Wittenberg, is the fourth-largest town in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. Wittenberg is situated on the River Elbe, 60 kilometers (37 mi) north of Leipzig and 90 kilometers (56 mi) south-west of Berlin, and has a population of 46,008 (2018).

Eisenach is a town in Thuringia, Germany with 42,000 inhabitants, located 50 kilometres west of Erfurt, 70 km southeast of Kassel and 150 km northeast of Frankfurt. It is the main urban centre of western Thuringia and bordering northeastern Hessian regions, situated near the former Inner German border. A major attraction is Wartburg castle, which has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1999.

The Wartburg is a castle originally built in the Middle Ages. It is situated on a precipice of 410 meters (1,350 ft) to the southwest of and overlooking the town of Eisenach, in the state of Thuringia, Germany. It was the home of St. Elisabeth of Hungary, the place where Martin Luther translated the New Testament of the Bible into German, the site of the Wartburg festival of 1817 and the supposed setting for the possibly legendary Sängerkrieg. It was an important inspiration for Ludwig II when he decided to build Neuschwanstein Castle.

"A Mighty Fortress Is Our God" is one of the best known hymns by the Protestant Reformer Martin Luther, a prolific hymnwriter. Luther wrote the words and composed the hymn tune between 1527 and 1529. It has been translated into English at least seventy times and also into many other languages. The words are mostly original, although the first line paraphrases that of Psalm 46.

Katharina von Bora, after her wedding Katharina Luther, also referred to as "die Lutherin", was the wife of the German reformer Martin Luther and a seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation. Although little is known about her, she is often considered to have been important to the Reformation, her marriage setting a precedent for Protestant family life and clerical marriage.

Johannes Bugenhagen, also called Doctor Pomeranus by Martin Luther, was a German theologian and Lutheran priest who introduced the Protestant Reformation in the Duchy of Pomerania and Denmark in the 16th century. Among his major accomplishments was organization of Lutheran churches in Northern Germany and Scandinavia. He has also been called the "Second Apostle of the North".

German Christians were a pressure group and a movement within the German Evangelical Church that existed between 1932 and 1945, aligned towards the antisemitic, racist and Führerprinzip ideological principles of Nazism with the goal to align German Protestantism as a whole towards those principles. Their advocacy of these principles led to a schism within 23 of the initially 28 regional church bodies (Landeskirchen) in Germany and the attendant foundation of the opposing Confessing Church in 1934. Theologians Karl Barth and Dietrich Bonhoeffer drafted the Barmen Declaration the same year opposing Nazi doctrines.

Justus Jonas, the Elder, or simply Justus Jonas, was a German Lutheran theologian and reformer. He was a Jurist, Professor and Hymn writer. He is best known for his translations of the writings of Martin Luther and Philipp Melanchthon. He accompanied Martin Luther in his final moments.

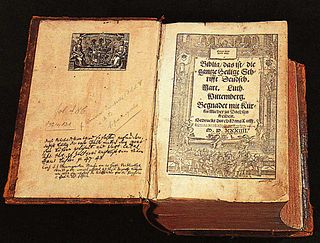

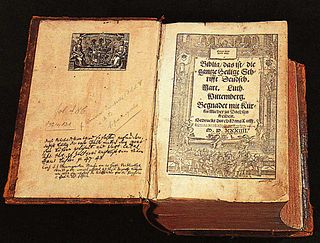

The Luther Bible is a German language Bible translation by the Protestant reformer Martin Luther. A New Testament translation by Luther was first published in September 1522, and the completed Bible, containing a translation of the Old and New Testaments with Apocrypha, in 1534. Luther continued to make improvements to the text until 1545. It was the first full translation of the Bible into German that used not only the Latin Vulgate but also the Greek.

Caspar Creuziger, also known as Caspar Cruciger the Elder, was a German Renaissance humanist and Protestant reformer. He was professor of Theology at the University of Wittenberg, preacher at the Castle Church, secretary to and worked with Martin Luther to revise Luther's German Bible translation.

Georg Rörer was a German Lutheran theologian, clergyman and Protestant reformer.

Martin Luther was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, professor, and Augustinian friar. He was the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation, and his theological beliefs form the basis of Lutheranism.

Georg Rhau (Rhaw) was a German publisher and composer. He was one of the most significant music printers in Germany in the first half of the 16th century, during the early period of the Protestant Reformation. He was principally active in Wittenberg, Saxony, the town where Martin Luther is said to have nailed the Ninety-five Theses to the door of the Castle Church, initiating the Reformation. Rhau's support as a printer was critical to Luther's success.

The Institute for the Study and Elimination of Jewish Influence on German Church Life was a cross-church establishment by eleven German Protestant churches in Nazi Germany, founded at the instigation of the German Christian movement. It was set up in Eisenach under Siegfried Leffler and Walter Grundmann. Georg Bertram, professor of New Testament at the University of Giessen, who led the Institute from 1943 until the Institute's dissolution in May 1945, wrote about its goals in March 1944: "'This war is Jewry's war against Europe.' This sentence contains a truth which is again and again confirmed by the research of the Institute. This research work is not only adjusted to the frontal attack, but also to the strengthening of the inner front for attack and defence against all the covert Jewry and Jewish being, which has oozed into the Occidental Culture in the course of centuries, ... thus the Institute, in addition to the study and elimination of the Jewish influence, also has the positive task of understanding the own Christian German being and the organisation of a pious German life based on this knowledge."

The Lutherhaus is a writer's house museum in Lutherstadt Wittenberg, Germany. Originally built in 1504 as part of the University of Wittenberg, the building was the home of Martin Luther for most of his adult life and a significant location in the history of the Protestant Reformation. Luther was living here when he wrote his 95 Theses.

Eisenach Charterhouse is a former charterhouse, or Carthusian monastery, in Eisenach in Thüringia, Germany, founded in 1378 and suppressed in 1525.

The 'Dejudaization Institute' Memorial is a memorial installation erected in Eisenach at the behest of eight Protestant regional churches. The memorial remembers the Protestant regional churches' culpability for the antisemitic Institute for the Study and Eradication of Jewish Influence on German Church Life they founded, which was active between 1939 and 1945 in the Nazi era. The memorial installation is intended to be understood as the Protestant churches' confession of guilt and as a memorial to the victims of the church's anti-Judaism and antisemitism. It was unveiled on May 6, 2019, eighty years after the founding of the "Dejudaization Institute".

Diego Lasansky is an American artist whose focus is on printmaking, painting, and drawing. He lives in Iowa City, Iowa.

A Lutherstadt is a city German protestant reformer Martin Luther visited or played an important role. Two cities, Lutherstadt Eisleben and Lutherstadt Wittenberg, have "Lutherstadt" in their official names, while Mansfeld-Lutherstadt is the unofficial name of a district in Mansfeld. These three places which were important in Luther's life were awarded the "European Heritage Label".

Man in a cube is a contemporary sculpture created by Chinese artist Ai Weiwei in 2017 for the exhibition Luther and the Avant-Garde marking the quincentenary of the Reformation. It has been on permanent display in the courtyard of Lutherhaus Eisenach since October 2020.