Related Research Articles

Islamic philosophy is philosophy that emerges from the Islamic tradition. Two terms traditionally used in the Islamic world are sometimes translated as philosophy—falsafa, which refers to philosophy as well as logic, mathematics, and physics; and Kalam, which refers to a rationalist form of Scholastic Islamic theology which includes the schools of Maturidiyah, Ashaira and Mu'tazila.

Early Islamic philosophy or classical Islamic philosophy is a period of intense philosophical development beginning in the 2nd century AH of the Islamic calendar and lasting until the 6th century AH. The period is known as the Islamic Golden Age, and the achievements of this period had a crucial influence in the development of modern philosophy and science. For Renaissance Europe, "Muslim maritime, agricultural, and technological innovations, as well as much East Asian technology via the Muslim world, made their way to western Europe in one of the largest technology transfers in world history." This period starts with al-Kindi in the 9th century and ends with Averroes at the end of 12th century. The death of Averroes effectively marks the end of a particular discipline of Islamic philosophy usually called the Peripatetic Arabic School, and philosophical activity declined significantly in Western Islamic countries, namely in Islamic Spain and North Africa, though it persisted for much longer in the Eastern countries, in particular Persia and India where several schools of philosophy continued to flourish: Avicennism, Illuminationist philosophy, Mystical philosophy, and Transcendent theosophy.

Science in the medieval Islamic world was the science developed and practised during the Islamic Golden Age under the Abbasid Caliphate of Baghdad, the Umayyads of Córdoba, the Abbadids of Seville, the Samanids, the Ziyarids and the Buyids in Persia and beyond, spanning the period roughly between 786 and 1258. Islamic scientific achievements encompassed a wide range of subject areas, especially astronomy, mathematics, and medicine. Other subjects of scientific inquiry included alchemy and chemistry, botany and agronomy, geography and cartography, ophthalmology, pharmacology, physics, and zoology.

This is an alphabetical list of topics related to Islam, the history of Islam, Islamic culture, and the present-day Muslim world, intended to provide inspiration for the creation of new articles and categories. This list is not complete; please add to it as needed. This list may contain multiple transliterations of the same word: please do not delete the multiple alternative spellings—instead, please make redirects to the appropriate pre-existing Wikipedia article if one is present.

The three brothers Abū Jaʿfar, Muḥammad ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir ; Abū al‐Qāsim, Aḥmad ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir and Al-Ḥasan ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir, were Persian scholars who lived and worked in Baghdad. They are collectively known as the Banū Mūsā.

Islamic cosmology is the cosmology of Islamic societies. It is mainly derived from the Qur'an, Hadith, Sunnah, and current Islamic as well as other pre-Islamic sources. The Qur'an itself mentions seven heavens.

This is a list of articles in medieval philosophy.

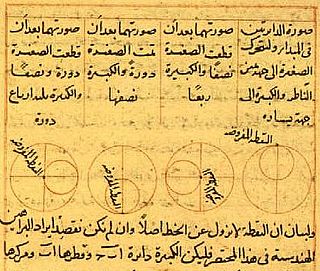

Muhammad ibn Muhammad ibn al-Hasan al-Tusi, also known as Nasir al-Din al-Tusi or simply as (al-)Tusi, was a Persian polymath, architect, philosopher, physician, scientist, and theologian. Nasir al-Din al-Tusi was a well published author, writing on subjects of math, engineering, prose, and mysticism. Additionally, al-Tusi made several scientific advancements. In astronomy, al-Tusi created very accurate tables of planetary motion, an updated planetary model, and critiques of Ptolemaic astronomy. He also made strides in logic, mathematics but especially trigonometry, biology, and chemistry. Nasir al-Din al-Tusi left behind a great legacy as well. Tusi is widely regarded as one of the greatest scientists of medieval Islam, since he is often considered the creator of trigonometry as a mathematical discipline in its own right. The Muslim scholar Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) considered Tusi to be the greatest of the later Persian scholars. There is also reason to believe that he may have influenced Copernican heliocentrism.

Sharh al-Isharat is a philosophical commentary on Avicenna's book Al-isharat wa al-tanbihat. This commentary has been written by Nasir al-Din al-Tusi in defense of the philosophy of Avicenna in response to the criticism made against him by Fakhr al-Din al-Razi in a book of the same title.

Isa ibn Yazid al-Juludi was a ninth century military commander for the Abbasid Caliphate. He twice served as governor of Egypt, from 827 to 829 and again from 829 to 830.

Ismā‘īl ibn ‘Alī, Abū Sahl al-Nawbakhtī was the great scholar of the Imamah, and the uncle of Abu Muhammad al-Hasan ibn Musa al-Nawbakhti. Abū Sahl died in 923.

Abū Muḥammad al-Ḥasan b Mūsā an-Nawbakhtī was a Persian and leading Shī'ī theologian and philosopher in the first half of the 10th century. The Nawbakhtī family boasted a number of scholars famous at the Abbāsid court of Hārūn al-Rashīd. Al-Ḥasan ibn Mūsa is best known for his book about the Shi'a sects titled Firaq al-Shi'a.

References

- Haque, Amber (2004). "Psychology from Islamic Perspective: Contributions of Early Muslim Scholars and Challenges to Contemporary Muslim Psychologists". Journal of Religion and Health. 43 (4): 357–377. doi:10.1007/s10943-004-4302-z. S2CID 38740431.

- Saoud, R (March 2004). "The Arab Contribution to the Music of the Western World" (PDF). Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilization. Retrieved 2007-01-12.

- Deuraseh, Nurdeen; Abu Talib, Mansor (2005). "Mental health in Islamic medical tradition". The International Medical Journal. 4 (2): 76–79.

- Martin-Araguz, A.; Bustamante-Martinez, C.; Fernandez-Armayor, Ajo V.; Moreno-Martinez, J. M. (2002). "Neuroscience in al-Andalus and its influence on medieval scholastic medicine". Revista de Neurología. 34 (9): 877–892. doi:10.33588/rn.3409.2001382. PMID 12134355.

- Iqbal, Muhammad (1934). "The Spirit of Muslim Culture". The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam. Oxford University Press. OCLC 934310562.

- Rosenthal, Franz (1950). "Al-Asturlabi and as-Samaw'al on Scientific Progress". Osiris. 9: 555–564. doi:10.1086/368538. S2CID 224796639.

- "Additional Lifespan Development Topics: Theories on Death and Dying" (PDF). McGraw-Hill Companies. 2009. p. 4.

- Khaleefa, Omar (Summer 1999). "Who Is the Founder of Psychophysics and Experimental Psychology?". American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences. 16 (2).

- Blair, Betty (1995). "Behind Soviet Aeronauts". Azerbaijan International. 3 (3).

- Bond, Peter (7 April 2003). "Obituary: Lt-Gen Kerim Kerimov". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2009-04-13.

- Ahmed, Akbar S. (1984). "Al-Beruni: The First Anthropologist". RAIN. 60 (60): 9–10. doi:10.2307/3033407. JSTOR 3033407.

- Gandz, Solomon (1936). "The sources of al-Khwarizmi's algebra". Osiris. 1: 263–277. doi:10.1086/368426. S2CID 60770737.

- Nanisetti, Serish (June 23, 2006). "Father of algorithms and algebra". The Hindu . Archived from the original on October 1, 2007.

- "Farouk El-Baz: With Apollo to the Moon". IslamOnline. Archived from the original on 2008-02-21.

- Rozhanskaya, Mariam; Levinova, I. S. (1996). "Statics". In Rashed, Roshdi (ed.). Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science. Vol. 2. London: Routledge. p. 642.

- Al-Khalili, Jim (2009-01-04). "The 'first true scientist'". BBC News. Retrieved 2014-04-11.

- Thiele, Rüdiger (2005). "In Memoriam: Matthias Schramm". Arabic Sciences and Philosophy. 15. Cambridge University Press: 329–331. doi:10.1017/S0957423905000214. S2CID 231738109.

- Al Deek, Mahmoud (November–December 2004). "Ibn Al-Haitham: Master of Optics, Mathematics, Physics and Medicine". Al Shindagah.

- Mowlana, H. (2001). "Information in the Arab World". Cooperation South Journal. 1.

- Abdalla, Mohamad (Summer 2007). "Ibn Khaldun on the Fate of Islamic Science after the 11th Century". Islam & Science. 5 (1): 61–7.

- Ahmed, Salahuddin (1999). A Dictionary of Muslim Names. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 1-85065-356-9.

- Akhtar, S. W. (1997). "The Islamic Concept of Knowledge". Al-Tawhid: A Quarterly Journal of Islamic Thought & Culture. 12 (3).

- Oweiss, I. M. (1988). "Ibn Khaldun, the Father of Economics". Arab Civilization: Challenges and Responses. New York University Press. ISBN 0-88706-698-4.

- Boulakia, Jean David C. (1971). "Ibn Khaldun: A Fourteenth-Century Economist". The Journal of Political Economy. 79 (5): 1105–1118. doi:10.1086/259818. S2CID 144078253.

- Sen, Amartya (2000). "A Decade of Human Development". Journal of Human Development. 1 (1): 17–23. doi:10.1080/14649880050008746. S2CID 17023095.

- ul Haq, Mahbub (1995). Reflections on Human Development. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-510193-6.

- Safavi-Abbasi, S; Brasiliense, LBC; Workman, RK (2007). "The fate of medical knowledge and the neurosciences during the time of Genghis Khan and the Mongolian Empire". Neurosurgical Focus. 23 (1): 3. doi: 10.3171/FOC-07/07/E13 . S2CID 8405572.

- Nasr, Seyyed Hossein; Leaman, Oliver (1996). History of Islamic Philosophy. Routledge. pp. 315, 1022–1023. ISBN 0-415-13159-6.

- Russell, G. A. (1994). The 'Arabick' Interest of the Natural Philosophers in Seventeenth-Century England. Brill Publishers. pp. 224–262. ISBN 90-04-09459-8.

- Siddique, Md. Zakaria (2009). "Reviewing the Phenomenon of Death—A Scientific Effort from the Islamic World". Death Studies. 33 (2): 190–195. doi:10.1080/07481180802602824. S2CID 142745624.

- Meyers, Karen; Golden, Robert N.; Peterson, Fred (2009). The Truth about Death and Dying. Infobase Publishing. p. 106. ISBN 9781438125817.

- Ahmed, Akbar (2002). "Ibn Khaldun's Understanding of Civilizations and the Dilemmas of Islam and the West Today". Middle East Journal. 56 (1): 5.

- Khan, Zafarul-Islam (15 January 2000). "At The Threshold Of A New Millennium – II". The Milli Gazette.

- Gari, L. (2002). "Arabic Treatises on Environmental Pollution up to the End of the Thirteenth Century". Environment and History. 8 (4): 475–488. doi:10.3197/096734002129342747.