The Aberdeen Bestiary is a 12th-century English illuminated manuscript bestiary that was first listed in 1542 in the inventory of the Old Royal Library at the Palace of Westminster. Due to similarities, it is often considered to be the "sister" manuscript of the Ashmole Bestiary. The connection between the ancient Greek didactic text Physiologus and similar bestiary manuscripts is also often noted. Information about the manuscript's origins and patrons are circumstantial, although the manuscript most likely originated from the 13th century and was owned by a wealthy ecclesiastical patron from north or south England. Currently, the Aberdeen Bestiary resides in the Aberdeen University Library in Scotland.

A bestiary is a compendium of beasts. Originating in the ancient world, bestiaries were made popular in the Middle Ages in illustrated volumes that described various animals and even rocks. The natural history and illustration of each beast was usually accompanied by a moral lesson. This reflected the belief that the world itself was the Word of God and that every living thing had its own special meaning. For example, the pelican, which was believed to tear open its breast to bring its young to life with its own blood, was a living representation of Jesus. Thus the bestiary is also a reference to the symbolic language of animals in Western Christian art and literature.

The Physiologus is a didactic Christian text written or compiled in Greek by an unknown author, in Alexandria; its composition has been traditionally dated to the 2nd century AD by readers who saw parallels with writings of Clement of Alexandria, who is asserted to have known the text, though Alan Scott has made a case for a date at the end of the 3rd or in the 4th century. The Physiologus consists of descriptions of animals, birds, and fantastic creatures, sometimes stones and plants, provided with moral content. Each animal is described, and an anecdote follows, from which the moral and symbolic qualities of the animal are derived. Manuscripts are often, but not always, given illustrations, often lavish.

The unicorn is a legendary creature that has been described since antiquity as a beast with a single large, pointed, spiraling horn projecting from its forehead.

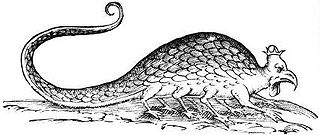

A cockatrice is a mythical beast, essentially a two-legged dragon or serpent-like creature with a rooster's head. Described by Laurence Breiner as "an ornament in the drama and poetry of the Elizabethans", it was featured prominently in English thought and myth for centuries.

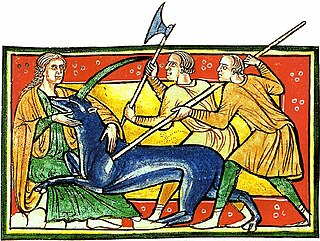

The bonnacon is a legendary creature described as a bull with inward-curving horns and a horse-like mane. Medieval bestiaries usually depict its fur as reddish-brown or black. Because its horns were useless for self-defense, the bonnacon was said to expel large amounts of caustic feces from its anus at its pursuers, burning them and thereby ensuring its escape.

The crocotta or corocotta, crocuta, or leucrocotta is a mythical dog-wolf of India or Aethiopia, linked to the hyena and said to be a deadly enemy of men and dogs.

The four senses of Scripture are a four-level method of interpreting the Bible. This method originated in Christianity and was taken up in Judaism by the Kabbalah.

The salamander is an amphibian of the order Urodela which, as with many real creatures, often has been ascribed fantastic and sometimes occult qualities by pre-modern authors not possessed by the real organism. The legendary salamander is often depicted as a typical salamander in shape with a lizard-like form, but is usually ascribed an affinity with fire, sometimes specifically elemental fire.

Benoît de Maillet was a well-travelled French diplomat and natural historian. He was French consul general at Cairo, and overseer in the Levant. He formulated an evolutionary hypothesis to explain the origin of the earth and its contents.

According to the tradition of the Physiologus and medieval bestiaries, the aspidochelone is a fabled sea creature, variously described as a large whale or vast sea turtle, and a giant sea monster with huge spines on the ridge of its back. No matter what form it is, it is always described as being huge where it is often mistaken for an island and appears to be rocky with crevices and valleys with trees and greenery and having sand dunes all over it. The name aspidochelone appears to be a compound word combining Greek aspis, and chelone, the turtle. It rises to the surface from the depths of the sea, and entices unwitting sailors with its island appearance to make landfall on its huge shell and then the whale is able to pull them under the ocean, ship and all the people, drowning them. It also emits a sweet smell that lures fish into its trap where it then devours them. In the moralistic allegory of the Physiologus and bestiary tradition, the aspidochelone represents Satan, who deceives those whom he seeks to devour.

A pard is the Greek word for the leopard, which is listed in Medieval bestiaries and in Pliny the Elder's book Natural History. Over the years, there have been many different depictions of the creature including some adaptations with and without manes and some in later years with shorter tails. However, one consistent representation shows them as large felines often with spots.

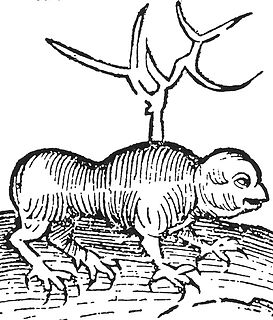

The Myrmecoleon or Ant-lion is a fantastical animal from classical times, possibly derived from an error in the Septuagint version of the book of Job, reappearing in the Greek Christian Physiologus of the 3rd or 4th century A.D.

In European bestiaries and legends, a basilisk is a legendary reptile reputed to be a serpent king, who can cause death with a single glance. According to the Naturalis Historia of Pliny the Elder, the basilisk of Cyrene is a small snake, "being not more than twelve fingers in length", that is so venomous, it leaves a wide trail of deadly venom in its wake, and its gaze is likewise lethal.

A legendary creature is a supernatural animal or paranormal entity, generally a hybrid, sometimes part human, whose existence has not or cannot be proven and that is described in folklore, but also may be featured in historical accounts before modernity.

"Fastitocalon" is a medieval-style poem by J. R. R. Tolkien about a gigantic sea turtle. The setting is explicitly Middle-earth. The poem is included in The Adventures of Tom Bombadil.

The Rochester Bestiary is a richly illuminated manuscript copy of a medieval bestiary, a book describing the appearance and habits of a large number of familiar and exotic animals, both real and legendary. The animals' characteristics are frequently allegorised, with the addition of a Christian moral.

The Worksop Bestiary, also known as the Morgan Bestiary, most likely from Lincoln or York, England, is an illuminated manuscript created around 1185, containing a bestiary and other compiled medieval Latin texts on natural history. The manuscript has influenced many other bestiaries throughout the medieval world and is possibly part of the same group as the Aberdeen Bestiary, Alnwick Bestiary, St.Petersburg Bestiary, and other similar Bestiaries. Now residing in the Morgan Library & Museum in New York, the manuscript has had a long history of church, royal, government, and scholarly ownership.

The Icelandic Physiologus is a translation of the 2nd Century Greek Physiologus, adapted from a later Latin version. It survives in fragmentary form in two manuscripts, both dating from ca. 1200 making them some of the earliest Icelandic manuscripts, and the earliest illustrated manuscripts from Iceland. The fragments are significantly different from each other and either represent copies from two separate exemplars or different reworkings of the same text. Both texts also contain material that is not found in standard versions of the Physiologus.

One version of the myth about the barnacle and brant geese is that these geese emerge fully-formed from goose barnacles (Cirripedia). There are other myths about how the barnacle goose breeds. The basis of all the myths is that the bird, Branta leucopsis, emerges and grows from matter other than bird eggs. There are many sources to the myth. The etymology of the term "barnacle" suggests Latin, Old English and French roots. There are few references in pre-Christian books and manuscripts – some Roman or Greek. The main vector for the myth into modern times was monastic manuscripts and in particular the Bestiary. The myth owes its long standing popularity to an early ignorance of the migration patterns of geese. Early medieval discussions of the nature of living organisms were often based on myths or genuine ignorance of what is now known about phenomena such as bird migration. It was not until the late 19th century that bird migration research showed that such geese migrate northwards to nest and breed in Greenland or northern Scandinavia.