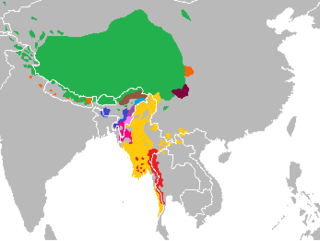

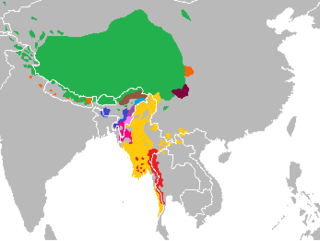

Sino-Tibetan, also cited as Trans-Himalayan in a few sources, is a family of more than 400 languages, second only to Indo-European in number of native speakers. The vast majority of these are the 1.3 billion native speakers of Sinitic languages. Other Sino-Tibetan languages with large numbers of speakers include Burmese and the Tibetic languages. Other languages of the family are spoken in the Himalayas, the Southeast Asian Massif, and the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau. Most of these have small speech communities in remote mountain areas, and as such are poorly documented.

Languages spoken in the Republic of India belong to several language families, the major ones being the Indo-Aryan languages spoken by 78.05% of Indians and the Dravidian languages spoken by 19.64% of Indians; both families together are sometimes known as Indic languages. Languages spoken by the remaining 2.31% of the population belong to the Austroasiatic, Sino–Tibetan, Tai–Kadai, and a few other minor language families and isolates. According to the People's Linguistic Survey of India, India has the second highest number of languages (780), after Papua New Guinea (840). Ethnologue lists a lower number of 456.

Bundeli or Bundelkhandi is an Indo-Aryan language spoken in the Bundelkhand region of central India. It belongs to the Central Indo-Aryan languages and is part of the Western Hindi subgroup.

Bagheli or Baghelkhandi is a Central Indo-Aryan language spoken in the Baghelkhand region of central India.

The Munda languages are a group of closely related languages spoken by about nine million people in India and Bangladesh. Historically, they have been called the Kolarian languages. They constitute a branch of the Austroasiatic language family, which means they are more distantly related to languages such as the Mon and Khmer languages, to Vietnamese, as well as to minority languages in Thailand and Laos and the minority Mangic languages of South China. Bhumij, Ho, Mundari, and Santali are notable Munda languages.

Bishnupriya Manipuri, also known as Bishnupriya Meitei or simply as Bishnupriya, is an Indo-Aryan lect belonging to the Bengali–Assamese linguistic sub-branch. It is a creole of Bengali language and Meitei language and it still retains its pre-Bengali features. It is spoken in parts of the Indian states of Assam, Tripura and Manipur as well as in the Sylhet Division of Bangladesh. It uses the Bengali-Assamese script as its writing system. Bishnupriya Manipuri, being a member of the Eastern Indo-Aryan languages, was evolved from Magadhi Prakrit. So, its origin is associated with Magadha realm. The Government of Tripura categorised Bishnnupriya Manipuri under the "Tribal Language Cell" of the State Council of Educational Research and Training. Its speakers are also given the "Other Backward Classes" status by the Assam Government and notably, there is no legal status of the Bishnupriyas in Manipur. In the 2020s, the Bishnupriya speaking people started demanding that the Assam Government should give them the status of “indigenous people” of Assam and treat the same like other indigenous communities of the state.

Bodo–Kacharis is a name used by anthropologist and linguists to define a collection of ethnic groups living predominantly in the Northeast Indian states of Assam, Tripura, and Meghalaya. These peoples are speakers of either Bodo–Garo languages or Assamese. Some Tibeto-Burman speakers who live closely in and around the Brahmaputra valley, such as the Mising people and Karbi people, are not considered Bodo–Kachari. Many of these peoples have formed early states in the late Medieval era of Indian history and came under varying degrees of Sanskritisation.

Indosphere is a term coined by the linguist James Matisoff for areas of Indian linguistic and cultural influence in South Asia and Southeast Asia. It is commonly used in areal linguistics in contrast with Sinosphere.

Vedic Sanskrit has a number of linguistic features which are alien to most other Indo-European languages. Prominent examples include: phonologically, the introduction of retroflexes, which alternate with dentals, and morphologically, the formation of gerunds. Some philologists attribute such features, as well as the presence of non-Indo-European vocabulary, to a local substratum of languages encountered by Indo-Aryan peoples in Central Asia (Bactria-Marghiana) and within the Indian subcontinent during Indo-Aryan migrations, including the Dravidian languages.

The People of Assam inhabit a multi-ethnic, multi-linguistic and multi-religious society. They speak languages that belong to four main language groups: Tibeto-Burman, Indo-Aryan, Tai-Kadai, and Austroasiatic. The large number of ethnic and linguistic groups, the population composition, and the peopling process in the state has led to it being called an "India in miniature".

Colin Paul Masica was an American linguist who was professor emeritus in the Department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations and the Department of Linguistics at the University of Chicago. Besides being a specialist in Indo-Aryan languages, much of his work was on the typological convergence of languages belonging to different linguistic families in the South Asian area and beyond, more broadly on this phenomenon in general, and on possible explanations for it and implications of it in connection with both linguistic and cultural history.

Hajong is an Indo-Aryan language with a possible Tibeto-Burman language substratum. It is spoken by approximately 80,000 ethnic Hajongs across the northeast of the Indian subcontinent, specifically in the states of Assam, Meghalaya, Arunachal Pradesh, and West Bengal in present-day India, and the divisions of Mymensingh and Sylhet in present-day Bangladesh. It is written in Bengali-Assamese script and Latin script. It has many Sanskrit loanwords. The Hajongs originally spoke a Tibeto-Burman language, but it later mixed with Assamese and Bengali.

Tadbhava is the Sanskrit word for one of three etymological classes defined by native grammarians of Middle Indo-Aryan languages, alongside tatsama and deśi words. A "tadbhava" is a word with an Indo-Aryan origin but which has evolved through language change in the Middle Indo-Aryan stage and eventually inherited into a modern Indo-Aryan language. In this sense, tadbhavas can be considered the native (inherited) vocabulary of modern Indo-Aryan languages.

Roughly 8.6 per cent of India's population is made up of "Scheduled Tribes" (STs), traditional tribal communities. Whilst most members of these tribes have adopted variants of Hinduism, Islam, or Christianity, a considerable number still adhere to their traditional tribal religions, with varying degrees of syncretism.

Languages of Nepal, referred to as Nepalese languages in the country's constitution, are the languages having at least an ancient history or origin inside the sovereign territory of Nepal spoken by Nepalis. The 2011 national census lists 123 languages spoken as a mother tongue in Nepal. Most belong to the Indo-Aryan and Sino-Tibetan language families.

South Asia is home to several hundred languages, spanning the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. It is home to the third most spoken language in the world, Hindi–Urdu; and the sixth most spoken language, Bengali. The languages in the region mostly comprise Indo-Iranic and Dravidian languages, and further members of other language families like Austroasiatic, and Tibeto-Burman languages.

Ahirwati is an Indo-Aryan dialect of India. It is spoken within the Ahirwal region located to the south-west of the capital Delhi. It belongs to the Rajasthani language group and is commonly taken to be a dialect of Mewati, but in many respects it is intermediate with the neighbouring varieties of Bangru and Bagri, and is especially close to Shekhawati.

The Dhimalish languages, Dhimal and Toto, are a small group of Sino-Tibetan languages spoken in Nepal, Bhutan, and the Jalpaiguri division of West Bengal, India.

The Tibeto-Burman languages are the non-Sinitic members of the Sino-Tibetan language family, over 400 of which are spoken throughout the Southeast Asian Massif ("Zomia") as well as parts of East Asia and South Asia. Around 60 million people speak Tibeto-Burman languages. The name derives from the most widely spoken of these languages, Burmese and the Tibetic languages, which also have extensive literary traditions, dating from the 12th and 7th centuries respectively. Most of the other languages are spoken by much smaller communities, and many of them have not been described in detail.

The Inner–Outer hypothesis of the subclassification of the Indo-Aryan language family argues for a division of the family into two groups, an Inner core and an Outer periphery, evidenced by shared traits of the languages falling into one of the two groups. Proponents of the theory generally believe the distinction to be the result of gradual migrations of Indo-Aryan speakers into India, with the inner languages representing a second wave of migration speaking a different dialect of Old Indo-Aryan, overtaking the first-wave speakers in the center and relegating them to the outer region.