Related Research Articles

The Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) is an agreement, among all of the 27 member states of the European Union, to facilitate and maintain the stability of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). Based primarily on Articles 121 and 126 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, it consists of fiscal monitoring of members by the European Commission and the Council of the European Union, and the issuing of a yearly recommendation for policy actions to ensure a full compliance with the SGP also in the medium-term. If a Member State breaches the SGP's outlined maximum limit for government deficit and debt, the surveillance and request for corrective action will intensify through the declaration of an Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP); and if these corrective actions continue to remain absent after multiple warnings, the Member State can ultimately be issued economic sanctions. The pact was outlined by a resolution and two council regulations in July 1997. The first regulation "on the strengthening of the surveillance of budgetary positions and the surveillance and coordination of economic policies", known as the "preventive arm", entered into force 1 July 1998. The second regulation "on speeding up and clarifying the implementation of the excessive deficit procedure", known as the "dissuasive arm", entered into force 1 January 1999.

The budget of the European Union is used to finance EU funding programmes and other expenditure at the European level.

Government procurement or public procurement is undertaken by the public authorities of the European Union (EU) and its member states in order to award contracts for public works and for the purchase of goods and services in accordance with principles derived from the Treaties of the European Union. Such procurement represents 14% of EU GDP as of 2017, and has been the subject of increasing European regulation since the 1970s because of its importance to the European single market.

The Competitiveness and Innovation Framework Programme (CIP) of the European Commission is meant to improve the competitiveness of European companies facing the challenges of globalization. The programme is mainly aimed at small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which will receive support for innovation activities, better access to finance and business support services. It will run from 2007 to 2013.

The Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications (BEREC) is the body in which the regulators of the telecommunications markets in the European Union work together. Other participants are the representative of the European Commission, as well as telecommunication regulators from the member states of the EEA and of states that are in the process of joining the EU.

The European Citizens' Initiative (ECI) is a European Union (EU) mechanism aimed at increasing direct democracy by enabling "EU citizens to participate directly in the development of EU policies", introduced with the Treaty of Lisbon in 2007. The initiative enables one million citizens of the European Union, who are nationals of at least seven member states, to call directly on the European Commission to propose a legal act in an area where the member states have conferred powers onto the EU level. This right to request the commission to initiate a legislative proposal puts citizens on the same footing as the European Parliament and the European Council, who enjoy this right according to Articles 225 and 241 TFEU, respectively. The commission holds the right of initiative in the EU. The first registered ECI, Fraternité 2020, was initiated on 9 May 2012, although the first submitted ECI was One Single Tariff.

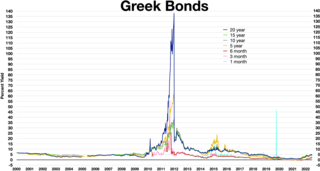

The European debt crisis, often also referred to as the eurozone crisis or the European sovereign debt crisis, is a multi-year debt crisis that took place in the European Union (EU) from 2009 until the mid to late 2010s. Several eurozone member states were unable to repay or refinance their government debt or to bail out over-indebted banks under their national supervision without the assistance of third parties like other eurozone countries, the European Central Bank (ECB), or the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The economic and monetary union (EMU) of the European Union is a group of policies aimed at converging the economies of member states of the European Union at three stages.

Europe 2020 is a 10-year strategy proposed by the European Commission on 3 March 2010 for advancement of the economy of the European Union. It aims at a "smart, sustainable, inclusive growth" with greater coordination of national and European policy. It follows the Lisbon Strategy for the period 2000–2010.

European Union–Pakistan relations are the international relations between the common foreign policy and trade relations of the European Union and the Islamic Republic of Pakistan.

Greece faced a sovereign debt crisis in the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2007–2008. Widely known in the country as The Crisis, it reached the populace as a series of sudden reforms and austerity measures that led to impoverishment and loss of income and property, as well as a small-scale humanitarian crisis. In all, the Greek economy suffered the longest recession of any advanced mixed economy to date. As a result, the Greek political system has been upended, social exclusion increased, and hundreds of thousands of well-educated Greeks have left the country.

The European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism (EFSM) is an emergency funding programme reliant upon funds raised on the financial markets and guaranteed by the European Commission using the budget of the European Union as collateral. It runs under the supervision of the Commission and aims at preserving financial stability in Europe by providing financial assistance to member states of the European Union in economic difficulty.

The European Stability Mechanism (ESM) is an intergovernmental organization located in Luxembourg City, which operates under public international law for all eurozone member states having ratified a special ESM intergovernmental treaty. It was established on 27 September 2012 as a permanent firewall for the eurozone, to safeguard and provide instant access to financial assistance programmes for member states of the eurozone in financial difficulty, with a maximum lending capacity of €500 billion. It has replaced two earlier temporary EU funding programmes: the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and the European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism (EFSM).

The Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union; also referred to as TSCG, or more plainly the Fiscal Stability Treaty is an intergovernmental treaty introduced as a new stricter version of the Stability and Growth Pact, signed on 2 March 2012 by all member states of the European Union (EU), except the Czech Republic and the United Kingdom. The treaty entered into force on 1 January 2013 for the 16 states which completed ratification prior to this date. As of 3 April 2019, it had been ratified and entered into force for all 25 signatories plus Croatia, which acceded to the EU in July 2013, and the Czech Republic.

The EU economic governance, Sixpack describes a set of European legislative measures to reform the Stability and Growth Pact and introduces greater macroeconomic surveillance, in response to the European debt crisis of 2009. These measures were bundled into a "six pack" of regulations, introduced in September 2010 in two versions respectively by the European Commission and a European Council task force. In March 2011, the ECOFIN council reached a preliminary agreement for the content of the Sixpack with the commission, and negotiations for endorsement by the European Parliament then started. Ultimately it entered into force 13 December 2011, after one year of preceding negotiations. The six regulations aim at strengthening the procedures to reduce public deficits and address macroeconomic imbalances.

The Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM) is one of the pillars of the European Union's banking union. The Single Resolution Mechanism entered into force on 19 August 2014 and is directly responsible for the resolution of the entities and groups directly supervised by the European Central Bank as well as other cross-border groups. The centralised decision making is built around the Single Resolution Board (SRB) consisting of a Chair, a Vice Chair, four permanent members, and the relevant national resolution authorities.

The Third Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece, usually referred to as the third bailout package or the third memorandum, is a memorandum of understanding on financial assistance to the Hellenic Republic in order to cope with the Greek government-debt crisis.

CMFB, in the context of European statistics, stands for Committee on Monetary, Financial and Balance of Payments Statistics. Originally established in 1991, the Committee is an advisory committee for the European Commission (Eurostat) and European Central Bank and a platform for cooperation between the statistical and central banking community in Europe.

The European Semester of the European Union was established in 2010 as an annual cycle of economic and fiscal policy coordination. It provides a central framework of processes within the EU socio-economic governance. The European Semester is a core component of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) and it annually aggregates different processes of control, surveillance and coordination of budgetary, fiscal, economic and social policies. It also offers a large space for discussions and interactions between the European institutions and Member States. As a recurrent cycle of budgetary cooperation among the EU Member States, it runs from November to June and is preceded in each country by a national semester running from July to October in which the recommendations introduced by the Commission and approved by the Council are to be adopted by national parliaments and construed into national legislation. The European Semester has evolved over the years with a gradual inclusion of social, economic, and employment objectives and it is governed by mainly three pillars which are a combination of hard and soft law due a mix of surveillance mechanisms and possible sanctions with coordination processes. The main objectives of the European Semester are noted as: contributing to ensuring convergence and stability in the EU; contributing to ensuring sound public finances; fostering economic growth; preventing excessive macroeconomic imbalances in the EU; and implementing the Europe 2020 strategy. However, the rate of the implementation of the recommendations adopted during the European Semester has been disappointing and has gradually declined since its initiation in 2011 which has led to an increase in the debate/criticism towards the effectiveness of the European Semester.

References

- 1 2 "Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure" . Retrieved 10 April 2013.

- 1 2 "MIP Scoreboard" . Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ↑ "The MIP framework" . Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ↑ "REGULATION (EU) No 1176/2011 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 16 November 2011: On the prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances". Official Journal of the European Union. 23 November 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 July 2014.

- 1 2 "Economic governance review: Report on the application of Regulations (EU) n° 1173/2011, 1174/2011, 1175/2011, 1176/2011, 1177/2011, 472/2013 and 473/2013" (PDF). European Commission. 28 November 2014.

- ↑ "Commission's first Alert Mechanism Report: tackling macroeconomic imbalances in the EU" . Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Following in-depth reviews, Commission calls on Member States to tackle macroeconomic imbalances" . Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ↑ "Second Alert Mechanism Report on macroeconomic imbalances in EU Member States" . Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "COM/2013/0199 – COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL AND TO THE EUROGROUP: Results of in-depth reviews under Regulation (EU) No 1176/2011 on the prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances". European Commission. 10 April 2013.

- ↑ "Commission concludes in-depth reviews of macroeconomic imbalances in 13 Member States" . Retrieved 10 April 2013.

- ↑ "Why the eurozone needs stronger institutions". Rabobank Economic Research Department. 22 August 2013.

- ↑ "Will Slovenia be next week's Brussels target?". Financial Times. 23 May 2013.

- 1 2 "Press Speaking Points at the European Semester Press Conference (SPEECH/13/481, 29/05/2013)". European Commission. 29 May 2013.

- 1 2 "Will the Alert Mechanism Report 2014 improve economic rebalancing?". Rabobank Economic Research Department. 15 November 2013.

- ↑ "Third Alert Mechanism Report on macroeconomic imbalances in EU Member States" . Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Results of in-depth reviews under Regulation (EU) No 1176/2011 on the prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances" (PDF). 5 March 2014.

- ↑ "Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure". European Commission. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- 1 2 "Speaking points by Vice-President Olli Rehn at the Press Conference on the Country Specific Recommendations (SPEECH/14/419, 02/06/2014)". European Commission. 2 June 2014.

- 1 2 3 "2015 European Semester: Assessment of growth challenges, prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances, and results of in-depth reviews under Regulation (EU) No 1176/2011" (PDF). European Commission. 26 February 2015.

- ↑ "2015 European Semester: Country-specific recommendations" (PDF). European Commission. 13 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "COM(2016) 95 final/2 – COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL AND TO THE EUROGROUP: 2016 European Semester: Assessment of progress on structural reforms, prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances, and results of in-depth reviews under Regulation (EU) No 1176/2011". European Commission. 8 March 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "COM(2017) 90 final – COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL AND TO THE EUROGROUP: 2017 European Semester: Assessment of progress on structural reforms, prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances, and results of in-depth reviews under Regulation (EU) No 1176/2011" (PDF). European Commission. 22 February 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL AND TO THE EUROGROUP: 2018 European Semester: Assessment of progress on structural reforms, prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances, and results of in-depth reviews under Regulation (EU) No 1176/2011". European Commission. 7 March 2018.

- 1 2 3 "COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL AND TO THE EUROGROUP: 2019 European Semester: Assessment of progress on structural reforms, prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances, and results of in-depth reviews under Regulation (EU) No 1176/2011". European Commission. 27 February 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL AND TO THE EUROGROUP: 2020 European Semester: Assessment of progress on structural reforms, prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances, and results of in-depth reviews under Regulation (EU) No 1176/2011". European Commission. 26 February 2020.

- 1 2 3 "COM(2021)500: Economic policy coordination in 2021: overcoming COVID-19, supporting the recovery and modernising our economy". European Commission. 2 June 2021.

- 1 2 3 "COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE, THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS AND THE EUROPEAN INVESTMENT BANK 2022 European Semester - Spring Package". European Commission. 23 May 2022.

- ↑ "MIP indicators through the years, in: The Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure (MIP) introduced". Eurostat. 26 March 2018.

- ↑ "Regulation (EU) No 1176/2011 on the prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances" . Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ↑ "Regulation (EU) No 1174/2011 on enforcement measures to correct excessive macroeconomic imbalances in the euro area" . Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ↑ "ECOFIN Council Conclusions on EU Statistics 2015". 8 December 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- 1 2 "Memorandum of Understanding on the Cooperation between the Members of the European Statistical System and the Members of the European System of Central Banks" (PDF). European Central Bank. 24 April 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- 1 2 "Memorandum of Understanding on the Cooperation between the Members of the European Statistical System and the Members of the European System of Central Banks". Eurostat. 24 April 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ "REGULATION (EC) No 223/2009 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 11 March 2009 on European statistics and repealing Regulation (EC, Euratom) No 1101/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the transmission of data subject to statistical confidentiality to the Statistical Office of the European Communities, Council Regulation (EC) No 322/97 on Community Statistics, and Council Decision 89/382/EEC, Euratom establishing a Committee on the Statistical Programmes of the European Communities as amended by Regulation (EU) 2015/759 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2015". EUR-Lex. 29 April 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ "PROTOCOL (No 4) of the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union ON THE STATUTE OF THE EUROPEAN SYSTEM OF CENTRAL BANKS AND OF THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK" (PDF). EUR-lex. 7 June 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.