Related Research Articles

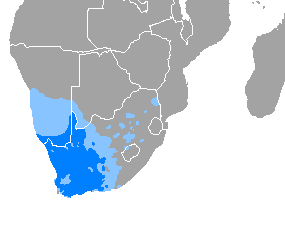

Afrikaans is a West Germanic language, spoken in South Africa, Namibia and Botswana, Zambia and Zimbabwe. It evolved from the Dutch vernacular of South Holland spoken by the predominantly Dutch settlers and enslaved population of the Dutch Cape Colony, where it gradually began to develop distinguishing characteristics in the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The Berber languages, also known as the Amazigh languages or Tamazight, are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. They comprise a group of closely related but mostly mutually unintelligible languages spoken by Berber communities, who are indigenous to North Africa. The languages are primarily spoken and not typically written. Historically, they have been written with the ancient Libyco-Berber script, which now exists in the form of Tifinagh. Today, they may also be written in the Berber Latin alphabet or the Arabic script, with Latin being the most pervasive.

Urdu is an Indo-Aryan language spoken chiefly in South Asia. It is the national language and lingua franca of Pakistan, where it is also an official language alongside English. In India, Urdu is an Eighth Schedule language, the status and cultural heritage of which are recognised by the Constitution of India; and it also has an official status in several Indian states. In Nepal, Urdu is a registered regional dialect and in South Africa it is a protected language in the constitution. It is also spoken as a minority language in Afghanistan and Bangladesh, with no official status.

A loanword is a word at least partly assimilated from one language into another language, through the process of borrowing. Borrowing is a metaphorical term that is well established in the linguistic field despite its acknowledged descriptive flaws: nothing is taken away from the donor language and there is no expectation of returning anything.

Bislama is an English-based creole language and one of the official languages of Vanuatu. It is the first language of many of the "Urban ni-Vanuatu" and the second language of much of the rest of the country's residents. The lyrics of "Yumi, Yumi, Yumi", the country's national anthem, are composed in Bislama.

Linguistic imperialism or language imperialism is occasionally defined as "the transfer of a dominant language to other people". This language "transfer" comes about because of imperialism. The transfer is considered to be a sign of power; traditionally military power but also, in the modern world, economic power. Aspects of the dominant culture are usually transferred along with the language. In spatial terms, indigenous languages are employed in the function of official (state) languages in Eurasia, while only non-indigenous imperial (European) languages in the "Rest of the World". In the modern world, linguistic imperialism may also be considered in the context of international development, affecting the standard by which organizations like the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank evaluate the trustworthiness and value of structural adjustment loans by virtue of views that are commonly foregrounded in English-language discourse and not neutral.

A standard language is a language variety that has undergone substantial codification of its grammar, lexicon, writing system, or other features. Typically, the varieties that undergo standardization are those associated with centers of commerce and government, used frequently by educated people and in news broadcasting, and taught widely in schools and to non-native learners of the language. Within a language community, standardization usually begins with a particular variety being selected, accepted by influential people, socially and culturally spread, established in opposition to competitor varieties, maintained, increasingly used in diverse contexts, and assigned high social prestige as a result of the variety becoming associated with the most successful people. As a sociological effect of these processes, most users of a standard dialect—and many users of other dialects of the same language—come to believe that the standard is inherently superior to, or consider it the linguistic baseline against which to judge, the other dialects, though this is rooted in social perceptions rather than objective realities.

In an English-speaking country, Standard English (SE) is the variety of English that has undergone substantial regularisation and is associated with formal schooling, language assessment, and official print publications, such as public service announcements and newspapers of record, etc. All linguistic features are subject to the effects of standardisation, including morphology, phonology, syntax, lexicon, register, discourse markers, pragmatics, as well as written features such as spelling conventions, punctuation, capitalisation and abbreviation practices. SE is local to nowhere: its grammatical and lexical components are no longer regionally marked, although many of them originated in different, non-adjacent dialects, and it has very little of the variation found in spoken or earlier written varieties of English. According to Peter Trudgill, Standard English is a social dialect pre-eminently used in writing that is distinguishable from other English dialects largely by a small group of grammatical "idiosyncrasies", such as irregular reflexive pronouns and an "unusual" present-tense verb morphology.

Tsat, also known as Utsat, Utset, Hainan Cham, or Huíhuī, is a tonal language spoken by 4,500 Utsul people in Yanglan (羊栏) and Huixin (回新) villages near Sanya, Hainan, China. Tsat is a member of the Malayo-Polynesian group within the Austronesian language family, and is one of the Chamic languages originating on the coast of present-day Vietnam.

Multilingualism is the use of more than one language, either by an individual speaker or by a group of speakers. It is believed that multilingual speakers outnumber monolingual speakers in the world's population. More than half of all Europeans claim to speak at least one language other than their mother tongue; but many read and write in one language. Being multilingual is advantageous for people wanting to participate in trade, globalization and cultural openness. Owing to the ease of access to information facilitated by the Internet, individuals' exposure to multiple languages has become increasingly possible. People who speak several languages are also called polyglots.

A mixed language, also referred to as a hybrid language, contact language, or fusion language, is a language that arises among a bilingual group combining aspects of two or more languages but not clearly deriving primarily from any single language. It differs from a creole or pidgin language in that, whereas creoles/pidgins arise where speakers of many languages acquire a common language, a mixed language typically arises in a population that is fluent in both of the source languages.

In sociolinguistics, language planning is a deliberate effort to influence the function, structure or acquisition of languages or language varieties within a speech community. Robert L. Cooper (1989) defines language planning as "the activity of preparing a normative orthography, grammar, and dictionary for the guidance of writers and speakers in a non-homogeneous speech community". Along with language ideology and language practices, language planning is part of language policy – a typology drawn from Bernard Spolsky's theory of language policy. According to Spolsky, language management is a more precise term than language planning. Language management is defined as "the explicit and observable effort by someone or some group that has or claims authority over the participants in the domain to modify their practices or beliefs" Language planning is often associated with government planning, but is also used by a variety of non-governmental organizations such as grass-roots organizations as well as individuals. Goals of such planning vary. Better communication through assimilation of a single dominant language can bring economic benefits to minorities but is also perceived to facilitate their political domination. It involves the establishment of language regulators, such as formal or informal agencies, committees, societies or academies to design or develop new structures to meet contemporary needs.

Indonesian and Malaysian Malay are two standardised varieties of the Malay language, the former used officially in Indonesia and the latter in Brunei, Malaysia and Singapore. Both varieties are generally mutually intelligible, yet there are noticeable differences in spelling, grammar, pronunciation and vocabulary, as well as the predominant source of loanwords. The differences can range from those mutually unintelligible with one another, to those having a closer familial resemblance. The regionalised and localised varieties of Malay can become a catalyst for intercultural conflict, especially in higher education.

The Republic of Vanuatu has the world's highest linguistic density per capita. Despite being a country with a population of less than 300,000, Vanuatu is home to 138 indigenous Oceanic languages.

Mwotlap is an Oceanic language spoken by about 2,100 people in Vanuatu. The majority of speakers are found on the island of Motalava in the Banks Islands, with smaller communities in the islands of Ra and Vanua Lava, as well as migrant groups in the two main cities of the country, Santo and Port Vila.

Swiss Standard German, or Swiss High German, referred to by the Swiss as Schriftdeutsch, or German: Hochdeutsch, is the written form of one of four official languages in Switzerland, besides French, Italian, and Romansh. It is a variety of Standard German, used in the German-speaking part of Switzerland and in Liechtenstein. It is mainly written, and rather less often spoken.

Albanian is an Indo-European language and the only surviving representative of the Albanoid branch, which belongs to the Paleo-Balkan group. Standard Albanian is the official language of Albania and Kosovo, and a co-official language in North Macedonia and Montenegro, as well as a recognized minority language of Italy, Croatia, Romania and Serbia. It is also spoken in Greece and by the Albanian diaspora, which is generally concentrated in the Americas, Europe and Oceania. Albanian is estimated to have as many as 7.5 million native speakers.

Dutch is a West Germanic language spoken by about 25 million people as a first language and 5 million as a second language. It is the third most widely spoken Germanic language, after its close relatives English and German. Afrikaans is a separate but mutually intelligible sister language of modern Dutch, and a daughter language of an earlier form of Dutch. It is spoken, to some degree, by at least 16 million people, mainly in South Africa and Namibia, evolving from the Cape Dutch dialects of Southern Africa.

The language of the court and government of the Ottoman Empire was Ottoman Turkish, but many other languages were in contemporary use in parts of the empire. The Ottomans had three influential languages, known as "Alsina-i Thalātha", that were common to Ottoman readers: Ottoman Turkish, Arabic and Persian. Turkish was spoken by the majority of the people in Anatolia and by the majority of Muslims of the Balkans except in Albania, Bosnia, and various Aegean Sea islands; Persian was initially a literary and high-court language used by the educated in the Ottoman Empire before being displaced by Ottoman Turkish; and Arabic, which was the legal and religious language of the empire, was also spoken regionally, mainly in Arabia, North Africa, Mesopotamia and the Levant.

The Torres–Banks languages form a linkage of Southern Oceanic languages spoken in the Torres Islands and Banks Islands of northern Vanuatu.

References

- ↑ Bowman, Kirk; Arocena, Felipe (2014). Lessons from Latin America: Innovations in Politics, Culture, and Development. Toronto, New York, Plymouth: University of Toronto Press. p. 79. ISBN 9781442605510.

- ↑ Chisita, Collence Takaingenhamo; Rusero, Alexander R.; Shoko, Munyaradzi (2016). "Leveraging Memory Institutions to Preserve Indigenous Knowledge in the Knowledge Age: Case of Zimbabwe". In Callison, Camille; Roy, Loriene; LeCheminant, Gretchen Alice (eds.). Indigenous Notions of Ownership and Libraries, Archives and Museums. Berlin, Boston: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 273. ISBN 9783110395860.

- ↑ Sheppard, Charles; Joubert, Jané; Saayman, Gina (1998). "Education and Language Profile". In Kok, Pieter (ed.). South Africa's Magnifying Glass: A Profile of Gauteng Province. Pretoria: HSRC Press. p. 101. ISBN 9780796918796.

- ↑ "Rwanda | Religion, Population, Language, & Capital | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-04-08.

- ↑ Werlen, Iwar (2007). "Receptive Multilingualism in Switzerland and the Case of Biel/Bienne". In ten Thije, Jan D.; Zeevaert, Ludger (eds.). Receptive Multilingualism: Linguistic Analyses, Language Policies, and Didactic Concepts. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing. p. 138. ISBN 9789027219268.

- ↑ Costa, Peter I. De (2016). The Power of Identity and Ideology in Language Learning: Designer Immigrants Learning English in Singapore. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. p. 55. ISBN 9783319302119.

- ↑ Duca, Patrick L. Del (2010). Choosing the Language of Transnational Deals: Practicalities, Policy, and Law Reform. Chicago, IL: American Bar Association. p. 157. ISBN 9781604429374.

- ↑ Leung, Janny H. C. (2019). Shallow Equality and Symbolic Jurisprudence in Multilingual Legal Orders. Oxford Studies in Language and Law. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 64. ISBN 9780190210342.

- ↑ Uwimana, Diane (17 September 2014). "English is now official language of Burundi". IWACU English News. Retrieved 2019-02-23.

- ↑ Macmillan, Palgrave (2017). The Statesman's Yearbook 2017: The Politics, Cultures and Economies of the World. London: Springer. p. 352. ISBN 9781349683987.

- ↑ Borsdorf, Axel; Stadel, Christoph (2015). The Andes: A Geographical Portrait. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. p. 142. ISBN 9783319035307.

- ↑ Leung, Janny H. C. (2019). Shallow Equality and Symbolic Jurisprudence in Multilingual Legal Orders. Oxford Studies in Language and Law. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 59. ISBN 9780190210342.

- ↑ Zipp, Lena (2014). Educated Fiji English: Lexico-grammar and variety status. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 13. ISBN 9789027270771.

- ↑ Gilles, Peter; Seela, Sebastian; Sieburg, Heinz; Wagner, Melanie (2011). "Languages and Identities". In IPSE-Identités Politiques Sociétés Espaces (ed.). Doing Identity in Luxembourg: Subjective Appropriations - Institutional Attributions - Socio-Cultural Milieus. Piscataway, NJ: Transcript Verlag. p. 91. ISBN 9783839416679.

- ↑ Leung, Janny H. C. (2019). Shallow Equality and Symbolic Jurisprudence in Multilingual Legal Orders. Oxford Studies in Language and Law. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 66–67. ISBN 9780190210342.

- ↑ Wanek, Alexander (1996). The State and Its Enemies in Papua New Guinea. Padstow, UK: Routledge. p. 92. ISBN 9781136779091.

- ↑ Michaelis, Susanne; Rosalie, Marcel (2009). "Loanwords in Seychelles Creole". In Haspelmath, Marin; Tadmor, Uri (eds.). Loanwords in the World's Languages: A Comparative Handbook. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. p. 216. ISBN 9783110218435.

- ↑ Mohns, William J. (2011). "The Digital Archive and Catalogues of the Vanuatu Cultural Center: Overview, Collaboration and Future Directions". In Taylor, John; Thieberger, Nick (eds.). Working Together in Vanuatu: Research Histories, Collaborations, Projects and Reflections. Canberra: ANU E Press. p. 142. ISBN 9781921862359.