Canopic jars are containers that were used by the ancient Egyptians during the mummification process, to store and preserve the viscera of their owner for the afterlife. They were commonly either carved from limestone, or were made of pottery. These jars were used by the ancient Egyptians from the time of the Old Kingdom, until the time of the Late Period or the Ptolemaic Period, by which time the viscera were simply wrapped and placed with the body. The viscera were not kept in a single canopic jar: each jar was reserved for specific organs. The term canopic reflects the mistaken association by early Egyptologists with the Greek legend of Canopus – the boat captain of Menelaus on the voyage to Troy – "who was buried at Canopus in the Delta where he was worshipped in the form of a jar". In alternative versions, the name derives from the location Canopus in the western Nile Delta near Alexandria, where human-headed jars were worshipped as personifications of the god Osiris.

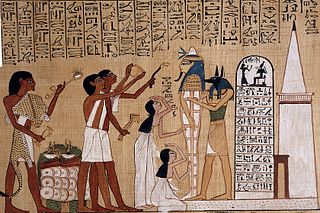

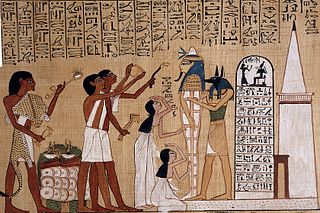

The ancient Egyptians had an elaborate set of funerary practices that they believed were necessary to ensure their immortality after death. These rituals included mummifying the body, casting magic spells, and burials with specific grave goods thought to be needed in the afterlife.

Tomb KV60 is an ancient Egyptian tomb in the Valley of the Kings, Egypt. It was discovered by Howard Carter in 1903, and re-excavated by Donald P. Ryan in 1989. It is one of the more perplexing tombs of the Theban Necropolis, due to the uncertainty over the identity of one female mummy found there (KV60A). She is identified by some, such as Egyptologist Elizabeth Thomas, to be that of the Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh Hatshepsut; this identification is advocated for by Zahi Hawass.

Tomb KV42 is an ancient Egyptian tomb located in the Valley of the Kings in Egypt. It was constructed for Hatshepsut-Meryetre, the wife of Thutmose III, but she was not buried in the tomb. It was reused by Sennefer, a mayor of Thebes during the reign of Amenhotep II, and by several members of his family. The tomb has a cartouche-shaped burial chamber, like other early Eighteenth Dynasty tombs.

Tomb KV35 is the tomb of Pharaoh Amenhotep II located in the Valley of the Kings in Luxor, Egypt. Later, it was used as a cache for other royal mummies. It was discovered by Victor Loret in March 1898.

The necropolis of Draʻ Abu el-Naga' is located on the West Bank of the Nile at Thebes, Egypt, just by the entrance of the dry bay that leads up to Deir el-Bahari and north of the necropolis of el-Assasif. The necropolis is located near the Valley of the Kings.

KV20 is a tomb in the Valley of the Kings (Egypt). It was probably the first royal tomb to be constructed in the valley. KV20 was the original burial place of Thutmose I and later was adapted by his daughter Hatshepsut to accommodate her and her father. The tomb was known to the Napoleonic expedition in 1799 and had been visited by several explorers between 1799 and 1903. A full clearance of the tomb was undertaken by Howard Carter in 1903–1904. KV20 is distinguishable from other tombs in the valley, both in its general layout and because of the atypical clockwise curvature of its corridors.

Tomb KV46 in the Valley of the Kings is the tomb of the ancient Egyptian noble Yuya and his wife Thuya, the parents of Queen Tiye and Anen. It was discovered in February 1905 by Chief Inspector of Antiquities James E. Quibell, excavating under the sponsorship of American millionaire Theodore M. Davis. Despite robberies in antiquity, the undecorated tomb preserved a great deal of its original contents including chests, beds, chairs, a chariot, and numerous storage jars. Additionally, the riffled but undamaged mummies of Yuya and Thuya were found within their disturbed coffin sets. Prior to the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun, this was considered to be one of the greatest discoveries in Egyptology.

Tomb KV36, located in the Valley of the Kings in Egypt, was used for the burial of the noble Maiherpri from the Eighteenth Dynasty.

KV63 is a recently opened chamber in Egypt's Valley of the Kings pharaonic necropolis. Initially believed to be a royal tomb, it is now believed to have been a storage chamber for the mummification process. It was found in 2005 by a team of archaeologists led by Dr. Otto Schaden.

This is a glossary of ancient Egypt artifacts.

Theban Tomb 8, abbreviated TT8, is the funerary chapel and tomb of the ancient Egyptian foreman Kha and his wife, Merit. They are known for their undisturbed tomb discovered in 1906 which is considered the best preserved non-royal burial in Egypt. Kha was an "overseer of works" at Deir el-Medina in the mid-Eighteenth Dynasty, where he was responsible for royal tombs constructed in the reigns of pharaohs Amenhotep II, Thutmose IV and Amenhotep III. Of unknown background, he rose to his position through skill and was ultimately rewarded for his work by at least one king. He and his wife Merit had three known children, one of whom also worked in the royal necropolis. Kha died in his 50s or 60s, while Merit died, seemingly unexpectedly, in her 30s.

Menhet, Menwi and Merti, also spelled Manhata, Manuwai and Maruta, were three minor foreign-born wives of Pharaoh Thutmose III of the Eighteenth Dynasty. They are known for their lavishly furnished rock-cut tomb in Wady Gabbanat el-Qurud near Luxor, Egypt. They are suggested to be Syrian, as the names all fit into Canaanite name forms, although their ultimate origin is unknown. A West Semitic origin is likely, but both West Semitic and Hurrian derivations have been suggested for Menwi. Each of the wives bear the title of "king's wife", and were likely only minor members of the royal harem. It is not known if the women were related as the faces on the lids of their canopic jars are all different.

Ramose was the father and Hatnofer the mother of Senenmut, one of the most important state officials under the reign of the Egyptian queen Hatshepsut in the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. The commoner origins of Ramose and the rise of his son Senenmut were long considered to be prime examples of high social mobility in New Kingdom Egypt. For instance, almost nothing is known of Ramose's origins, but he seems to have been a man of modest means—anything from a tenant peasant or farmer, to an artisan or even a small landowner. When Ramose died he was a man aged 50–60. Hatnofer was an elderly lady, with grey or even white hair. They are believed to have been born at Armant, a town only ten miles (16 km) south of Thebes within Upper Egypt presumably during the reign of Ahmose I, the founder of Egypt's illustrious 18th dynasty.

Imhotep was the governor of the city, a judge and a vizier under Thutmose I. He was also said to be a tutor to the sons of the king.

Senebtisi was an ancient Egyptian woman who lived at the end of the 12th Dynasty, around 1800 BC. She is only known from her undisturbed burial found at Lisht.

Amenemhat was a Nubian official under Hatshepsut and Thutmosis III. He was chief of Teh-khet and was therefore a governor ruling a region in Lower Nubia for the Egyptian state. In the New Kingdom, Egyptian kings had conquered Lower Nubia. To secure control over the new region they appointed people of the local elite as governors. Teh-khet was a Nubian region that covered the area about Debeira and Serra. The local governors here formed a family, while the governor proper held the title chief of Teh-khet.

The Theban Tomb known as MMA 56 is located in Deir el-Bahari. It forms part of the Theban Necropolis, situated on the west bank of the Nile opposite Luxor. The tomb is the burial place of the ancient Egyptian Lady Ankhshepenwepet, also called Neb(et)-imauemhat, who dates to the 25th Dynasty. Ankhshepenwepet was a Singer in the Residence of Amun and an attendant of Shepenwepet I. It was excavated by Herbert E. Winlock on behalf of the Metropolitan Museum of Arts in 1923–24.

The Theban Tomb known as MMA 60 is located in Deir el-Bahari. It forms part of the Theban Necropolis, situated on the west bank of the Nile opposite Luxor. The tomb is the burial place several high ranking individuals dating to the 21st Dynasty.

The Theban Tomb TT414 is located in El-Assasif, part of the Theban Necropolis, on the west bank of the Nile, opposite to Luxor. The tomb was originally constructed in the El-Assasif necropolis for the use of Ankh-hor and his family. Ankhor was the Chief Steward to the God's Wife Nitocris during the 26th Dynasty. Ankh-hor is dated to the reigns of Pharaohs Psamtik II and Apries. The tomb was later usurped during the 30th Dynasty and the Ptolemaic Period.