| Maia in hieroglyphs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Era: New Kingdom (1550–1069 BC) | ||||

Maia was the wet nurse of the ancient Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamun in the 14th century BC. Her rock-cut tomb was discovered in the Saqqara necropolis in 1996. [1] [2]

| Maia in hieroglyphs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Era: New Kingdom (1550–1069 BC) | ||||

Maia was the wet nurse of the ancient Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamun in the 14th century BC. Her rock-cut tomb was discovered in the Saqqara necropolis in 1996. [1] [2]

Maia bears the titles "wet nurse of the king", "educator of the god's body" and "great one of the harem". Her origin and relatives are not known. Apart from Tutankhamun, the Overseer of the Magazine Rahotep, the High Priest of Thoth, and scribes named Tetinefer and Ahmose are mentioned in inscriptions. Due to the close resemblance of Maia with Tutankhamun's sister Meritaten, it was suggested that the two are identical. [3]

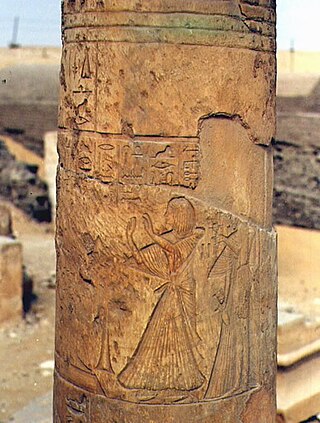

Maia's tomb was discovered in 1996 by the French archaeologist Alain Zivie and his team in the vicinity of the Bubasteion complex dedicated to the deity Bastet at Saqqara. The outside of the tomb is built on limestone with four pillars forming a square. The side walls of the entrance are decorated with colourful and well preserved inscriptions. A relief in the tomb's first chamber shows Maia sitting on a chair with Tutankhamun on her lap and surrounded by six people honouring the young king. On the opposite wall there is a badly damaged scene showing Maia in front of the king. Only three limestone blocks of these scenes are preserved. [4] A door leads to a second longer chamber found full of rubble and partly burnt mummified cats. The second room is dedicated to the burial rites associated with Maia. Maia is shown in front of offering bearers. [5] She is depicted as a mummy in relation to the opening of the mouth ritual and she is standing before the underworld god Osiris. [6] Another door opens to a third chamber, a hall with pillars, also found full of rubble. The pillars are decorated with the image of Maia. The back of the room shows a stela carved into the rock with Maia in front of Osiris. [7] From this hall, a shaft leads to a lower level of the tomb. [1] The tomb's chapel contained a limestone sarcophagus with a cat mummy inside. [2] Masonry work carried out in later periods covered wall paintings in the third chamber and included several pillars into the chamber's walls. Once uncovered, these pillars revealed paintings of Maia. A stela carved out of rock in the back of this room bears reliefs and inscriptions. [8]

In 2001, the team started to explore the tomb's first lower level, which also contained large amounts of cat mummies beside human mummies, votive objects, statues and sarcophagi. This level had also been reused in later periods of the tomb's history. [2] On this level, the skeleton of a male lion was found in autumn 2001. It did not have any bandages, but showed signs of mummification similar to other cat mummies found in the tomb. [9] It had probably lived and died in the Ptolemaic period. [10]

The second lower level was explored in autumn 2002. It is smaller than the previous levels and has not been reused. [2]

In December 2015 the tomb was opened for the public. [11]

Tutankhamun, Tutankhamon or Tutankhamen, also known as Tutankhaten, was the antepenultimate pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt. His death marked the cessation of the dynasty's royal line.

Saqqara, also spelled Sakkara or Saccara in English, is an Egyptian village in the markaz (county) of Badrashin in the Giza Governorate, that contains ancient burial grounds of Egyptian royalty, serving as the necropolis for the ancient Egyptian capital, Memphis. Saqqara contains numerous pyramids, including the Pyramid of Djoser, sometimes referred to as the Step Tomb, and a number of mastaba tombs. Located some 30 km (19 mi) south of modern-day Cairo, Saqqara covers an area of around 7 by 1.5 km.

The tomb of Tutankhamun, also known by its tomb number, KV62, is the burial place of Tutankhamun, a pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt, in the Valley of the Kings. The tomb consists of four chambers and an entrance staircase and corridor. It is smaller and less extensively decorated than other Egyptian royal tombs of its time, and it probably originated as a tomb for a non-royal individual that was adapted for Tutankhamun's use after his premature death. Like other pharaohs, Tutankhamun was buried with a wide variety of funerary objects and personal possessions, such as coffins, furniture, clothing and jewelry, though in the unusually limited space these goods had to be densely packed. Robbers entered the tomb twice in the years immediately following the burial, but Tutankhamun's mummy and most of the burial goods remained intact. The tomb's low position, dug into the floor of the valley, allowed its entrance to be hidden by debris deposited by flooding and tomb construction. Thus, unlike other tombs in the valley, it was not stripped of its valuables during the Third Intermediate Period.

The Barbary lion, also called the North African lion, Atlas lion, and Egyptian lion, is an extinct population of the lion subspecies Panthera leo leo. It lived in the mountains and deserts of the Maghreb of North Africa from Morocco to Egypt. It was eradicated following the spread of firearms and bounties for shooting lions. A comprehensive review of hunting and sighting records revealed that small groups of lions may have survived in Algeria until the early 1960s, and in Morocco until the mid-1960s. Today, it is locally extinct in this region. Fossils of the Barbary lion dating to between 100,000 and 110,000 years were found in the cave of Bizmoune, near Essaouira.

The ancient Egyptians had an elaborate set of funerary practices that they believed were necessary to ensure their immortality after death. These rituals included mummifying the body, casting magic spells, and burials with specific grave goods thought to be needed in the afterlife.

In ancient Egypt, cats were represented in social and religious scenes dating as early as 1980 BC. Several ancient Egyptian deities were depicted and sculptured with cat-like heads such as Mafdet, Bastet and Sekhmet, representing justice, fertility, and power, respectively. The deity Mut was also depicted as a cat and in the company of a cat.

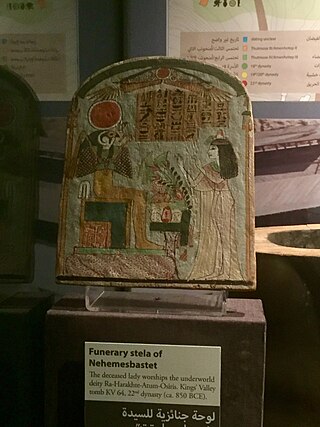

KV64 is the tomb of an unknown Eighteenth Dynasty individual in the Valley of the Kings, near Luxor, Egypt that was re-used in the Twenty-second Dynasty for the burial of the priestess Nehmes Bastet, who held the office of "chantress" at the temple of Karnak. The tomb is located on the pathway to KV34 in the main Valley of the Kings. KV64 was discovered in 2011 and excavated in 2012 by Susanne Bickel and Elina Paulin-Grothe of the University of Basel.

This is a glossary of ancient Egypt artifacts.

Animal mummification was common in ancient Egypt. Animals were an important part of Egyptian culture, not only in their role as food and pets, but also for religious reasons. Many different types of animals were mummified, typically for four main purposes: to allow people's beloved pets to go on to the afterlife, to provide food in the afterlife, to act as offerings to a particular god, and because some were seen as physical manifestations of specific deities that the Egyptians worshipped. Bastet, the cat goddess, is an example of one such deity. In 1888, an Egyptian farmer digging in the sand near Istabl Antar discovered a mass grave of felines, ancient cats that were mummified and buried in pits at great numbers.

Ptahemhat called Ty was High Priest of Ptah in Memphis during the time of 18th Dynasty reign of Tutankhamen and/or Ay.

This page list topics related to ancient Egypt.

The Serapeum of Saqqara was the ancient Egyptian burial place for sacred bulls of the Apis cult at Memphis. It was believed that the bulls were incarnations of the god Ptah, which would become immortal after death as Osiris-Apis. a name which evolved to Serapis (Σέραπις) in the Hellenistic period, and Userhapi (ⲟⲩⲥⲉⲣϩⲁⲡⲓ) in Coptic. It is part of the Saqqara necropolis, which includes several other animal catacombs, notably the burial vaults of the mother cows of the Apis.

Nehmes Bastet or Nehemes-Bastet was an Ancient Egyptian priestess who held the office of "chantress"; she was the daughter of the high priest of Amun. She lived during the Twenty-second Dynasty and was buried in tomb KV64 in the Valley of the Kings. It was excavated in 2012 and discovered to be a reuse of a tomb for the burial of a woman of an earlier dynasty, whose name, as yet, is unknown.

In some European cultures it was customary to place the dried or desiccated body of a cat inside the walls of a newly built home to ward off evil spirits or as a good luck charm. It was believed that the cats had a sixth sense and that putting a cat in the wall was a blood sacrifice so the animal could use psychic abilities to find and ward off unwanted spirits. Although some accounts claim the cats were walled in alive, examination of recovered specimens indicates post-mortem concealment in most cases.

The Department of Egyptian Antiquities of the Louvre is a department of the Louvre that is responsible for artifacts from the Nile civilizations which date from 4,000 BC to the 4th century. The collection, comprising over 50,000 pieces, is among the world's largest, overviews Egyptian life spanning Ancient Egypt, the Middle Kingdom, the New Kingdom, Coptic art, and the Roman, Ptolemaic, and Byzantine periods.

The Tomb of Thutmose is a small, decorated rock-cut tomb in Saqqara in Egypt that dates to the time shortly after the Amarna Period. The tomb is of special importance as one of the tomb owners was the sculptor Thutmose, often presumed to be the person who made the famous Nefertiti Bust. Another of the persons buried here was a certain Kenana.

The Bubasteum or Bubasteion was a Ptolemaic and Roman temple complex dedicated to Bastet in the cliff face of the desert boundary of Saqqara. In Arabic the place is called Abwab el-Qotat.

Tia was an ancient Egyptian high official under king Ramses II. His main title was that of an overseer of the treasuries. Tia was married to a woman with the same name, the princess Tia who was sister of Ramses II.

Mostafa Waziri was the secretary-general of the Supreme Council of Antiquities of Egypt.

The archaeology of Ancient Egypt is the study of the archaeology of Egypt, stretching from prehistory through three millennia of documented history. Egyptian archaeology is one of the branches of Egyptology.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link){{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)