The Industrial Revolution, also known as the First Industrial Revolution, was a period of global transition of the human economy towards more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes that succeeded the Agricultural Revolution, starting from Great Britain and spreading to continental Europe and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going from hand production methods to machines; new chemical manufacturing and iron production processes; the increasing use of water power and steam power; the development of machine tools; and the rise of the mechanized factory system. Output greatly increased, and the result was an unprecedented rise in population and the rate of population growth. The textile industry was the first to use modern production methods, and textiles became the dominant industry in terms of employment, value of output, and capital invested.

Labour laws, labour code or employment laws are those that mediate the relationship between workers, employing entities, trade unions, and the government. Collective labour law relates to the tripartite relationship between employee, employer, and union.

Child labour is the exploitation of children through any form of work that interferes with their ability to attend regular school, or is mentally, physically, socially and morally harmful. Such exploitation is prohibited by legislation worldwide, although these laws do not consider all work by children as child labour; exceptions include work by child artists, family duties, supervised training, and some forms of work undertaken by Amish children, as well as by Indigenous children in the Americas.

Samuel Slater was an early English-American industrialist known as the "Father of the American Industrial Revolution", a phrase coined by Andrew Jackson, and the "Father of the American Factory System". In the United Kingdom, he was called "Slater the Traitor" and "Sam the Slate" because he brought British textile technology to the United States, modifying it for American use. He memorized the textile factory machinery designs as an apprentice to a pioneer in the British industry before migrating to the U.S. at the age of 21.

A cotton mill is a building that houses spinning or weaving machinery for the production of yarn or cloth from cotton, an important product during the Industrial Revolution in the development of the factory system.

Textile manufacture during the British Industrial Revolution was centred in south Lancashire and the towns on both sides of the Pennines in the United Kingdom. The main drivers of the Industrial Revolution were textile manufacturing, iron founding, steam power, oil drilling, the discovery of electricity and its many industrial applications, the telegraph and many others. Railroads, steamboats, the telegraph and other innovations massively increased worker productivity and raised standards of living by greatly reducing time spent during travel, transportation and communications.

The factory system is a method of manufacturing using machinery and division of labor. Because of the high capital cost of machinery and factory buildings, factories are typically privately owned by wealthy individuals or corporations who employ the operative labor. Use of machinery with the division of labor reduced the required skill-level of workers and also increased the output per worker.

The eight-hour day was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses of working time.

The Factory Acts were a series of acts passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom beginning in 1802 to regulate and improve the conditions of industrial employment.

The Lowell mill girls were young female workers who came to work in textile mills in Lowell, Massachusetts during the Industrial Revolution in the United States. The workers initially recruited by the corporations were daughters of New England farmers, typically between the ages of 15 and 35. By 1840, at the height of the Textile Revolution, the Lowell textile mills had recruited over 8,000 workers, with women making up nearly three-quarters of the mill workforce.

The Liberal Government of New Zealand was the first responsible government in New Zealand politics organised along party lines. The government formed following the founding of the Liberal Party and took office on 24 January 1891, and governed New Zealand for over 21 years until 10 July 1912. To date, it is the longest-serving government in New Zealand's history. The government was also historically notable for enacting significant social and economic changes, such as the Old Age Pensions Act and women's suffrage. One historian described the policies of the government as "a revolution in the relationship between the government and the people".

The Sadler Report, also known as the Report of the Select Committee on Factory Children's Labour or "the report of Mr Sadler’s Committee," was a report written in 1832 by Michael Sadler, the chairman of a UK Parliamentary committee considering a bill that limited the hours of work of children in textile mills and factories. In committee hearings carried out between the passage of the 1832 Reform Act and Parliament’s subsequent dissolution, Sadler had elicited testimony from factory workers, concerned medical men, and other bystanders. The report highlighted the poor working conditions and excessive working hours for children working in the factories. Time prevented balancing or contrary evidence from being called before Parliament was dissolved.

Michael Thomas Sadler was a British Tory Member of Parliament (MP) whose Evangelical Anglicanism and prior experience as a Poor Law administrator in Leeds led him to oppose Malthusian theories of population and their use to decry state provision for the poor.

The History of labour law in the United Kingdom concerns the development of UK labour law, from its roots in Roman and medieval times in the British Isles up to the present. Before the Industrial Revolution and the introduction of mechanised manufacture, regulation of workplace relations was based on status, rather than contract or mediation through a system of trade unions. Serfdom was the prevailing status of the mass of people, except where artisans in towns could gain a measure of self-regulation through guilds. In 1740 save for the fly-shuttle the loom was as it had been since weaving had begun. The law of the land was, under the Act of Apprentices 1563, that wages in each district should be assessed by Justices of the Peace. From the middle of the 19th century, through Acts such as the Master and Servant Act 1867 and the Employers and Workmen Act 1875, there became growing recognition that greater protection was needed to promote the health and safety of workers, as well as preventing unfair practices in wage contracts.

The history of labour law concerns the development of labour law as a way of regulating and improving the life of people at work. In the civilisations of antiquity, the use of slave labour was widespread. Some of the maladies associated with unregulated labour were identified by Pliny as "diseases of slaves."

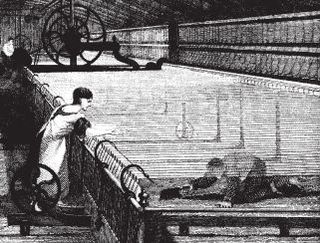

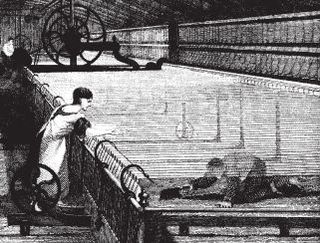

Scavengers were employed in 18th and 19th century in cotton mills, predominantly in the UK and the United States, to clean and recoup the area underneath a spinning mule. The cotton wastage that gathered on the floor was seen as too valuable for the owners to leave and one of the simplest solutions was to employ young children to work under the machinery. Many children suffered serious injuries while under the mules, with fingers, hands, and sometimes heads crushed by the heavy moving parts. Legislation introduced in 1819 tried to reduce working hours and improve conditions but there were still deaths recorded well beyond the middle of the 19th century.

A doffer is someone who removes ("doffs") bobbins, pirns or spindles holding spun fiber such as cotton or wool from a spinning frame and replaces them with empty ones. Historically, spinners, doffers, and sweepers each had separate tasks that were required in the manufacture of spun textiles. From the early days of the industrial revolution, this work, which requires speed and dexterity rather than strength, was often done by children. After World War I, the practice of employing children declined, ending in the United States in 1933. In modern textile mills, doffing machines have now replaced humans.

The Health and Morals of Apprentices Act 1802, sometimes known as the Factory Act 1802, was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom designed to improve conditions for apprentices working in cotton mills. The Act was introduced by Sir Robert Peel, who had become concerned in the issue after a 1784 outbreak of a "malignant fever" at one of his cotton mills, which he later blamed on 'gross mismanagement' by his subordinates.

The Cotton Mills and Factories Act 1819 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which was its first attempt to regulate the hours and conditions of work of children in the cotton industry. It was introduced by Sir Robert Peel, who had first introduced a bill on the matter in 1815. The 1815 bill had been instigated by Robert Owen, but the Act as passed was much weaker than the 1815 bill; the Act forbade the employment of children under 9; children aged 9–16 years were limited to 12 hours' work per day and could not work at night. There was no effective means of its enforcement, but it established the precedent for Parliamentary intervention on conditions of employment which was followed by subsequent Factory Acts.

Ellen Hooton was a ten-year-old girl from Wigan who gave testimony to the Central Board of His Majesty's Commissioners for inquiring into the Employment of Children in Factories, 1833. She had been working for several years at a spinning frame, in a cotton mill along with other children. She worked from 5.30 am till 8 pm, six days a week and nine hours on a Saturday. She absconded at least 10 times and was punished by her overseers.