Related Research Articles

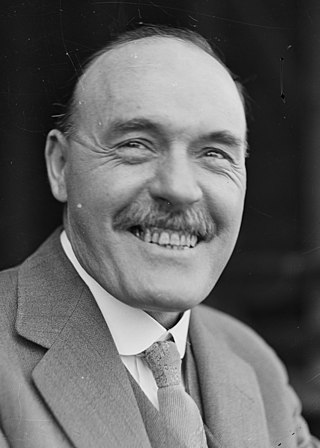

John Thomas Lang, usually referred to as J. T. Lang during his career and familiarly known as "Jack" and nicknamed "The Big Fella", was an Australian politician, mainly for the New South Wales Branch of the Labor Party. He twice served as the 23rd Premier of New South Wales from 1925 to 1927 and again from 1930 to 1932. He was dismissed by the Governor of New South Wales, Sir Philip Game, at the climax of the 1932 constitutional crisis and resoundingly lost the resulting election and subsequent elections as Leader of the Opposition. He later formed Lang Labor that contested federal and state elections and was briefly a member of the Australian House of Representatives.

His Majesty's Government of the Virgin Islands is the democratically elected government of the British Overseas Territory of the British Virgin Islands. It is regulated by the Constitution of the British Virgin Islands.

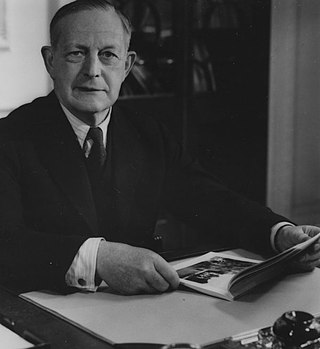

James Henry Scullin was an Australian politician and trade unionist who served as the ninth prime minister of Australia, from 1929 to 1932, holding office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP). During his tenure he also briefly served as the 13th treasurer of Australia from 1930 to 1931. Scullin was the first Catholic, as well as the first Irish-Australian, to serve as Prime Minister of Australia. His time in office was primarily categorised by the Wall Street Crash of 1929 which transpired just two days after his swearing in, which would herald the beginning of the Great Depression in Australia. Despite this Scullin remained a leading figure in the Labor movement throughout his lifetime, and was an éminence grise in various capacities for the party until his retirement from federal parliament in 1949.

Tertiary education fees in Australia are payable for courses at tertiary education institutions. For most of the "domestic students", the Commonwealth government provides loans, subsidies, social security welfare payments & benefits to relieve the cost of tertiary education, these benefits are not available to the "international students". Some domestic students are supported by the government and are required to pay only part of the cost of tuition, called the "student contribution", and the government pays the balance. Some government supported students can defer payment of their contribution as a HECS-HELP loan. Other domestic students are full fee-paying and do not receive direct government contribution to the cost of their education. Some domestic students in full fee courses can obtain a FEE-HELP loan from the Australian government up to a lifetime limit of $150,000 for medicine, dentistry and veterinary science programs and $104,440 for all other programs.

Debt restructuring is a process that allows a private or public company or a sovereign entity facing cash flow problems and financial distress to reduce and renegotiate its delinquent debts to improve or restore liquidity so that it can continue its operations.

In many states with political systems derived from the Westminster system, a consolidated fund or consolidated revenue fund is the main bank account of the government. General taxation is taxation paid into the consolidated fund, and general spending is paid out of the consolidated fund.

A creditor or lender is a party that has a claim on the services of a second party. It is a person or institution to whom money is owed. The first party, in general, has provided some property or service to the second party under the assumption that the second party will return an equivalent property and service. The second party is frequently called a debtor or borrower. The first party is called the creditor, which is the lender of property, service, or money.

The Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) is the independent federal agency responsible for the management of federal Australian elections, by-elections and referendums.

Law enforcement in Australia is one of the three major components of the country's justice system, along with courts and corrections. Law enforcement officers are employed by all three levels of government – federal, state/territory, and local.

The Constitution Alteration Bill 1928, was approved by referendum on 17 November 1928. The amendment to the Australian constitution concerned financial relations between the Commonwealth of Australia and the Australian states. It became law on 13 February 1929.

The referendum of 13 April 1910 approved an amendment to the Australian constitution. The referendum was for practical purposes a vote on the Constitution Alteration Bill 1909, which after being approved in the referendum received the Royal Assent on 6 August 1910.

Federalism was adopted, as a constitutional principle, in Australia on 1 January 1901 – the date upon which the six self-governing Australian Colonies of New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania, Victoria, and Western Australia federated, formally constituting the Commonwealth of Australia. It remains a federation of those six original States under the Constitution of Australia.

Australia suffered badly during the period of the Great Depression of the 1930s. The Depression began with the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and rapidly spread worldwide. As in other nations, Australia suffered years of high unemployment, poverty, low profits, deflation, plunging incomes, and lost opportunities for economic growth and personal advancement.

Sir Otto Ernst Niemeyer was a British banker and civil servant. He served as a director of the Bank of England from 1938 to 1952 and a director of the Bank for International Settlements from 1931 to 1965.

The 1932 dismissal of Premier Jack Lang by New South Wales Governor Philip Game was the first real constitutional crisis in Australia. Lang remains the only Australian premier to be removed from office by his governor, using the reserve powers of the Crown.

Ombudsmen in Australia are independent agencies who assist when a dispute arises between individuals and industry bodies or government agencies. Government ombudsman services are free to the public, like many other ombudsman and dispute resolution services, and are a means of resolving disputes outside of the court systems. Australia has an ombudsman assigned for each state; as well as an ombudsman for the Commonwealth of Australia. As laws differ between states just one process, or policy, cannot be used across the Commonwealth. All government bodies are within the jurisdiction of the ombudsman.

The Corporation of Foreign Bondholders was a British association established in London in 1868 by private holders of debt securities issued by foreign governments, states and municipalities. In an era before extensive financial regulation.and of wide sovereign immunity, it provided a forum for British creditors to co-ordinate their actions during the financial boom from the 1860s to the 1950s. It created an important mechanism through which investors could formulate proposals to deal with the government defaults, particularly in the Great Depression following the 1929 Wall Street crash, including several early debt restructurings.

The Australian government debt is the amount owed by the Australian federal government. The Australian Office of Financial Management, which is part of the Treasury Portfolio, is the agency which manages the government debt and does all the borrowing on behalf of the Australian government. Australian government borrowings are subject to limits and regulation by the Loan Council, unless the borrowing is for defence purposes or is a 'temporary' borrowing. Government debt and borrowings have national macroeconomic implications, and are also used as one of the tools available to the national government in the macroeconomic management of the national economy, enabling the government to create or dampen liquidity in financial markets, with flow on effects on the wider economy.

The Premiers' Plan was a deflationary economic policy agreed by a meeting of the Premiers of the Australian states in June 1931 to combat the Great Depression in Australia that sparked the 1931 Labor split.

The Puerto Rican government-debt crisis was a financial crisis affecting the government of Puerto Rico. The crisis began in 2014 when three major credit agencies downgraded several bond issues by Puerto Rico to "junk status" after the government was unable to demonstrate that it could pay its debt. The downgrading, in turn, prevented the government from selling more bonds in the open market. Unable to obtain the funding to cover its budget imbalance, the government began using its savings to pay its debt while warning that those savings would eventually be exhausted. To prevent such a scenario, the United States Congress enacted a law known as PROMESA, which appointed an oversight board with ultimate control over the Commonwealth's budget. As the PROMESA board began to exert that control, the Puerto Rican government sought to increase revenues and reduce its expenses by increasing taxes while curtailing public services and reducing government pensions. These measures provoked social distrust and unrest, further compounding the crisis. In August 2018, a debt investigation report of the Financial Oversight and management board for Puerto Rico reported the Commonwealth had $74 billion in bond debt and $49 billion in unfunded pension liabilities as of May 2017. Puerto Rico officially exited bankruptcy on March 15, 2022.

References

- 1 2 3 Budget office: The Australian Loan Council

- 1 2 "Australian Loan Council". Australian Government Directory. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 licence.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 licence. - ↑ Kirkwood, L; et al. (yes) (2006). Economics for the Real World 2 (second ed.). Melbourne: Pearson Education Australia.

- ↑ "Loan council allocation (General Government)". Victorian State Government. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 licence.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 licence. - ↑ Josie Castle "The 1920s" in R. Willis, et al (eds.) (1982), p. 253

- ↑ e.g., Commonwealth and States Financial Agreement Ratification Act of 1927 (Qld)

- ↑ Mason, K. J. (1992). Experience of Nationhood (third ed.). McGraw Hill.

- ↑ "Validity of Enforcement Act". The Canberra Times. 22 April 1932.