Karl Ludwig Michelet was a German philosopher. He was born and died in Berlin.

Nicole Oresme, also known as Nicolas Oresme, Nicholas Oresme, or Nicolas d'Oresme, was a French philosopher of the later Middle Ages. He wrote influential works on economics, mathematics, physics, astrology, astronomy, philosophy, and theology; was Bishop of Lisieux, a translator, a counselor of King Charles V of France, and one of the most original thinkers of 14th-century Europe.

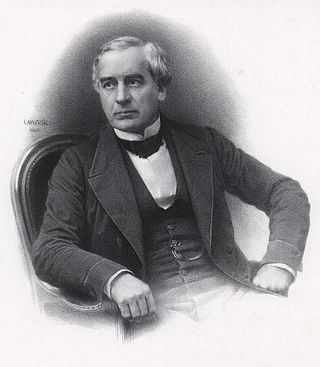

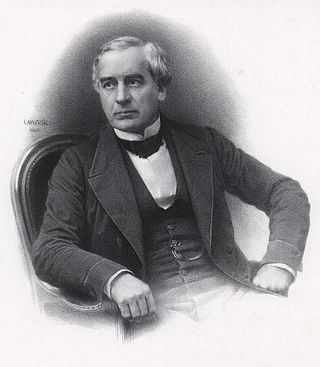

Jules Barthélemy-Saint-Hilaire was a French philosopher, journalist, statesman, and possible illegitimate son of Napoleon I of France.

On the Heavens is Aristotle's chief cosmological treatise: written in 350 BC, it contains his astronomical theory and his ideas on the concrete workings of the terrestrial world. It should not be confused with the spurious work On the Universe.

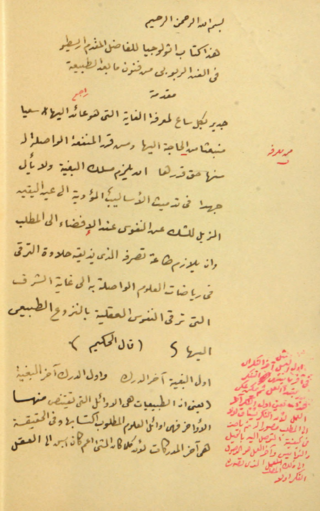

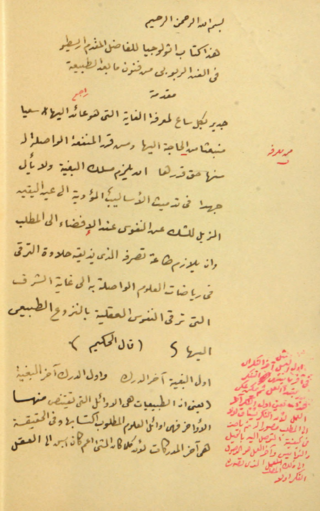

The Theology of Aristotle, also called Theologia Aristotelis is a paraphrase in Arabic of parts of Plotinus' Six Enneads along with Porphyry's commentary. It was traditionally attributed to Aristotle, but as this attribution is certainly untrue it is conventional to describe the author as "Pseudo-Aristotle". It had a significant effect on early Islamic philosophy, due to Islamic interest in Aristotle. Al-Kindi (Alkindus) and Avicenna, for example, were influenced by Plotinus' works as mediated through the Theology and similar works. The translator attempted to integrate Aristotle's ideas with those of Plotinus — while trying to make Plotinus compatible with Christianity and Islam, thus yielding a unique synthesis.

Laurent de Premierfait was a Latin poet, a humanist and in the first rank of French language translators of the fifteenth century, during the time of king Charles VI of France. To judge from the uses made of Du cas des nobles hommes et femmes in England, and the sheer number of surviving manuscripts of it, it was extremely popular in Western Europe throughout the fifteenth century. Laurent made two translations of the Boccaccio work, the second considerably more free. A large percentage of surviving manuscripts are carefully written and illuminated with illustrations.

Louis Chevalier was a French historian with interests in geography, demography and sociology. Much of his work was devoted to the history of French culture and Paris.

Antoine Vérard was a late 15th-century and early 16th-century French publisher, bookmaker and bookseller.

Pierre Chaunu was a French historian. His specialty was Latin American history; he also studied French social and religious history of the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. A leading figure in French quantitative history as the founder of "serial history", he was professor emeritus at Paris IV-Sorbonne, a member of the Institut de France, and a commander of the Légion d'Honneur. A convert to Protestantism from Roman Catholicism, he defended his far-right views most notably in a longtime column in Le Figaro and on Radio Courtoisie.

Jean-Baptiste Duroselle was a French historian and professor. He had initially considered an army career or study of geography, but his poor skills in mathematics and drawing led him to turn to historical study. Pierre Renouvin's course fascinated him, and he became his assistant in 1945. He went on to teach at University of Saarbrücken from 1950 to 1957 and returned to the Sorbonne afterward. Between 1977 and 1979, he was visiting professor of the history of international relations at the Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva. Duroselle's writings include La Decadence (1980), L'Abime (1985), and others. Duroselle was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1975. He was noted for his study of international relations and won a 1982 Balzan Prize for Social Sciences for his work.

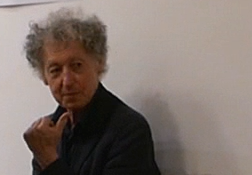

Robert Muchembled is a French historian. In 1967, he passed the Agrégation in history. In 1985 he was awarded a doctorate for his thesis on attitudes to violence and society in Artois between 1440 and 1600. In 1986 he became Professor of Modern History at Paris 13 University. He has written notably about witchcraft, violence and sexuality. Some of his works have been translated into English, German, Spanish, Italian, German, Dutch, Croatian, Modern Greek, Turkish, Chinese, Japanese, Polish and Portuguese.

Lambros Couloubaritsis is a Greek-born Belgian philosopher.

The Book of the 24 Philosophers is a philosophical and theological medieval text of uncertain authorship.

Albert Pierre Jules Joseph Bayet was a French sociologist, professor at both the Sorbonne and the École pratique des hautes études.

Antoine Le Roux de Lincy was a 19th-century French librarian, romanist and medievalist.

Albert Bertrand Hemmerdinger was a French historian who specialised in ancient history.

Georges-Henri Bousquet was a 20th-century French jurist, economist and Islamologist. He was a professor of law at the Faculty of Law of the University of Algiers where he was a specialist in the sociology of North Africa. He is also known for his translation work of the great Muslim authors, Al-Ghazali, a theologian who died in 1111 and Tunisian historian Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406). He was known as a polyglot, spoke several European languages and Eastern ones.

Pierre Birnbaum is a French historian and sociologist.

Patrick Boucheron is a French historian. He previously taught medieval history at the École normale supérieure and the University of Paris. He is a professor of history at the Collège de France. He is the author of 12 books and or the editor of 5 books. His 2017 book, Histoire mondiale de la France, compiled work by 122 historians and became an unexpected bestseller, with more than 110 000 copies sold. From 2017 to 2020, he hosted Quand l'histoire fait dates, a TV program of 22 episodes which explored different important dates in world history.

Laure Darcos is a French politician of Soyons Libres (SL) who has been a member of the Senate since the 2017 elections, representing Essonne.