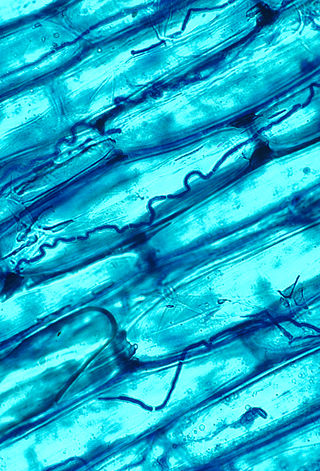

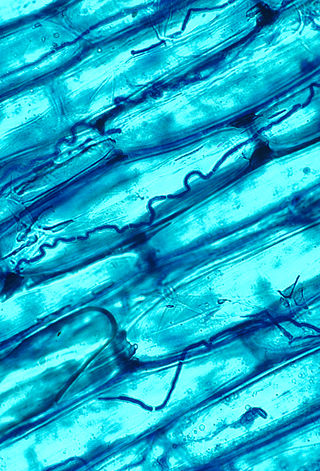

An arbuscular mycorrhiza (AM) is a type of mycorrhiza in which the symbiont fungus penetrates the cortical cells of the roots of a vascular plant forming arbuscules. Arbuscular mycorrhiza is a type of endomycorrhiza along with ericoid mycorrhiza and orchid mycorrhiza. They are characterized by the formation of unique tree-like structures, the arbuscules. In addition, globular storage structures called vesicles are often encountered.

Festuca ovina, sheep's fescue or sheep fescue, is a species of grass. It is sometimes confused with hard fescue.

Fusarium culmorum is a fungal plant pathogen and the causal agent of seedling blight, foot rot, ear blight, stalk rot, common root rot and other diseases of cereals, grasses, and a wide variety of monocots and dicots. In coastal dunegrass, F. culmorum is a nonpathogenic symbiont conferring both salt and drought tolerance to the plant.

Microbial inoculants, also known as soil inoculants or bioinoculants, are agricultural amendments that use beneficial rhizosphericic or endophytic microbes to promote plant health. Many of the microbes involved form symbiotic relationships with the target crops where both parties benefit (mutualism). While microbial inoculants are applied to improve plant nutrition, they can also be used to promote plant growth by stimulating plant hormone production. Although bacterial and fungal inoculants are common, inoculation with archaea to promote plant growth is being increasingly studied.

Leymus racemosus is a species of perennial wild rye known by the common name mammoth wild rye. It is native to southeastern and eastern Europe, Middle Asia, Caucasus, Siberia, China, Mongolia, New Zealand, and parts of North America. Culms are 50–100 cm long, and 10–12 mm in diameter.

Plant use of endophytic fungi in defense occurs when endophytic fungi, which live symbiotically with the majority of plants by entering their cells, are utilized as an indirect defense against herbivores. In exchange for carbohydrate energy resources, the fungus provides benefits to the plant which can include increased water or nutrient uptake and protection from phytophagous insects, birds or mammals. Once associated, the fungi alter nutrient content of the plant and enhance or begin production of secondary metabolites. The change in chemical composition acts to deter herbivory by insects, grazing by ungulates and/or oviposition by adult insects. Endophyte-mediated defense can also be effective against pathogens and non-herbivory damage.

Juncus roemerianus is a species of flowering plant in the rush family known by the common names black rush, needlerush, and black needlerush. It is native to North America, where its main distribution lies along the coastline of the southeastern United States, including the Gulf Coast. It occurs from New Jersey to Texas, with outlying populations in Connecticut, New York, Mexico, and certain Caribbean islands.

Leymus multicaulis, also known as manystem wild rye or manystem lyme grass, is a species of the genus Leymus. The species name of manystem wild rye, multicaulis, suggests the “many stems” of the species. Leymus multicaulis is considered a type of grass. Manystem wild rye has only one cotyledon in each of its seeds. The xylem and phloem within the roots are arranged in a ring pattern. The vascular bundles are scattered throughout the stem. These traits make Leymus multicaulis a monocot. Leymus multicaulis is a flowering plant, or angiosperm.

A mycorrhizal network is an underground network found in forests and other plant communities, created by the hyphae of mycorrhizal fungi joining with plant roots. This network connects individual plants together. Mycorrhizal relationships are most commonly mutualistic, with both partners benefiting, but can be commensal or parasitic, and a single partnership may change between any of the three types of symbiosis at different times.

Leymus mollis is a species of grass known by the common names American dune grass, American dune wild-rye, sea lyme-grass, strand-wheat, and strand grass. Its Japanese name is hamaninniku. It is native to Asia, where it occurs in Japan, China, Korea, and Russia, and northern parts of North America, where it occurs across Canada and the northern United States, as well as Greenland. It can also be found in Iceland.

An ectomycorrhiza is a form of symbiotic relationship that occurs between a fungal symbiont, or mycobiont, and the roots of various plant species. The mycobiont is often from the phyla Basidiomycota and Ascomycota, and more rarely from the Zygomycota. Ectomycorrhizas form on the roots of around 2% of plant species, usually woody plants, including species from the birch, dipterocarp, myrtle, beech, willow, pine and rose families. Research on ectomycorrhizas is increasingly important in areas such as ecosystem management and restoration, forestry and agriculture.

The root microbiome is the dynamic community of microorganisms associated with plant roots. Because they are rich in a variety of carbon compounds, plant roots provide unique environments for a diverse assemblage of soil microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and archaea. The microbial communities inside the root and in the rhizosphere are distinct from each other, and from the microbial communities of bulk soil, although there is some overlap in species composition.

Leymus chinensis, commonly known as false wheatgrass or Chinese rye grass, is a species of wild rye native to China, Korea, Mongolia and Russia.

Orchid mycorrhizae are endomycorrhizal fungi which develop symbiotic relationships with the roots and seeds of plants of the family Orchidaceae. Nearly all orchids are myco-heterotrophic at some point in their life cycle. Orchid mycorrhizae are critically important during orchid germination, as an orchid seed has virtually no energy reserve and obtains its carbon from the fungal symbiont.

Tripartite symbiosis is a type of symbiosis involving three species. This can include any combination of plants, animals, fungi, bacteria, or archaea, often in interkingdom symbiosis.