Related Research Articles

A cannon is a large-caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder during the late 19th century. Cannons vary in gauge, effective range, mobility, rate of fire, angle of fire and firepower; different forms of cannon combine and balance these attributes in varying degrees, depending on their intended use on the battlefield. A cannon is a type of heavy artillery weapon.

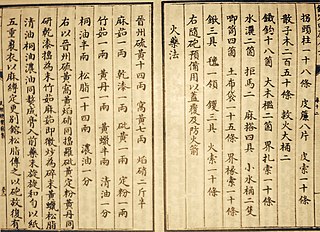

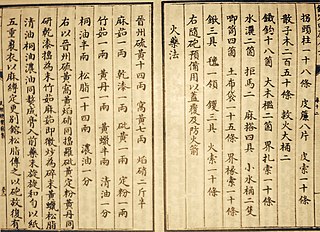

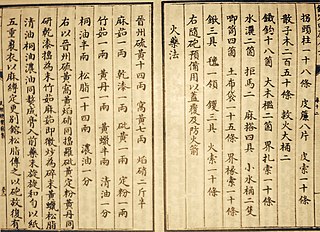

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon, and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). The sulfur and carbon act as fuels while the saltpeter is an oxidizer. Gunpowder has been widely used as a propellant in firearms, artillery, rocketry, and pyrotechnics, including use as a blasting agent for explosives in quarrying, mining, building pipelines, tunnels, and roads.

An arquebus is a form of long gun that appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire during the 15th century. An infantryman armed with an arquebus is called an arquebusier.

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually disappeared as the use of heavy armour declined, but musket continued as the generic term for smoothbore long guns until the mid-19th century. In turn, this style of musket was retired in the 19th century when rifled muskets using the Minié ball became common. The development of breech-loading firearms using self-contained cartridges and the first reliable repeating rifles produced by Winchester Repeating Arms Company in 1860 also led to their demise. By the time that repeating rifles became common, they were known as simply "rifles", ending the era of the musket.

The repeating crossbow, also known as the repeater crossbow, and the Zhuge crossbow due to its association with the Three Kingdoms-era strategist Zhuge Liang (181–234 AD), is a crossbow invented during the Warring States period in China that combined the bow spanning, bolt placing, and shooting actions into one motion.

The hand cannon, also known as the gonne or handgonne, is the first true firearm and the successor of the fire lance. It is the oldest type of small arms as well as the most mechanically simple form of metal barrel firearms. Unlike matchlock firearms it requires direct manual external ignition through a touch hole without any form of firing mechanism. It may also be considered a forerunner of the handgun. The hand cannon was widely used in China from the 13th century onward and later throughout Eurasia in the 14th century. In 15th century Europe, the hand cannon evolved to become the matchlock arquebus, which became the first firearm to have a trigger.

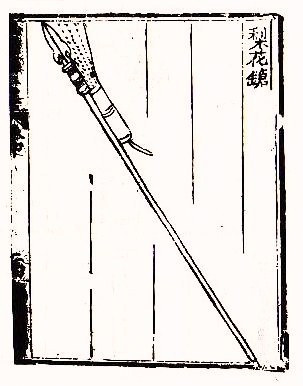

The fire lance was a gunpowder weapon and the ancestor of modern firearms. It first appeared in 10th–12th century China and was used to great effect during the Jin-Song Wars. It began as a small pyrotechnic device attached to a polearm weapon, used to gain a shock advantage at the start of a melee. As gunpowder improved, the explosive discharge was increased, and debris or pellets added, giving it some of the effects of a combination modern flamethrower and shotgun, but with a very short range, and only one shot. By the late 13th century, fire lance barrels had transitioned to metal material to better withstand the explosive blast, and the lance-point was discarded in favor of relying solely on the gunpowder blast. These became the first hand cannons.

The Battle of Tangdao (唐岛之战) was a naval engagement that took place in 1161 between the Jurchen Jin and the Southern Song Dynasty of China on the East China Sea. The conflict was part of the Jin-Song wars, and was fought near Tangdao Island. It was an attempt by the Jin to invade and conquer the Southern Song Dynasty, yet resulted in failure and defeat for the Jurchens. The Jin Dynasty navy was set on fire by huopao and fire arrows, suffering heavy losses. For this battle, the commander of the Song Dynasty squadron, Li Bao, faced the opposing commander Zheng Jia, the admiral of the Jin Dynasty. On the fate of Zheng Jia, the historical text of the Jin Shi states:

Zheng Jia did not know the sea routes well, nor much about the management of ships, and he did not believe. But all of a sudden they appeared, and finding us quite unready they hurled incendiary gunpowder projectiles on to our ships. So seeing all his ships going up in flames, and having no means of escape, Zheng Jia jumped into the sea and drowned.

Gunpowder artillery in the Middle Ages primarily consisted of the introduction of the cannon, large tubular firearms designed to fire a heavy projectile over a long distance. Guns, bombs, rockets and cannons were first invented in China during the Han and Song dynasties and then later spread to Europe and the Middle East during the period.

The history of firearms begins in 10th-century China, when tubes containing gunpowder and pellet projectiles were mounted on spears to make portable fire lances, operable by one person. This was later used effectively as a shock weapon in the Siege of De'an in 1132. In the 13th century, fire lance barrels were replaced with metal tubes and transformed into metal-barreled hand cannons. The technology gradually spread throughout Eurasia during the 14th century and evolved into flintlocks, blunderbusses, and other variants. The 19th and 20th centuries saw an acceleration in this evolution, with the introduction of the magazine, belt-fed weapons, metal cartridges, and the automatic firearm. Older firearms typically used black powder as a propellant, but modern firearms use smokeless powder or other propellants. Most modern firearms have rifled barrels.

The Huolongjing, also known as Huoqitu, is a Chinese military treatise compiled and edited by Jiao Yu and Liu Bowen of the early Ming dynasty (1368–1683) during the 14th century. The Huolongjing is primarily based on the text known as Huolong Shenqi Tufa, which no longer exists.

The Wujing Zongyao, sometimes rendered in English as the Complete Essentials for the Military Classics, is a Chinese military compendium written from around 1040 to 1044.

Gunpowder is the first explosive to have been developed. Popularly listed as one of the "Four Great Inventions" of China, it was invented during the late Tang dynasty while the earliest recorded chemical formula for gunpowder dates to the Song dynasty. Knowledge of gunpowder spread rapidly throughout Asia and Europe, possibly as a result of the Mongol conquests during the 13th century, with written formulas for it appearing in the Middle East between 1240 and 1280 in a treatise by Hasan al-Rammah, and in Europe by 1267 in the Opus Majus by Roger Bacon. It was employed in warfare to some effect from at least the 10th century in weapons such as fire arrows, bombs, and the fire lance before the appearance of the gun in the 13th century. While the fire lance was eventually supplanted by the gun, other gunpowder weapons such as rockets and fire arrows continued to see use in China, Korea, India, and this eventually led to its use in the Middle East, Europe, and Africa. Bombs too never ceased to develop and continued to progress into the modern day as grenades, mines, and other explosive implements. Gunpowder has also been used for non-military purposes such as fireworks for entertainment, or in explosives for mining and tunneling.

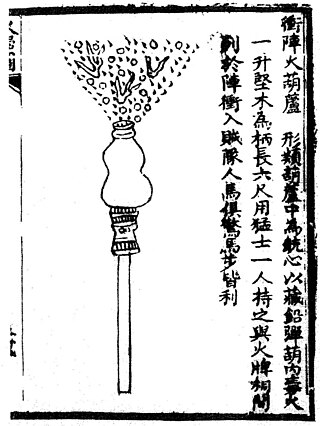

The first rockets were used as propulsion systems for arrows, and may have appeared as early as the 10th century in Song dynasty China. However more solid documentary evidence does not appear until the 13th century. The technology probably spread across Eurasia in the wake of the Mongol invasions of the mid-13th century. Usage of rockets as weapons before modern rocketry is attested to in China, Korea, India, and Europe. One of the first recorded rocket launchers is the "wasp nest" fire arrow launcher produced by the Ming dynasty in 1380. In Europe rockets were also used in the same year at the Battle of Chioggia. The Joseon kingdom of Korea used a type of mobile multiple rocket launcher known as the "Munjong Hwacha" by 1451.

A gun is a device designed to propel a projectile using pressure or explosive force. The projectiles are typically solid, but can also be pressurized liquid, or gas. Solid projectiles may be free-flying or tethered. A large-caliber gun is also called a cannon.

Hasan al-Rammah was a Syrian Arab chemist and engineer during the Mamluk Sultanate who studied gunpowders and explosives, and sketched prototype instruments of warfare, including the first torpedo. Al-Rammah called his early torpedo "an egg which moves itself and burns." It was made of two sheet-pans of metal fastened together and filled with naphtha, metal filings, and potassium nitrate. It was intended to move across the surface of the water, propelled by a large rocket and kept on course by a small rudder.

This is a timeline of the history of gunpowder and related topics such as weapons, warfare, and industrial applications. The timeline covers the history of gunpowder from the first hints of its origin as a Taoist alchemical product in China until its replacement by smokeless powder in the late 19th century.

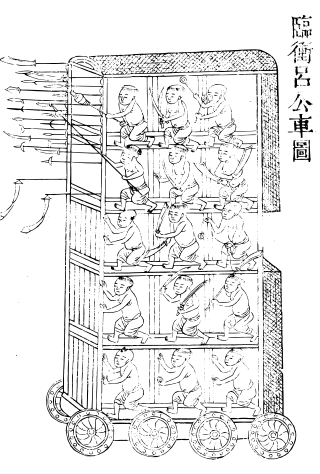

This is an overview of Chinese siege weapons.

In the history of gunpowder there are a range of theories about the transmission of the knowledge of gunpowder and guns from Imperial China to the rest of the world following the Song, Jin and Yuan dynasties. The earliest bronze guns found in China date back to the 13th century, with archaeological and textual evidence for previous nascent gunpowder technology developed beforehand. Scholars note the scarcity of records for firearms in the Middle East prior to the mid-14th century, and in Russia before the late 14th century, yet cannons already appeared in Europe by the early 14th century. Less accepted theories include gunpowder as being independently invented in the Middle East or South Asia.

The Zhenyuan Miaodao Yaolue is a Taoist alchemy text that dates to c. 950. It contains one of the earliest known references to gunpowder.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Partington, James Riddick. A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998, pp. 58-60

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Joseph Needham; Gwei-Djen Lu; Ling Wang (1987). Science and civilisation in China. Cambridge University Press. pp. 39–41. ISBN 978-0-521-30358-3.

- ↑ Partington, James Riddick. A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998, p. 43

- ↑ Kenneth Warren Chase (2003). Firearms: a global history to 1700. Cambridge University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-521-82274-9.

- ↑ Kelly DeVries (1992). Medieval military technology. University of Toronto Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-921149-74-3.

- ↑ Chisholm, Hugh (ed.) Gunpowder, Encyclopædia Britannica, 1910, p. 724

- ↑ Pan, Jixing. On the Origin of Rockets, T'oung Pao, Vol. 73, pg. 5–6

- ↑ Partington, James Riddick. A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998, p. 42

- ↑ Dana, Charles E., Notes on Cannon-Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 50, pg. 149

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 39.

- ↑ Iqtidar Alam Khan (2006). "The Indian Response to Firearms, 1300-1750". In Brenda J. Buchanan (ed.). Gunpowder, explosives and the state: a technological history. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-0-7546-5259-5.