The Roman triumph was a civil ceremony and religious rite of ancient Rome, held to publicly celebrate and sanctify the success of a military commander who had led Roman forces to victory in the service of the state or, in some historical traditions, one who had successfully completed a foreign war.

Proserpina or Proserpine is an ancient Roman goddess whose iconography, functions and myths are virtually identical to those of Greek Persephone. Proserpina replaced or was combined with the ancient Roman fertility goddess Libera, whose principal cult was housed in the Aventine temple of the grain-goddess Ceres, along with the wine god Liber.

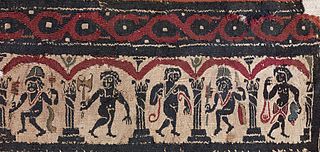

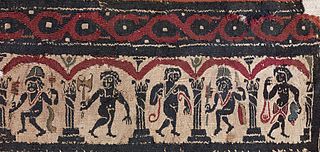

The Bacchanalia were unofficial, privately funded popular Roman festivals of Bacchus, based on various ecstatic elements of the Greek Dionysia. They were almost certainly associated with Rome's native cult of Liber, and probably arrived in Rome itself around 200 BC. Like all mystery religions of the ancient world, very little is known of their rites. They seem to have been popular and well-organised throughout the central and southern Italian peninsula.

In ancient Roman religion and mythology, Liber, also known as Liber Pater, was a god of viticulture and wine, male fertility and freedom. He was a patron deity of Rome's plebeians and was part of their Aventine Triad. His festival of Liberalia became associated with free speech and the rights attached to coming of age. His cult and functions were increasingly associated with Romanised forms of the Greek Dionysus/Bacchus, whose mythology he came to share.

The toga, a distinctive garment of ancient Rome, was a roughly semicircular cloth, between 12 and 20 feet in length, draped over the shoulders and around the body. It was usually woven from white wool, and was worn over a tunic. In Roman historical tradition, it is said to have been the favored dress of Romulus, Rome's founder; it was also thought to have originally been worn by both sexes, and by the citizen-military. As Roman women gradually adopted the stola, the toga was recognized as formal wear for male Roman citizens. Women found guilty of adultery and women engaged in prostitution might have provided the main exceptions to this rule.

Festivals in ancient Rome were a very important part in Roman religious life during both the Republican and Imperial eras, and one of the primary features of the Roman calendar. Feriae were either public (publicae) or private (privatae). State holidays were celebrated by the Roman people and received public funding. Games (ludi), such as the Ludi Apollinares, were not technically feriae, but the days on which they were celebrated were dies festi, holidays in the modern sense of days off work. Although feriae were paid for by the state, ludi were often funded by wealthy individuals. Feriae privatae were holidays celebrated in honor of private individuals or by families. This article deals only with public holidays, including rites celebrated by the state priests of Rome at temples, as well as celebrations by neighborhoods, families, and friends held simultaneously throughout Rome.

In ancient Roman religion, the Arval Brethren or Arval Brothers were a body of priests who offered annual sacrifices to the Lares and gods to guarantee good harvests. Inscriptions provide evidence of their oaths, rituals and sacrifices.

The Parilia or Palilia was an ancient Roman festival of rural character performed annually on 21 April, aimed at cleansing both sheep and shepherd. It was carried out in acknowledgment to the Roman deity Pales, a deity of uncertain gender who was a patron of shepherds and sheep.

The rituals of the Argei were archaic religious observances in ancient Rome that took place on March 16 and March 17, and again on May 14 or May 15. By the time of Augustus, the meaning of these rituals had become obscure even to those who practiced them. For the May rites, a procession of pontiffs, Vestals, and praetors made its way around a circuit of 27 stations, where at each they retrieved a figure fashioned into human form from rush, reed, and straw, resembling men tied hand and foot. After all the stations were visited, the procession, accompanied by the Flaminica Dialis in mourning guise, moved to the Pons Sublicius, the oldest known bridge in Rome, where the gathered figures were tossed into the Tiber River.

Lustratio was an ancient Greek and ancient Roman purification ritual. It included a procession and in some circumstances the sacrifice of a pig (sus), a ram (ovis), and a bull (taurus) (suovetaurilia). The name is the source of English "lustration".

The Compitalia was an annual festival in ancient Roman religion held in honor of the Lares Compitales, household deities of the crossroads, to whom sacrifices were offered at the places where two or more ways met.

Haloa or Alo (Ἁλῶα) was an Attic festival, celebrated principally at Eleusis, in honour of Demeter, protector of the fruits of the earth, of Dionysus, god of the grape and of wine, and Poseidon, god of the seashore vegetation. In Greek, the word hálōs (ἅλως) from which Haloa derives means “threshing-floor” or “garden.” While the general consensus is that it was a festival related to threshing—the process of loosening the edible part of cereal grain after harvest—some scholars disagree and argue that it was instead a gardening festival. Haloa focuses mainly on the “first fruits” of the harvest, partly as a grateful acknowledgement for the benefits the husbandmen received, partly as prayer that the next harvest would be plentiful. The festival was also called Thalysia or Syncomesteria.

Phallic processions are public celebrations featuring a phallus, a representation of an erect penis.

The cult of Dionysus was strongly associated with satyrs, centaurs, and sileni, and its characteristic symbols were the bull, the serpent, tigers/leopards, ivy, and wine. The Dionysia and Lenaia festivals in Athens were dedicated to Dionysus, as well as the phallic processions. Initiates worshipped him in the Dionysian Mysteries, which were comparable to and linked with the Orphic Mysteries, and may have influenced Gnosticism. Orpheus was said to have invented the Mysteries of Dionysus. It is possible that water divination was an important aspect of worship within the cult.

In ancient Roman religion and magic, the fascinus or fascinum was the embodiment of the divine phallus. The word can refer to phallus effigies and amulets, and to the spells used to invoke his divine protection. Pliny calls it a medicus invidiae, a "doctor" or remedy for envy or the evil eye.

In ancient Roman religion, sacra were transactions relating to the worship of the gods, especially sacrifice and prayer. They are either sacra privata or publica. The former were undertaken on behalf of the individual by himself, on behalf of the family by the pater familias, or on behalf of the gens by the whole body of the people.

The festival calendar of Classical Athens involved the staging of many festivals each year. This includes festivals held in honor of Athena, Dionysus, Apollo, Artemis, Demeter, Persephone, Hermes, and Herakles. Other Athenian festivals were based around family, citizenship, sacrifice, and women. There were at least 120 festival days each year.

The Aventine Triad is a modern term for the joint cult of the Roman deities Ceres, Liber and Libera. The cult was established c. 493 BC within a sacred district (templum) on or near the Aventine Hill, traditionally associated with the Roman plebs. Later accounts describe the temple building and rites as "Greek" in style. Some modern historians describe the Aventine Triad as a plebeian parallel and self-conscious antithesis to the Archaic Triad of Jupiter, Mars and Quirinus and the later Capitoline Triad of Jupiter, Minerva and Juno. The Aventine Triad, temple and associated ludi served as a focus of plebeian identity, sometimes in opposition to Rome's original ruling elite, the patricians.

The Amburbium was an ancient Roman festival for purifying the city; that is, a lustration (lustratio urbis). It took the form of a procession, perhaps along the old Servian Wall, though the length of 10 kilometers would seem impractical to circumambulate. If it was a distinct festival held annually, the most likely month is February, but no date is recorded and the ritual may have been performed as a "crisis rite" when needed.

Weddings in ancient Rome were a sacred ritual involving many religious practices. In order for the wedding to take place the bride and the groom or their fathers needed to consent to the wedding. Generally, the wedding would take place in June due to the god Juno. Weddings would never take place on days that were considered unlucky. During the wedding the groom would pretend to kidnap the bride. This was done to convince the household guardians, or lares, that the bride did not go willingly. Afterwards, the bride and the groom had their first sexual experiences on a couch called a lectus. In a Roman wedding both sexes had to wear specific clothing. Boys had to wear the toga virilis while the bride to wear a wreath, a veil, a yellow hairnet, chaplets of roses, seni crines, and the hasta caelibaris. All of the guests would wear the same clothes as the groom and the bride. The Romans believed that if bad omens showed up during a wedding it would indicate the couple was evil or unlucky. In order for a marriage to be successful there needed to be no evil omens and everyone must follow the traditional customs.