A mining accident is an accident that occurs during the process of mining minerals or metals. Thousands of miners die from mining accidents each year, especially from underground coal mining, although accidents also occur in hard rock mining. Coal mining is considered much more hazardous than hard rock mining due to flat-lying rock strata, generally incompetent rock, the presence of methane gas, and coal dust. Most of the deaths these days occur in developing countries, and rural parts of developed countries where safety measures are not practiced as fully. A mining disaster is an incident where there are five or more fatalities.

The Oaks explosion, which happened at a coal mine in West Riding of Yorkshire on 12 December 1866, remains the worst mining disaster in England. A series of explosions caused by firedamp ripped through the underground workings at the Oaks Colliery at Hoyle Mill near Stairfoot in Barnsley killing 361 miners and rescuers. It was the worst mining disaster in the United Kingdom until the 1913 Senghenydd explosion in Wales.

Clifton Hall Colliery was one of two coal mines in Clifton on the Manchester Coalfield, historically in Lancashire which was incorporated into the City of Salford in Greater Manchester, England in 1974. Clifton Hall was notorious for an explosion in 1885 which killed around 178 men and boys.

A man engine is a mechanism of reciprocating ladders and stationary platforms installed in mines to assist the miners' journeys to and from the working levels. It was invented in Germany in the 19th century and was a prominent feature of tin and copper mines in Cornwall until the beginning of the twentieth century.

Stratton's Independence Mine and Mill is a historic gold mining site near Victor, Colorado on the south slope of Battle Mountain. Between late 1893 and April 1899, approximately 200,000 ounces (6200 kg) of gold was removed from the Independence Mine.

Elandsrand is a small mining town approximately 10 km (6 mi) outside Carletonville next to Blyvooruitzicht.

The Elsecar Collieries were the coal mines sunk in and around Elsecar, a small village to the south of Barnsley in what is now South Yorkshire, but was traditionally in the West Riding of Yorkshire.

Ladyshore Colliery, originally named Back o' th Barn, was situated on the Irwell Valley fault on the Manchester Coalfield in Little Lever, then in the historic county of Lancashire, England. Founded by Thomas Fletcher Senior, the colliery opened in the 1830s and mined several types of coal. It became infamous as a result of the owners' stand against the use of safety lamps in the mines. Women and children worked in the mines, under poor conditions.

Pleasley Colliery is a former English coal mine. It is located to the north-west of Pleasley village, which sits above the north bank of the River Meden on the Nottinghamshire/Derbyshire border. It lies 3 miles (4.8 km) north of Mansfield and 9 miles (14.5 km) south of Chesterfield. From the south it commands a prominent position on the skyline, although less so now than when the winders were in operation and both chimney stacks were in place. The colliery is situated at about 500 ft (152m) above sea level and is aligned on a NE–SW axis following the trend of the river valley at this point.

Chatterley Whitfield Colliery is a disused coal mine on the outskirts of Chell, Staffordshire in Stoke on Trent, England. It was the largest mine working the North Staffordshire Coalfield and was the first colliery in the UK to produce one million tons of saleable coal in a year.

Edward Ormerod was an English mining engineer.

Bradford Colliery was a coal mine in Bradford, Manchester, England. Although part of the Manchester Coalfield, the seams of the Bradford Coalfield correspond more closely to those of the Oldham Coalfield. The Bradford Coalfield is crossed by a number of fault lines, principally the Bradford Fault, which was reactivated by mining activity in the mid-1960s.

The Gleision Colliery mining accident was a mining accident which occurred on 15 September 2011 at the Gleision Colliery, a drift mine at Cilybebyll in Neath Port Talbot, in Wales. The accident occurred while seven miners were working with explosives on a narrow coal seam. Following a blasting operation into a separate disused flooded mine network to increase air-circulation, the tunnel in which the miners were working began to fill with water. Three of the miners escaped, with one being taken to hospital with life-threatening injuries, while the others were trapped underground. A search and rescue operation was launched to locate the four remaining miners, but they were found deceased the following day. The incident is the worst mining disaster to occur in Wales for three decades.

The Racecourse Colliery is an exhibit located at the Black Country Living Museum.

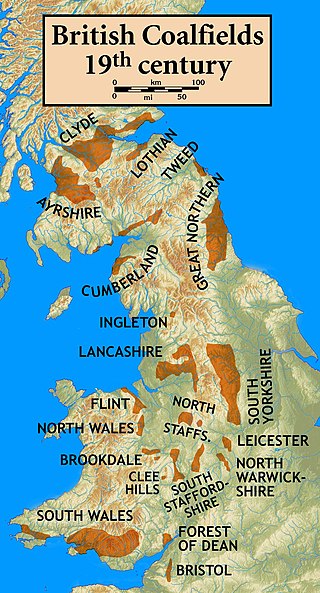

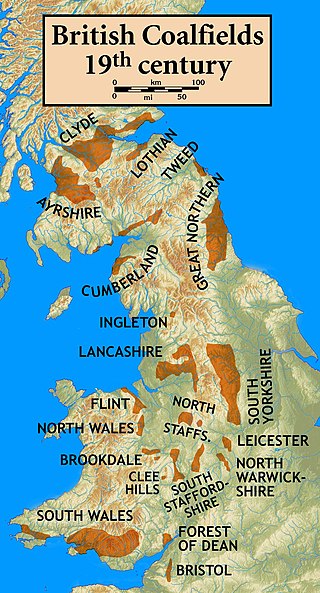

This is a partial glossary of coal mining terminology commonly used in the coalfields of the United Kingdom. Some words were in use throughout the coalfields, some are historic and some are local to the different British coalfields.

The Peckfield pit disaster was a mining accident at the Peckfield Colliery in Micklefield, West Yorkshire, England, which occurred on Thursday 30 April 1896, killing 63 men and boys out of 105 who were in the pit, plus 19 out of 23 pit ponies.

The Coal Mines Act 1911 amended and consolidated legislation in the United Kingdom related to collieries. A series of mine disasters in the 19th and early-20th centuries had led to commissions of enquiry and legislation to improve mining safety. The 1911 Act, sponsored by Winston Churchill, was passed by the Liberal government of H. H. Asquith. It built on earlier regulations and provided for many improvement to safety and other aspects of the coal mining industry. An important aspect was that mine owners were required to ensure there were mines rescue stations near each colliery with equipped and trained staff. Although amended several times, it was the main legislation governing coal mining for many years.

The Lundhill Colliery explosion was a coal mining accident which took place on 19 February 1857 in Wombwell, Yorkshire, UK in which 189 men and boys aged between 10 and 59 died. It is one of the biggest industrial disasters in the country's history and it was caused by a firedamp explosion. It was the first disaster to appear on the front page of the Illustrated London News.

Barrow Colliery was a coal mine in Worsborough, South Yorkshire, England. It was first dug in 1873, with the first coal being brought to the surface in January 1876. It was the scene of a major incident in 1907 when seven miners died. After 109 years of coaling operations, the mine was closed in May 1985.

Richmond Main Colliery is a heritage-listed former coal mine and now open-air museum at South Maitland Coalfields, Kurri Kurri, New South Wales, Australia. It was designed by the staff at J & A Brown's Engineering Workshops at Hexham under the direction of John Brown and built from 1908 to 1913 by J & A Brown. The site now operates as the Richmond Main Heritage Park, including the Richmond Vale Railway Museum and Richmond Main Mining Museum. The property is owned by Cessnock City Council. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.