A bain-marie, a type of heated bath, is a piece of equipment used in science, industry, and cooking to heat materials gently or to keep materials warm over a period of time. A bain-marie is also used to melt ingredients for cooking.

Distillation, or classical distillation, is the process of separating the components or substances from a liquid mixture by using selective boiling and condensation. Dry distillation is the heating of solid materials to produce gaseous products. Dry distillation may involve chemical changes such as destructive distillation or cracking and is not discussed under this article. Distillation may result in essentially complete separation, or it may be a partial separation that increases the concentration of selected components in the mixture. In either case, the process exploits differences in the relative volatility of the mixture's components. In industrial applications, distillation is a unit operation of practically universal importance, but it is a physical separation process, not a chemical reaction.

Sodium silicate is a generic name for chemical compounds with the formula Na

2xSi

yO

2y+x or (Na

2O)

x·(SiO

2)

y, such as sodium metasilicate Na

2SiO

3, sodium orthosilicate Na

4SiO

4, and sodium pyrosilicate Na

6Si

2O

7. The anions are often polymeric. These compounds are generally colorless transparent solids or white powders, and soluble in water in various amounts.

Plaster is a building material used for the protective or decorative coating of walls and ceilings and for moulding and casting decorative elements. In English, "plaster" usually means a material used for the interiors of buildings, while "render" commonly refers to external applications. Another imprecise term used for the material is stucco, which is also often used for plasterwork that is worked in some way to produce relief decoration, rather than flat surfaces.

A pot still is a type of distillation apparatus or still used to distill flavoured liquors such as whisky or cognac, but not rectified spirit because they are bad at separating congeners. Pot stills operate on a batch distillation basis. Traditionally constructed from copper, pot stills are made in a range of shapes and sizes depending on the quantity and style of spirit desired.

Sublimation is the transition of a substance directly from the solid to the gas state, without passing through the liquid state. Sublimation is an endothermic process that occurs at temperatures and pressures below a substance's triple point in its phase diagram, which corresponds to the lowest pressure at which the substance can exist as a liquid. The reverse process of sublimation is deposition or desublimation, in which a substance passes directly from a gas to a solid phase. Sublimation has also been used as a generic term to describe a solid-to-gas transition (sublimation) followed by a gas-to-solid transition (deposition). While vaporization from liquid to gas occurs as evaporation from the surface if it occurs below the boiling point of the liquid, and as boiling with formation of bubbles in the interior of the liquid if it occurs at the boiling point, there is no such distinction for the solid-to-gas transition which always occurs as sublimation from the surface.

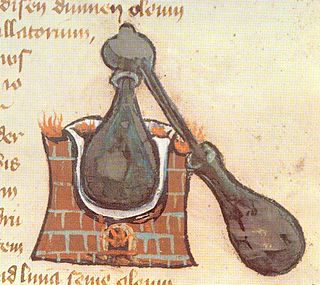

An alembic is an alchemical still consisting of two vessels connected by a tube, used for distillation of liquids.

In a chemistry laboratory, a retort is a device used for distillation or dry distillation of substances. It consists of a spherical vessel with a long downward-pointing neck. The liquid to be distilled is placed in the vessel and heated. The neck acts as a condenser, allowing the vapors to condense and flow along the neck to a collection vessel placed underneath.

In vacuum applications, a cold trap is a device that condenses all vapors except the permanent gases into a liquid or solid. The most common objective is to prevent vapors being evacuated from an experiment from entering a vacuum pump where they would condense and contaminate it. Particularly large cold traps are necessary when removing large amounts of liquid as in freeze drying.

Lime is a calcium-containing inorganic mineral composed primarily of oxides, and hydroxide, usually calcium oxide and/ or calcium hydroxide. It is also the name for calcium oxide which occurs as a product of coal-seam fires and in altered limestone xenoliths in volcanic ejecta. The word lime originates with its earliest use as building mortar and has the sense of sticking or adhering.

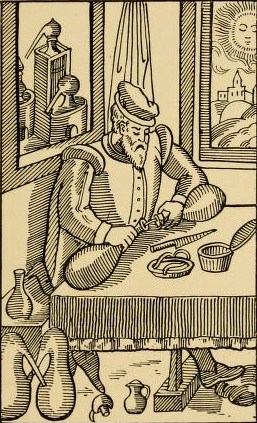

Mary or Maria the Jewess, also known as Mary the Prophetess, is an early alchemist who is known from the works of the Gnostic Christian writer Zosimos of Panopolis. On the basis of Zosimos's comments, she lived between the first and third centuries A.D. in Alexandria. French, Taylor and Lippmann list her as one of the first alchemical writers, dating her works at no later than the first century.

Egyptian faience is a sintered-quartz ceramic material from Ancient Egypt. The sintering process "covered [the material] with a true vitreous coating" as the quartz underwent vitrification, creating a bright lustre of various colours "usually in a transparent blue or green isotropic glass". Its name in the Ancient Egyptian language was tjehenet, and modern archeological terms for it include sintered quartz, glazed frit, and glazed composition. Tjehenet is distinct from the crystalline pigment Egyptian blue, for which it has sometimes incorrectly been used as a synonym.

Cement clinker is a solid material produced in the manufacture of Portland cement as an intermediary product. Clinker occurs as lumps or nodules, usually 3 millimetres (0.12 in) to 25 millimetres (0.98 in) in diameter. It is produced by sintering limestone and aluminosilicate materials such as clay during the cement kiln stage.

The Queries is the third book to English physicist Isaac Newton's Opticks, with various numbers of Query sections or "question" sections, expanded on from 1704 to 1718, that contains Newton's final thoughts on the future puzzles of science. Query 31, in particular, launched affinity chemistry and the dozens of affinity tables that were made in the 18th century, based on Newton's description of affinity gradients.

Diana's Tree, also known as the Philosopher's Tree, was considered a precursor to the Philosopher’s Stone and resembled coral in regards to its structure. It is a dendritic amalgam of crystallized silver, obtained from mercury in a solution of silver nitrate; so-called by the alchemists, among whom "Diana" stood for silver. The arborescence of this amalgam, which even included fruit-like forms on its branches, led pre-modern chemical philosophers to theorize the existence of life in the kingdom of minerals.

Glass casting is the process in which glass objects are cast by directing molten glass into a mould where it solidifies. The technique has been used since the Egyptian period. Modern cast glass is formed by a variety of processes such as kiln casting, or casting into sand, graphite or metal moulds.

Gold parting is the separating of gold from silver. Gold and silver are often extracted from the same ores and are chemically similar and therefore hard to separate. Over the centuries special means of separation have been invented.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to alchemy:

Waidan, translated as external alchemy or external elixir, is the early branch of Chinese alchemy that focuses upon compounding elixirs of immortality by heating minerals, metals, and other natural substances in a luted crucible. The later branch of esoteric neidan "inner alchemy", which borrowed doctrines and vocabulary from exoteric waidan, is based on allegorically producing elixirs within the practitioner's body, through Daoist meditation, diet, and physiological practices. The practice of waidan external alchemy originated in the early Han dynasty, grew in popularity until the Tang (618–907) when neidan began and several emperors died from alchemical elixir poisoning, and gradually declined until the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).