The Lupeni strike of 1929 took place on 5 and 6 August 1929 in the mining town of Lupeni, in the Jiu Valley of Transylvania, Romania.

The Lupeni strike of 1929 took place on 5 and 6 August 1929 in the mining town of Lupeni, in the Jiu Valley of Transylvania, Romania.

Near the end of 1928, miners' leaders in the Jiu Valley had begun agitating for an extension of their collective work contract. Their demands included (in conformity with new legislation adopted under international pressure) an eight-hour workday, a 40% raise for those who worked at furnaces and in pits, the provision of food and boots, and an end to children working underground. The two sides could not reach an agreement. A trial ensued, and as the ruling of a court in Deva was not to the miners' liking, they appealed to the High Court of Cassation and Justice.

Also during 1928, the Lupeni miners had organised themselves into an independent union, led by Teodor Munteanu and a certain Moldoveanu. The union was not communist. Its leaders were closely aligned with the National Peasants' Party (PNȚ), which wished to strengthen its relations with workers. (After the strike, the opposition press asserted that the union had very close links with the PNȚ and that its members had taken part in a large electoral demonstration in Alba Iulia in May 1928.) During the first months of labour agitation, the union asked members to await the high court's ruling. However, communist agitators were active in the spring of 1929 in the Jiu Valley, [1] and the workers grew increasingly desperate as their conditions failed to improve and the court's ruling was delayed.

On the morning of 5 August, following a decision by the mine owners not to allow the union to pay each employee a days' wages from its own funds, some 200 workers met and decided to strike. About 3,000 men from the Elena and Victoria mines went on strike, going together to the Carolina and Ștefan mines. The situation quickly spun out of control, and the union leaders told the Deva authorities that they were no longer responsible for their members' actions.

The strikers then decided to occupy the power station controlling the mines' pumping machinery. A radical group went inside, forcing the men there to stop their work, endangering the lives of 200 miners still underground (who had refused to join the strike) and causing a power outage for the entire Jiu Valley. The engineer Radu Nicolau, the power station's manager, told to leave his station, was stabbed when he refused and had to be hospitalised. The other power station employees were forcibly evicted and the guard beaten.

Some authors see these actions as having had an air of sabotage, thus considering it very likely that communist agitators played an important role in radicalising the miners. [1] The local authorities took no action on the first day; indeed there were just 18 gendarmes in the vicinity.

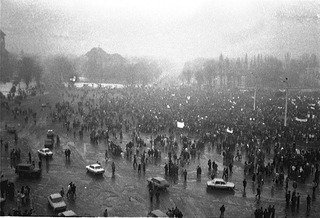

On the morning of 6 August, the leading authorities of Hunedoara County came to Lupeni, accompanied by 80 troops from the 4th frontier guards regiment and some 20 gendarmes. The mining company attempted to start the power station with strike-breakers in order to prevent the mines from being flooded and those underground from being asphyxiated, [2] but the strikers maintained a cordon around the works. (A prosecutor later reported that the men inside the power station were "armed with stakes, iron bars, bludgeons and revolvers and were awaiting the authorities with aggressive poses".) The public prosecutor made a final demand that the strikers withdraw from the power station; the strikers replied with a howl of defiance. Some 40 gendarmes now present advanced, trying to intimidate the strikers. According to later testimony, the workers then threw objects toward the gendarmes, wounding those in the first line. [3] When a striker fired a revolver, the 80 troops fired warning shots into the air. As the miners' aggressiveness was undiminished, the troops fired 78 bullets into the crowd (without orders, as established by an enquiry), some lodging in the power station's chimney. When the firing ceased, dozens of men lay on the ground; the rest, panic-stricken, fled quickly. Work at the station resumed immediately; troops and gendarmes guarded the station and all mine buildings.

Different sources give different numbers of dead and wounded: 16 dead and 200 wounded; [2] 22 dead and 58 wounded; [4] 30 dead and over a hundred wounded; [5] 32 dead and 56 wounded; [6] 40 dead (including two troops); [7] 58 dead and hundreds wounded. [8]

A more detailed report states that 13 miners died instantly and seven more in the following hours, with 23 hospitalized and seriously wounded. 30 were recorded with light wounds, but others went home undetected. 15 gendarmes were wounded and 10 soldiers, one seriously (knifed in the neck). The chief mechanic at the power station died of his wounds in hospital. Some 40 miners were arrested. On 9 August, the 20 miners (or 22 [9] ) were buried under tight security, with only their closest relatives allowed to be present; the graves were closely guarded for a time so as to prevent new disturbances. Three miners died in the following days. The government paid the families of those who had been shot. [3]

After the strike was repressed, various motives were ascribed to it. At the time, the National Peasants' Party (PNȚ) was in power; D.R. Ioanițescu, President of the Chamber of Deputies, blamed the extreme poverty of the underpaid workers and "possibly" Hungarian propagandists. (A majority of the dead were ethnic Hungarians.) Another member of the government blamed the mine directors; he alleged that the repeated refusals of the bosses to yield to the workers' demands and their dismissive assertions that they were led on by provocateurs of the banned Romanian Communist Party had driven them to desperation. Notably, this was not an isolated incident; nineteen strikes had taken place in the Valley between 1924 and 1928.

The Social Democrats, allies of the government, mainly blamed the mine directors but also charged that Communist agitators had misled the workers.

The mines belonged to a group of bankers from the National Liberal Party (the Peasants' bitter rivals), and one of their owners was Gheorghe Tătărescu, a minister in the previous government.

The following commentary appeared in the right-wing newspaper Universul just after the strike: "The troops only did their duty. The fault does not lie with them. They fired. It's a good thing they did so and it's good for people to know that they will fire whenever they receive orders to do so". Later, the chief military and civilian figures responsible for the shooting were removed from their positions as the press came to accept the fact that the strike dealt with poor conditions and was not a communist-led anti-regime action. As early as 9 August, the left-leaning Adevărul wrote: "What happened at Lupeni is a warning for our leaders, who for ten years have divided the country and ruined her economically, everywhere spreading misery, the mother of desperate mass actions".

D.I. Răducanu, the Minister of Labour, went to the Jiu Valley to investigate, and even Nicolae Lupu, a prominent PNȚ politician, pleaded the workers' cause in Parliament. Still, the fear of communist control of the strike had not been unjustified: working conditions in the mines had not been widely reported on before the strike, and Romanian-Soviet relations were quite strained, with the USSR having been involved in the Tatarbunary Uprising five years earlier. In the fall of 1929, because of the anti-strike measures taken, the Comintern branded Prime Minister Iuliu Maniu's government as "fascist".

In the fall of 1929, Panait Istrati, an author and communist sympathiser, wrote, "What happened at Lupeni was not the quelling of a revolt but a hunt for people. The authorities drank till daybreak and gave drink to the soldiers. A drunken prefect fired the first shot after the alarm was sounded. The miners were surrounded and slaughtered, without being given the opportunity to flee; then, when they managed to flee, the frontier guards ran after them, drunk with wine and blood".

The strike was glorified by the Communist regime as a symbol of the struggle of labour against capitalism. Although the communists' overall role had been small, [10] the regime claimed that the PCR had taken a leading role in it. The history textbook, edited by Mihail Roller, makes no mention of the independent union and claims that the PCR started the strike. It portrays the local authorities as assassins, alleging that the county prefect fired the first shot into a worker's chest. In 1948, Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej (who led Romania until 1965) said, "The calling of the Romanian communists penetrated the miners' ranks and showed them the path to the struggle".

The event featured in statues and songs, and Miners' Day was celebrated until 1989 on the first Sunday in August. Additionally, it was portrayed in an award-winning 1962 film ( Lupeni 29 ) starring Lica Gheorghiu , the daughter of Gheorgiu-Dej (and conceived with her in mind). The film, inspired by The Battleship Potemkin , portrayed the event as part of the class struggle and was also directed against the then-disgraced underground party activists; the role of the traitor Lucan was based on Vasile Luca (who participated in the preparations for the strike), fictionalised as the embodiment of human abjectness. [11]

During the Jiu Valley miners' strike of 1977, which started at Lupeni, strikers shouted "Lupeni '29! Lupeni '29!" in an effort to add legitimacy to their cause. [12] [13] As late as 1999, the strike still featured in Romanian political discourse, when a press release of the Ministry of Defense (then in the hands of anti-communists), in response to ex-communist former President Ion Iliescu's commemoration of the strike, described it as "a deliberate provocation of the Comintern, which evidently wished to destabilise the Romanian state" and asserted that the army's "energetic intervention" at the time "re-established peace and the rule of law". [14] [15]

The Western Federation of Miners (WFM) was a labor union that gained a reputation for militancy in the mines of the western United States and British Columbia. Its efforts to organize both hard rock miners and smelter workers brought it into sharp conflicts – and often pitched battles – with both employers and governmental authorities. One of the most dramatic of these struggles occurred in the Cripple Creek district of Colorado in 1903–1904; the conflicts were thus dubbed the Colorado Labor Wars. The WFM also played a key role in the founding of the Industrial Workers of the World in 1905 but left that organization several years later.

The mineriads were a series of protests and often violent altercations by Jiu Valley miners in Bucharest during the 1990s, particularly 1990–91. The term "mineriad" is also used to refer to the most significant and violent of these encounters, which occurred June 13–15, 1990. During the 1990s, the Jiu Valley miners played a visible role in Romanian politics, and their protests reflected inter-political and societal struggles after the Romanian Revolution.

Petroșani is a city in Hunedoara County, Transylvania, Romania, with a population of 31,044 (2021). The city has been associated with mining since the 19th century.

Lupeni is a mining city in the Jiu Valley in Hunedoara County, Romania, in the historical region of Transylvania. It is one of the oldest and largest cities in the Jiu Valley. It is located on the banks of the Western Jiu River within the Jiu Valley, at a height varying between 630 metres (2,070 ft) and 760 metres (2,490 ft). The distance from Lupeni to Petroșani is 18 kilometres (11 mi) on the DN66A road, and to Deva it is 114 km (71 mi).

The Jiu Valley is a region in southwestern Transylvania, Romania, in Hunedoara county, situated in a valley of the Jiu River between the Retezat Mountains and the Parâng Mountains. The region was heavily industrialised and the main activity was coal mining, but due to low efficiency, most of the mines were closed down in the years following the collapse of Communism in Romania. For a long time the place was called Romania's biggest coalfield.

Miron Cozma is a former Romanian labor-union organizer and politician, and leader of Romania's Jiu Valley coal miners' union. He is best known for his leading the miners of the Jiu Valley during the September 1991 Mineriad which overthrew the reformist Petre Roman government. Cozma was a controversial character in the 1990s, both within and outside of Jiu Valley.

In the Lattimer massacre at least 19 unarmed striking immigrant anthracite miners were killed violently at the Lattimer mine near Hazleton, Pennsylvania, United States, on September 10, 1897. The miners, mostly of Polish, Slovak, Lithuanian and German ethnicity, were shot and killed by a Luzerne County sheriff's posse. Scores more workers were wounded. The massacre was a turning point in the history of the United Mine Workers (UMW).

The Harlan County War, or Bloody Harlan, was a series of coal industry skirmishes, executions, bombings and strikes that took place in Harlan County, Kentucky, during the 1930s. The incidents involved coal miners and union organizers on one side and coal firms and law enforcement officials on the other. The Harlan County coal miners campaigned and fought to organize their workplaces and better their wages and working conditions. It was a nearly decade-long conflict, lasting from 1931 to 1939. Before its conclusion, an unknown number of miners, deputies and bosses would be killed, state and federal troops would occupy the county more than half a dozen times, two acclaimed folk singers would emerge, union membership would oscillate wildly and workers in the nation's most anti-labor coal county would ultimately be represented by a union.

The June 1990 Mineriad was the suppression of anti-National Salvation Front (FSN) rioting in Bucharest, Romania by the physical intervention of groups of industrial workers as well as coal miners from the Jiu Valley, brought to Bucharest by the government to counter the rising violence of the protesters. This event occurred several weeks after the FSN achieved a landslide victory in the May 1990 general election, the first elections after the fall of the communist regime of Nicolae Ceaușescu. Many of the miners, factory workers, and other anti-protester groups, fought with the protesters and bystanders. The violence resulted in some deaths and many injuries on both sides of the confrontations. Official figures listed seven fatalities and hundreds of injured, although media estimates of the number killed and injured varied widely and were often much higher.

The Miners Union League of the Jiu Valley represents the miners of the Jiu Valley.

The Jiu Valley miners' strike of 1977 was the largest protest movement against the Communist regime in Romania before its final days. It took place 1–3 August 1977 and was centered in the coal mining town of Lupeni, in Transylvania's Jiu Valley.

The 1877 Shamokin uprising occurred in Shamokin, Pennsylvania, in July 1877, as one of the several cities in the state where strikes occurred as part of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. The Great Strike was the first in the United States in which workers across the country united in an action against major companies. In many cities, the railroad workers were joined by other industrial workers in general strikes.

The 1892 Coeur d'Alene labor strike erupted in violence when labor union miners discovered they had been infiltrated by a Pinkerton agent who had routinely provided union information to the mine owners. The response to the labor violence, disastrous for the local miners' union, became the primary motivation for the formation of the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) the following year. The incident marked the first violent confrontation between the workers of the mines and their owners. Labor unrest continued after the 1892 strike, and surfaced again in the labor confrontation of 1899.

Lupeni Coal Mine is an underground mining exploitation, one of the largest in Romania located in Lupeni, one of six cities in the Jiu Valley region of Hunedoara County. The legal entity managing the Lupeni mine is the National Hard Coal Company which was set up in 1998. The mine has reserves of 65 million tonnes of coal.

Bărbăteni Coal Mine is an underground mining exploitation, one of the largest in Romania located in Lupeni, one of six cities in the Jiu Valley region of Hunedoara County. The legal entity managing the Bărbăteni mine is the National Hard Coal Company which was set up in 1998. The mine has reserves of 27.9 million tonnes of coal.

Anti-union violence is physical force intended to harm union officials, union organizers, union members, union sympathizers, or their families. It is most commonly used either during union organizing efforts, or during strikes. The aim most often is to prevent a union from forming, to destroy an existing union, or to reduce the effectiveness of a union or a particular strike action. If strikers prevent people or goods to enter or leave a workplace, violence may be used to allow people and goods to pass the picket line.

The Marikana massacre was the killing of thirty-four miners by the South African Police Service (SAPS) on 16 August 2012 during a six-week wildcat strike at the Lonmin platinum mine at Marikana near Rustenburg in South Africa's North West province. The massacre constituted the most lethal use of force by South African security forces against civilians since the Soweto uprising in 1976 and has been compared to the 1960 Sharpeville massacre.

September 1991 Mineriad was a political action and physical confrontation between the miners of the Jiu Valley and the Romanian authorities, that led to the resignation of Prime Minister Petre Roman's government. Led by Miron Cozma, president of the Jiu Valley Coal Miners Union, the miners engaged in a series of actions beginning in the 1990s referred to as "mineriads" whereby large numbers of miners traveled to the Romanian capital of Bucharest and engaged in demonstrations and sometimes violent confrontations against counter-demonstrators and government authorities.

Dissent in Romania under Nicolae Ceaușescu describes the voicing of disagreements with the government policies of Communist Romania during the totalitarian rule of Nicolae Ceaușescu after the July Theses in 1971. Because of Ceaușescu's extensive secret police and harsh punishments, open dissent was rare. Notable acts of dissent include Paul Goma's 1977 letters to Ceaușescu, the founding of SLOMR in 1979 and a number of work conflicts, such as the Jiu Valley miners' strike of 1977 and the Braşov Rebellion of 1987.

Anti-union violence in the United States is physical force intended to harm union officials, union organizers, union members, union sympathizers, or their families. It has most commonly been used either during union organizing efforts, or during strikes. The aim most often is to prevent a union from forming, to destroy an existing union, or to reduce the effectiveness of a union or a particular strike action. If strikers prevent people or goods to enter or leave a workplace, violence may be used to allow people and goods to pass the picket line.