A mnemonicdevice, or memory device, is any learning technique that aids information retention or retrieval (remembering) in the human memory for better understanding.

African art describes the modern and historical paintings, sculptures, installations, and other visual culture from native or indigenous Africans and the African continent. The definition may also include the art of the African diasporas, such as: African American, Caribbean or art in South American societies inspired by African traditions. Despite this diversity, there are unifying artistic themes present when considering the totality of the visual culture from the continent of Africa.

A caryatid is a sculpted female figure serving as an architectural support taking the place of a column or a pillar supporting an entablature on her head. The Greek term karyatides literally means "maidens of Karyai", an ancient town on the Peloponnese. Karyai had a temple dedicated to the goddess Artemis in her aspect of Artemis Karyatis: "As Karyatis she rejoiced in the dances of the nut-tree village of Karyai, those Karyatides, who in their ecstatic round-dance carried on their heads baskets of live reeds, as if they were dancing plants".

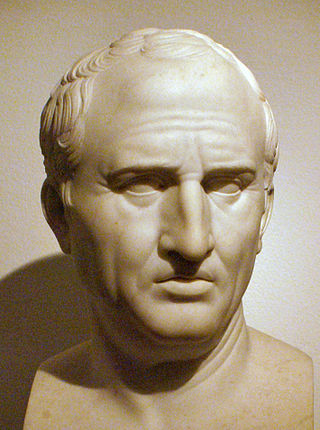

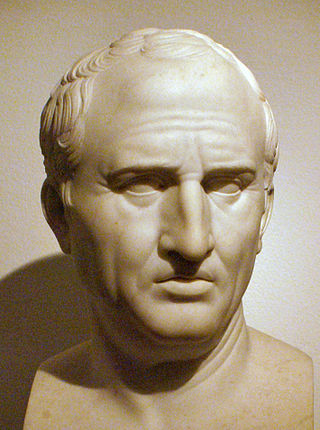

The method of loci is a strategy for memory enhancement, which uses visualizations of familiar spatial environments in order to enhance the recall of information. The method of loci is also known as the memory journey, memory palace, journey method, memory spaces, or mind palace technique. This method is a mnemonic device adopted in ancient Roman and Greek rhetorical treatises. Many memory contest champions report using this technique to recall faces, digits, and lists of words.

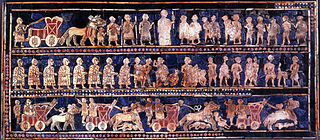

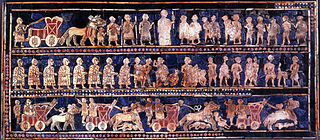

The Standard of Ur is a Sumerian artifact of the 3rd millennium BC that is now in the collection of the British Museum. It comprises a hollow wooden box measuring 21.59 centimetres (8.50 in) wide by 49.53 centimetres (19.50 in) long, inlaid with a mosaic of shell, red limestone and lapis lazuli. It comes from the ancient city of Ur. It dates to the First Dynasty of Ur during the Early Dynastic period and is around 4,600 years old. The standard was probably constructed in the form of a hollow wooden box with scenes of war and peace represented on each side through elaborately inlaid mosaics. Although interpreted as a standard by its discoverer, its original purpose remains enigmatic. It was found in a royal tomb in Ur in the 1920s next to the skeleton of a ritually sacrificed man who may have been its bearer.

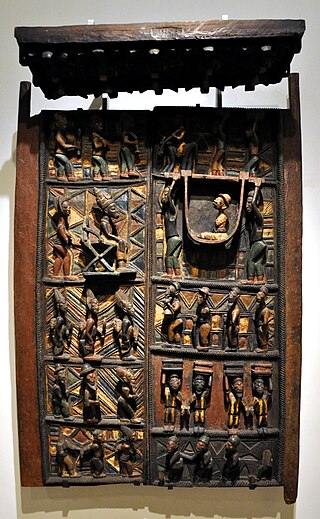

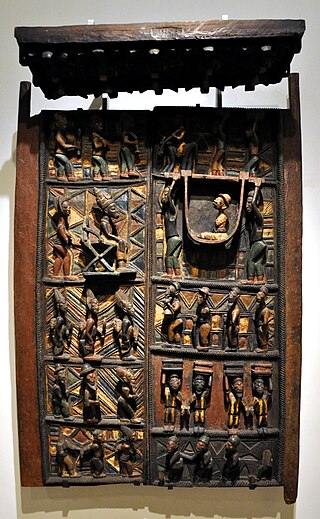

Olowe of Ise is considered by Western art historians and collectors to be one of the most important 20th century artists of the Yoruba people of what is today Nigeria, Africa. He was a wood sculptor and master innovator in the African style of design known as oju-ona.

The Luba people or Baluba are an ethno-linguistic group indigenous to the south-central region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The majority of them live in this country, residing mainly in Katanga, Kasai and Maniema. The Baluba Tribe consist of many sub-groups or clans who speak various dialects of Luba and other languages, such as Swahili.

Alison Saar is a Los Angeles, California based sculptor, mixed-media, and installation artist. Her artwork focuses on the African diaspora and black female identity and is influenced by African, Caribbean, and Latin American folk art and spirituality. Saar is well known for "transforming found objects to reflect themes of cultural and social identity, history, and religion."

Most African sculpture was historically in wood and other organic materials that have not survived from earlier than at most a few centuries ago; older pottery figures are found from a number of areas. Masks are important elements in the art of many peoples, along with human figures, often highly stylized. There is a vast variety of styles, often varying within the same context of origin depending on the use of the object, but wide regional trends are apparent; sculpture is most common among "groups of settled cultivators in the areas drained by the Niger and Congo rivers" in West Africa. Direct images of African deities are relatively infrequent, but masks in particular are or were often made for traditional African religious ceremonies; today many are made for tourists as "airport art". African masks were an influence on European Modernist art, which was inspired by their lack of concern for naturalistic depiction.

Benin art is the art from the Kingdom of Benin or Edo Empire (1440–1897), a pre-colonial African state located in what is now known as the Southern region of Nigeria. Primarily made of cast bronze and carved ivory, Benin art was produced mainly for the court of the Oba of Benin – a divine ruler for whom the craftsmen produced a range of ceremonially significant objects. The full complexity of these works can be appreciated through the awareness and consideration of two complementary cultural perceptions of the art of Benin: the Western appreciation of them primarily as works of art, and their understanding in Benin as historical documents and as mnemonic devices to reconstruct history, or as ritual objects. This original significance is of great importance in Benin.

The Songye people, sometimes written Songe, are a Bantu ethnic group from the central Democratic Republic of the Congo. They inhabit a vast territory between the Sankuru and Lubilash rivers in the west and the Lualaba River in the east. Many Songye villages can be found in present-day East Kasai province, parts of Katanga and Kivu Province. The people of Songye are divided into thirty-four conglomerate societies; each society is led by a single chief with a Judiciary Council of elders and nobles (bilolo). Smaller kingdoms east of the Lomami River refer to themselves as Songye, other kingdoms in the west, refer to themselves as Kalebwe, Eki, Ilande, Bala, Chofwe, Sanga and Tempa. As a society, the people of Songye are mainly known as a farming community; they do, however, take part in hunting and trading with other neighboring communities.

The Kingdom of Luba or Luba Empire (1585–1889) was a pre-colonial Central African state that arose in the marshy grasslands of the Upemba Depression in what is now southern Democratic Republic of Congo.

The Hemba people are a Bantu ethnic group in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

Benin ancestral altars are adorned with some of the finest examples of art from the Benin Kingdom of south-central Nigeria.

Lukasa, "the long hand", is a memory device that was created, manipulated and protected by the Bambudye, a once powerful secret society of the Luba. Lukasa are examples of Luba art.

Kuba art comprises a diverse array of media, much of which was created for the courts of chiefs and kings of the Kuba Kingdom. Such work often featured decorations, incorporating cowrie shells and animal skins as symbols of wealth, prestige and power. Masks are also important to the Kuba. They are used both in the rituals of the court and in the initiation of boys into adulthood, as well as at funerals. The Kuba produce embroidered raffia textiles which in the past was made for adornment, woven currency, or as tributary goods for funerals and other seminal occasions. The wealth and power of the court system allowed the Kuba to develop a class of professional artisans who worked primarily for the courts but also produced objects of high quality for other individuals of high status.

The Senufo people who live along the Ivory Coast in Africa created the ceremonial drum. The drum represents various aspects of tradition and life for certain Senufo communities. The construction of the drum is particularly indicative of the roles of women within Senufo communities and how they are seen as "preservers of life" those that hold up the structure and spirituality which govern their world. In fact, of the four Senufo societies, which educate and govern the individual acts of people, the divination governing sandogo society is composed mostly of women. It is worth noting that Senufo culture is matrilineal and certain societal positions such as the artisans, are determined by matrilineal inheritance. While ruled by elder male leaders, one's place in society, as well as their position for the future, is determined by the lineage of the mother. The ceremonial drum owned and housed in the Art Institute of Chicago epitomizes Senufo culture, and it is through drum's embellished designs that viewers are exposed to core beliefs of the Senufo, particularly, in how women are seen as guardians of divinity and supporting foundations of society for the Senufo.

The people who currently identify themselves as Basimba or BaShimba for many and Musimba or MuShimba for singular are a Bantu speaking community in Uganda. Before the 13th century they maintained a shared identity as Basimba, also defined in Swahili as "big lion," associated with either these people or the place which they came from.

Ngongo ya Chintu, known as the Master of Buli, was a sculptor of Luba art in what is today the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Little is known of his life, but his work has been collected internationally, and he was said to be well respected in his home village.

Susan Mullin Vogel is a curator, professor, scholar, and filmmaker whose area of focus is African art. She was a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, founded what is now The Africa Center in the early 1980s, served as Director of the Yale University Art Gallery, taught African art and architecture at Columbia University, and has made films.